Undeclared North Korea: The Sangnam-ni Missile Operating Base

Key Findings

- Located 250 kilometers north of the DMZ, Sangnam-ni (상남리) missile operating base is an operational missile base that houses a battalion- or regiment-sized unit equipped with Hwasong-10 (Musudan) intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBM).1

- The deployment of the Hwasong-10, with 3000+ kilometer ranges, at Sangnam-ni is a component of North Korea’s presumed offensive ballistic missile strategy that provides a strategic-level first strike capability against targets located throughout East Asia as far as U.S. forces in Okinawa and Guam.

- The base is defended against by a single anti-aircraft artillery position and nearby surface-to-air missile bases.

- Repeated flight failures of the Hwasong-10 may lead to the Strategic Force’s replacing it with the successful Hwasong-12 IRBM (KN-17) or Pukkuksong-2 (KN-15) medium-range-ballistic missiles (MRBM). The Hwasong-12 has a flight range up to 4,500km and the Pukkuksong-2 has an operational flight range estimated at between 1,200km-2,000+ km.

- Sangnam-ni is one of approximately 20 North Korean ballistic missile operating bases that has never been declared by North Korea. The base does not appear to be the subject of denuclearization negotiations between the United States and North Korea.

- Some have argued that North Korea is under no obligation to declare these operational missiles bases. But ten standing United Nations Security Council Resolutions, including the most recent UNSCR 2397, explicitly ban North Korea from developing and testing ballistic missiles.2

- Any potential agreement that decommissions the Tongchang-ri (Sohae) rocket test stand alone would obscure the extant military threat to U.S. forces and South Korea from this and other undeclared ballistic missile bases in this CSIS study.

Sangnam-ni Missile Operating Base

The Sangnam-ni (상남리) missile operating base (40.838977 128.541650) is located within North Korea’s strategic missile belt in Hochon-gun (Hochon County), Hamgyong-namdo (South Hamgyong Province). It sits 310 kilometers northeast of Pyongyang, 250 kilometers north of the demilitarized zone, 390 kilometers northeast of Seoul and 1,130 northwest of Tokyo.3

Disambiguation of references to a reported missile base in Hochon-gun are actually referring to the Sangnam-ni missile operating base. Likewise, references to a missile base at Pochi-ri (포치리) in either Hochon-gun (40.742778, 128.501944) 11 km to the southwest or Pungso-gun, Ryanggang Province, (41.010556, 128.220833) 33 km to the northwest are likely also referring to Sangnam-ni.

Subordinate to the KPA’s Strategic Force (the organization responsible for all ballistic missile units), the Sangnam-ni missile operating base houses a battalion- or regiment-sized unit equipped with Hwasong-10 (Musudan) intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBM).4 This unit, with its 3,000+ kilometers range Hwasong-10’s, represents an important component of North Korea’s presumed offensive ballistic missile strategy by providing a strategic-level first strike capability against targets throughout East Asia including the major U.S. bases on Okinawa and potentially Guam.

Until more is known, however, this capability should be characterized as “theoretical” as the Hwasong-10 was deployed to operational units without testing in an “emergency launch capability” mode during the early 2000s.5 Later, in 2016, when KPA units conducted a number of training launches with the system it suffered repeated catastrophic failures.6 These repeated launch/flight failures appear to have resulted in no new launches of the Hwasong-10 since that time. This, in turn, may lead to the Strategic Force’s abandoning the system and replacing it with the more successful Hwasong-12 IRBM or Pukkuksong-2 (KN-15) MRBM. 7 The production status of these newer systems is, however, unknown.

Development

Unlike the Sakkanmol or Sino-ri missile operating bases, reliable open source information concerning the development and operations of the Sangnam-ni base is scarce. What is known is that during the late 1980s and early 1990s, in addition to its construction of forward Hwasong-5/-6 missile operating bases north of the DMZ, North Korea developed plans for the construction of a series of strategic ballistic missile operating bases in the northern sections of the country for longer range systems under development.

One of the first known public reports concerning these new ballistic missile operating bases became available in March 1999 when a senior South Korean official told reporters of bases being built at Sangnam-ni, Yongjo-ri (영저리) and Yongnim-up (영림읍).8 At that time there were no indications of the types of missiles that were to be deployed at these new bases, however, reports later that year stated that these were “suspected to be Nodong-1 or Taepodong-1 and -2 bases.”9

Construction of the Sangnam-ni missile operating base began sometime during 1994 using specialized engineering troops from the KPA’s Military Construction Bureau.10 The location selected for the base was one kilometer south of the town of Sangnam-ni on the south side of the Namdae-chon (남대천, Namdae stream). Specifically, in an isolated bifurcated mountain valley containing minor streams on the northern slopes of Huisa-bong (희사봉, Huisa Mountain). At this time only minor agricultural activity, around the tiny hamlet of Togyongdong-ni (덕용리), and minor scattered logging operations were present in the area.

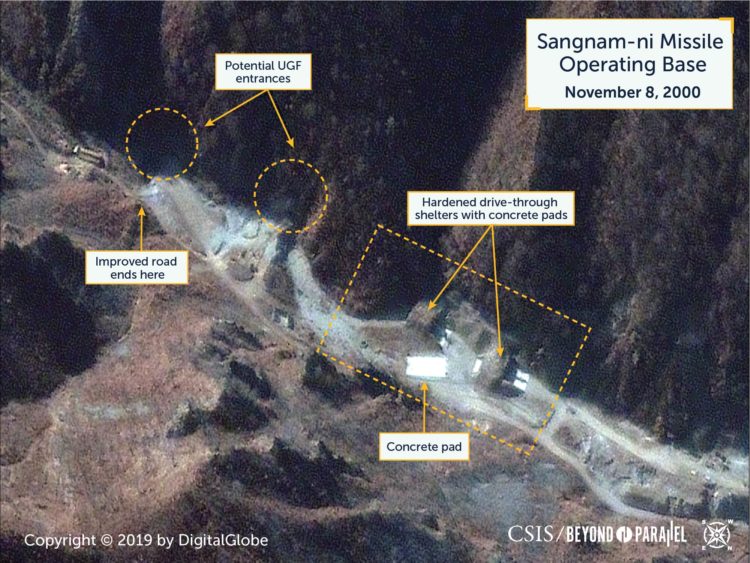

Although no open source high-resolution satellite imagery from the mid-1990s is presently available, construction is reliably reported to have proceeded slowly and was initially focused upon road construction, construction of a hardened drive-through facility and the excavation of what is believed to be an underground facility (UGF) approximately 2.6 km up from the base of the valley.11 Satellite imagery from August 2000 indicates that at this time two new roads had been built into both sides of the southern valley—with the longest being 2.8-kilometers-long.

Additionally, major excavation of the potential UGF was likely complete—but may have been continuing internally—as imagery analysis revealed there were no external indications of excavation activity or equipment at the time. Construction of the hardened drive-through facility was also complete and a small number of barracks (likely for worker housing) and support structures was ongoing. Although no large buildings were under construction at this time, initial grading had begun at the intersection of the main and branch valleys where the headquarters would be located. No activity of significance was noted at the village of Togyongdong-ni (40.839840 128.551308), up the branch valley to the east.

Reports from mid-2001 state that the base was “…60-80 percent complete in the construction phase.”12 Analysis of a December 2002 satellite image supports these reports showing a number of significant changes since 2000. At the base of the valley, in the support and headquarters area, an entrance/security checkpoint had been established and minor agricultural support activity was present. In addition, approximately seven new structures were built just east of the entrance, and the grading in the headquarters area was completed and a headquarters/administration building was erected. The road south had now been extended far past the hardened drive-through facility and over the northern slopes of Huisa-bong (Huisa Mountain) by means of a series of large switchbacks.

The support area along the east side of the road had been expanded significantly with at least thirteen structures (e.g., barracks, warehouses, vehicle maintenance, etc.) now present. A new building was also constructed on the side of the road at the southern entrance to the base that appears to be a security checkpoint and barracks. No significant changes were noted in the area of the hardened drive-through facility. At the village of Togyongdong-ni some initial grading and several new structures were noted. Agricultural support appears to have been slightly expanded and a small bridge on the road leading to the village was under construction in the headquarters area.

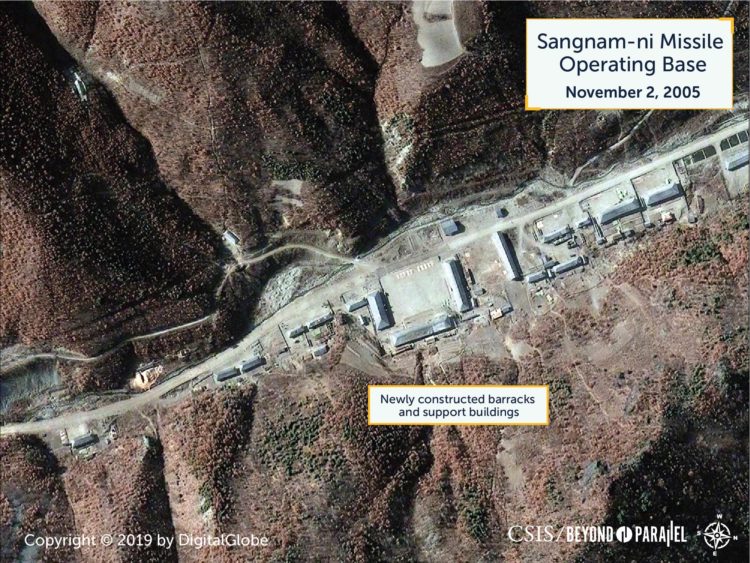

During May 2004 new reports stated that the base was now “…70 to 80 percent completed…”13 Satellite imagery from November of that year tends to support these reports. In the barracks and support area just east of the entrance, a number of new barracks or support buildings had been built. In the headquarters area three additional structures were built and the small bridge on the road leading to Togyongdong-ni was now complete. In the support area along the road south there were continuing changes among the structures, however, the overall number remained relatively constant. Again, no significant changes were noted in the area of the hardened drive-through facility. Along the branch valley east of the headquarters several new structures were built and minor grading continued in the village of Togyongdong-ni.

By 2004, reports had also begun to surface that Sangnam-ni, Yongjo-ri and Yongnim-up were being equipped with a “new IRBM” and were “not Scud and Nodong-1 bases.”14 Shortly afterwards it was confirmed that Sangnam-ni was a missile operating base that housed a battalion- or regiment-sized unit equipped of the KPA’s recently established Hwasong-10 (Musudan) IRBM brigade.15

It is unclear whether the Sangnam-ni unit participated in the large 2004 Command Post Exercise (CPX) for ballistic missile units, however, from 2006 onwards it is reported to have regularly participated in the annual training cycle.16

During 2005, minor construction was observed throughout the facility and a new road was built from the barracks, warehouse, and support area 500 meters up the ridge to the west where a new anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) battery position was established. The bridge leading to Togyongdong-ni in the headquarters had been finished and work on improving the road to the village was underway.

While a report from August 2006 states that the “…construction of a base in Sangnam-ri is 70 to 80 percent completed” satellite imagery from 2005-2008 suggests that it is likely that the initial phase of construction at the base was essentially complete by the end of 2006.17

During 2009-2010, a small second phase of construction was undertaken that witnessed an expansion of the headquarters area with the construction of two administration buildings. Aside from these buildings only minor construction activity (e.g., erection of a memorial, removal and construction of small structures) and minimal increases of agricultural support activities were observed in satellite imagery from 2006-2012.

Subsequently, during 2013-2015, the existing cultural/education hall within the headquarters area was razed and a new larger hall was built, two new monuments were erected on the east side of the headquarters area, a small orchard was planted, and a greenhouse was built.

Analysis of satellite imagery from 2015 until present shows only minor infrastructure changes to the base that are consistent with what is often observed at remote KPA bases of all types.

As of December 2018, the base is active and being well-maintained by North Korean standards.

Organization

Encompassing approximately 3.85 square kilometers, the primary section of Sangnam-ni missile operating base extends 2.9 kilometers up the primary branch valley running southeast and then south on the northern slopes of Huisa-bong (Huisa Mountain). A small secondary branch extends off this valley to the east and the village of Togyongdong-ni that provides agricultural and other support. Most of the area encompassed by the base consists of unoccupied mountains and small agricultural activities that support the base. The small hamlet at the base of the valley, and outside the entrance, does not appear to be directly associated with the base.

The base can be functionally divided into four activities—agricultural support (including a greenhouse, small orchards and small terraced fields), main base (including headquarters, barracks, vehicle maintenance, storage, and a variety of small support elements), missile support, and potential underground facilities.18

As with a number of other KPA missile operating bases located in remote mountainous areas the Sangnam-ni headquarters area is located at the intersection of the eastern and southern branches of the valley. This area consists of the headquarters, cultural/education hall, approximately a dozen small barracks and support buildings, greenhouse, small orchard and a parade ground. There is also a lesser valley that branches off to the east from the headquarters area to the small village of Togyongdong-ni. This village appears to provide agricultural and other minor support to the base. Extending approximately 750 meters south and up the valley from the headquarters area are a number of barracks, warehouses and support structures.

Above this area, on a ridge 500 meters to the west, is a light AAA battery position equipped with eight guns. This battery is likely organic to the base as the only access road to it originates at the support area.

Located approximately 1.4 km up the valley from the headquarters area is the base’s missile support facility—used for arming, fueling, systems checkout, and maintenance operations. It consists of a hardened drive-through facility measuring approximately 130-meters-by-40-meters overall with two approximately 20-meter-long earth-covered shelters separated by an open bay. Each shelter has an approximately 40-meter-by-15-meter concrete pad running through it. A third approximately 30-meter-by-15-meter concrete pad is on the road side and between the two shelters. The intended purpose of this third concrete pad is unknown, however, it is large enough to support a missile launch under emergency conditions—KPA tactics and doctrine is believed to call for ballistic missile TELs/MELs to disperse from their bases during wartime launch operations.

Cut into the mountain slope on the north side of each shelter is an approximately 9-meter-by-6-meter opening that is likely an entrance to an underground storeroom or small UGF. If a UGF, it is likely that the two entrances are internally connected. While sufficient for some trucks and support vehicles to enter, these entrances appear to be too small to be useable by known Hwasong-10 transporter-erector-launcher (TEL) or mobile-erector-launchers (MEL).

A further 150 meters up the valley is what appears to be the first of two potential UGF entrances. The second potential entrance is a further 100 meters up the valley. Positive confirmation of these entrances is elusive due to the resolution of available imagery and the entrances being cut into a steep western mountain face that is often in shadow. Exploratory measurements suggest that the entrances are at between 10- and 13-meters-wide and large enough to handle any of the missile unit’s TEL/MELs and support vehicles. It is uncertain whether the UGF entrances are internally connected so that vehicles can drive through them. At a minimum, per typical KPA practice, they are linked by small internally connected tunnels. Unlike at other missile operating bases there are no large rock and dirt berms in front of the entrances. This is likely due to the narrowness of the valley at this point, which provides some measure of protection from artillery fire and aerial attack.

Due to the fact that the hardened drive-through facility and potential UGF entrances are embedded into the western slope of a narrow tree-lined valley they are frequently hidden from sight in satellite imagery during spring and summer. These structures are just visible during fall and visible in winter after a snow fall—typically when viewed looking west.

Approximately 175 meters higher up the valley is a single building that is likely a guard barracks and secures the facility from the south. The dirt road that runs south past this barracks continues over the eastern and southern slopes of Huisa Mountain and terminates in the Pochi-ri area 10 kilometers south of the base. This road is of sufficient quality and design (e.g., wide turns, switchbacks, etc.) to allow missile TELs/MELs to use it during wartime.

Potentially, there are additional facilities and UGFs within Hochon-gun (Hochon County) that are either directly associated with the missile unit at Sangnam-ni or tasked to support its operations during wartime.19 No such facilities, however, have been identified in open source reporting.

Detailed organizational information for the KPA ballistic missile unit at the Sangnam-ni missile operating base, other than being part of the Strategic Force’s Hwasong-10 brigade, is essentially nonexistent. From the nature and size of the infrastructure observed in satellite imagery it is likely that it is a battalion- or regiment-sized unit consisting of a headquarters, small service elements and several firing batteries. The number of Hwasong-10 TELs/MELs in the unit is unknown but postulated to be between 2-6.

Despite the strategic importance of all the KPA’s ballistic missile operating bases and concerns of either pre-emptive or wartime airstrikes against these facilities, and aside from the base’s organic AAA battery, there is only a single additional fixed anti-aircraft artillery position within 10 km of the Sangnam-ni base. It is likely that in addition to the organic AAA battery, the missile unit itself possesses organic air defense elements equipped with both light AAA and shoulder fired SAMs (e.g., SA-7, SA-14, SA-16, etc.). The base is within the air defense umbrella of only a single SA-2 and potentially one SA-5 surface-to-air missile (SAM) bases. The Hwangsuwon-ni Airbase is, however, only 36 kilometers to the southwest.

Research Notes

This report, as are the others in this series, is based upon an ongoing study of the Korean People’s Army ballistic missile infrastructure begun by one of the authors, Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., in 1985. This study is in turn based upon numerous interviews with North Korean defectors, declassified documents, open source reporting, and government, defense, and intelligence officials around the world. Accuracy in any discussion of North Korea’s nuclear, biological, chemical, or ballistic missile programs is always a challenge and while some of the information used in the preparation of this study may eventually prove to be incomplete, or incorrect, it is hoped that it provides a new and unique look into the subject. The information presented here supersedes or updates previous works by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. on these subjects.

Although sixteen high-resolution satellite images were analyzed during the preparation of this report, the winter and spring satellite images ultimately presented in this report were purposely selected for their absence of foliage, which allows for a more unobstructed and detailed view of the structures and activities within and around the Sangnam-ni missile operating base.

References

- The authors wish to thank Sang Jun Lee, research associate in the CSIS Korea Chair, Dana Kim, intern in the Korea Chair and the Dracopoulous iDeas Lab, and Young-Kyung Kim, intern in the Korea Chair, for their invaluable research in support of this project. ↩

- This includes the following ten United Nations Security Council Resolutions (UNSCRs): 2397, 2375, 2371, 2356, 2321, 2270, 2094, 2087, 1874, and 1718. One additional UNSCR, 1695, requires North Korea to “suspend all activities related to its ballistic missile programme” and re-establish a moratorium on missile testing. United Nations Security Council, UN Documents for DPRK (North Korea), https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/un-documents/dprk-north-korea/. ↩

- Author interview data; Son Hyo-joo, “Government: Remained Silent so North Korea would not notice surveillance,” Dong-a Ilbo, November 15, 2018, http://news.donga.com/3/all/20181115/92877807/1; “Where are the North Korean “undeclared bases” confirmed by CSIS?,” The Korea Herald, November 13, 2018, http://news.heraldcorp.com/view.php?ud=20181113000879; Jung Chung-sin, “ROK-US Joint Military Exercises, Defense Changes to Preemptive Strikes,” Munhwa Ilbo, March 7, 2016, http://www.munhwa.com/news/view.html?no=2016030701070630114001; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “North Korea’s Ballistic Missile Arsenal is Diversified and Robust,” World Politics Review, March 11, 2014, http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/trend-lines/13622/global-insider-north-korea-s-ballistic-missile-arsenal-is-diversified-and-robust; An Du-won, Kim Min-suh, and Park Byung-jin, “North Korea, another show of missile power? … is it for talks or for use in combat,” Segye Ilbo, April 5, 2013, http://www.segye.com/newsView/20130404004770; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., North Korea’s Ballistic Missile Threat, paper presented at the ASAN Institute For Policy Studies, Nuclear Crisis in Asia, Seoul, October 31-November 1, 2011; Kim Kui-gun, “Kim Guk-bang, Inspects Missile Unit Capable of Striking Entirety of North Korea,” Yonhap News, March 8, 2012, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=001&aid=0005545734; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Behind the Lines—North Korea’s Ballistic Missile Units,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, July 2011, pp. 48-53; An Yong-hyun and Lee Yong-su, “Kim Jong-Un Inspects KPA Celebration with new missile reveal … Formalization of Kim Jong-un’s military acquisition,” Chosun Ilbo, October 11, 2010, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2010/10/11/2010101100037.html; Lee Ki-ju, “Domestic Cruise Missile with 1500 km Range Deployed,” Seoul Economic Daily, July 18, 2010, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=011&aid=0002081759; Daniel A. Pinkston, The North Korean Ballistic Missile Program, (Carlisle Barracks: Strategic Studies Institute), February 2008, pp. 50 and 80; Yu Kang-mun, “Activity of North Korea’s Missile Launch Preparations,” Hankyoreh, September 24, 2004, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=028&aid=0000079504; Kim Kui-gun, “No Sign of North Korean Missile Buildup,” Yonhap News, March 2, 2001, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=102&oid=001&aid=0000057623; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., Shield of the Great Leader: The Armed Forces of North Korea, (London: I.B. Taurus), 2001, pp. 283-291; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “North Korea’s Long-Range Missiles,” in Sheppard, Ben (Ed.), Ballistic Missile Proliferation, (London: Jane’s Information Group), 2000; and Lee Yong-jong, “ROK-US Intelligence: North Korea Has Not Halted Missile Exports,” Joongang Ilbo, March 29, 1999, https://news.joins.com/article/3765186.

The national designator for the missile operating base at Sangnam-ni is unknown and North Korea is not known to have ever made specific reference to its existence.

The transliteration of Korean place names into English is frequently challenging and often results in confusion and the Sangnam-ni missile operating base is no exception to this phenomenon. Among the alternative transliterations for Sangnam-ni are: Sangnam, Sangnam-ri and Sangam-ri. For consistency and ease of reading Sangnam-ni and other places names used in this report are those accepted by the U.S. National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA).

For a description of the North Korean missile belts see: Joseph Bermudez, Victor Cha and Lisa Collins, “Undeclared North Korea: Missile Operating Bases Revealed,” Beyond Parallel, November 12, 2018, https://beyondparallel.csis.org/north-koreas-undeclared-missile-operating-bases/. ↩ - There is considerable confusion concerning the domestic and foreign designations of North Korea’s ballistic missile systems in the open source literature. One of the more comprehensive reviews of these designations, and the one adhered to here is: Scott LaFoy, “The Hwasong that Never Ends,” Arms Control Wonk, August 28, 2017, http://www.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/1203797/the-hwasong-that-never-ends/. ↩

- Author interview data; National Air and Space Intelligence Center, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: National Air and Space Intelligence Center), NASIC-1031-0985-17, June 2017, p. 17; National Air and Space Intelligence Center, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: National Air and Space Intelligence Center), NASIC-1031-0985-13, July 2013, p. 19; An Du-won, Kim Min-suh and Park Byung-jin, “North Korea, another show of missile power? … is it for talks or for use in combat,” Segye Ilbo, April 5, 2013, http://www.segye.com/newsView/20130404004770; Kim Min-suk, “North Korea Creates a Missile Division for New Missile Capable of Reaching Guam U.S. Military Base,” Joongang Ilbo, March 10, 2010, https://news.joins.com/article/4052989; National Air and Space Intelligence Center, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: National Air and Space Intelligence Center), NASIC-1031-0985-09, April 2009, p. 17; Yu Yong-won, “North Korea Deploys Missile That Can Reach Guam,” Chosun Ilbo, February 24, 2009, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2009/02/24/2009022400059.html; and National Air and Space Intelligence Center, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: National Air and Space Intelligence Center), NASIC-1031-0985-06, March 2006, p. 10. ↩

- Anna Fifield, “Did North Korea Just Test Missiles Capable of Hitting the U.S.? Maybe,” Washington Post, October 26, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/did-north-korea-just-test-missiles-capable-of-hitting-the-us-maybe/2016/10/26/984e8a21-e6a7-4689-81e0-21d7d25c302f_story.html?utm_term=.3e46c01be622; “North Korean Missile Reportedly Explodes Soon After Liftoff,” Wall Street Journal, October 16, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-detects-failed-north-korean-missile-launch-1476572239; Anna Fifield, “North Korea’s missile launch has failed, South’s military says,” Washington Post, April 15, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/north-koreas-missile-has-failed-officials-from-south-say/2016/04/14/8eb2ce53-bc38-40d0-9013-5655bed26764_story.html?utm_term=.e216605153b6; and Michael S. Schmidt and Choe Sang-Hun, “North Korea Ballistic Missile Launch a Failure, Pentagon Says,” New York Times, April 15, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/15/world/asia/north-korea-ballistic-missile-launch-a-failure-pentagon-says.html. ↩

- Ibid.; Son Hyo-joo, “Government: Remained Silent so North Korea would not notice surveillance…Preparations for emergency attack completed,” Dong-a Ilbo, November 15, 2018, http://news.donga.com/3/all/20181115/92877807/1; Kim Tae-hoon, “North Korean Sakkanmol Base Controversy … What are their Intentions?” SBS News, November 14, 2018, https://news.sbs.co.kr/news/endPage.do?news_id=N1005015568&plink=ORI&cooper=NAVER; Nam Min-woo, “CNN: North Korea continues to expand its unidentified long-range missile base,” Chosun Ilbo, December 6, 2018, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/12/06/2018120600526.html; Kang Hye-ran and Lee Chul-jae, “CNN: North Korea is Constructing a New Long-range Missile Base after Summit Talks,” Joongang Ilbo, December 7, 2018, https://news.joins.com/article/23188194; Bill Gertz, “Commence Countdown to Launch,” Washington Free Beacon, February 21, 2013; “Press Gets 1st Look at N. Korean Mid-range Missile,” Chosun Ilbo, October 11, 2010, http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2010/10/11/2010101101060.html; An Yong-hyun and Lee Yong-su, “Kim Jong-Un Inspects KPA Celebration with new missile reveal … Formalization of Kim Jong-un’s military acquisition,” Chosun Ilbo, October 11, 2010, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2010/10/11/2010101100037.html; Kim Min-suk, “North Korea Creates a Missile Division for New Missile Capable of Reaching Guam U.S. Military Base,” Joongang Ilbo, March 10, 2010, https://news.joins.com/article/4052989; Yu Yong-won, “North Korea Deploys Missile That Can Reach Guam,” Chosun Ilbo, February 24, 2009, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2009/02/24/2009022400059.html; and Steven A. Hildreth, North Korean Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States, (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service), RS21473, January 28, 2009, p. 4. ↩

- Lee Yong-jong, “ROK-US Intelligence: North Korea Has Not Halted Missile Exports,” Joongang Ilbo, March 29, 1999, https://news.joins.com/article/3765186. ↩

- Yu Yong-won, “North Korea Continues Secret Missile Buildup Efforts Including Construction of 3 Underground Facilities in Rear,” Chosun Ilbo, March 2, 2001, http://news.chosun.com/svc/content_view/content_view.html?contid=2001030270034; Yu Yong-won, “DPRK Deploys 100 Nodong-1 Missiles,” Chosun Ilbo, March 2, 2001, http://news.chosun.com/svc/content_view/content_view.html?contid=2001030270035; “Army Denies Report on N.K.’s Alleged Missile Deployment,” Yonhap News, March 2, 2001; Kim Kui-gun, “No Sign of North Korean Missile Buildup, Yonhap News Agency, March 2, 2001, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=102&oid=001&aid=0000057623; “DPRK Deploys 100 Nodong-1 Missiles Since 1998,” Chosun Ilbo, March 2, 2001; “North Korea Delays Launch Preparations,” Hankyoreh, July 8, 1999; “North Korea Building Tunnels in Three Locations Including Yongrim,” Yonhap News, June 30, 1999, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=001&aid=0004544324; and “Where Has North Korea Hidden Its Missiles – 10 Launch Sides Including China Border Region,” Segye Ilbo, June 8, 1999, http://www.segye.com/newsView/19990708000053.

The Taepodong-1 may have simply been superseded by other systems or was a technology demonstration project and never operationally deployed. From the late 1990s through 2006 the U.S. did not view the system as being operational and in 2009, NASIC dropped it from the intermittently published Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report. National Air and Space Intelligence Center, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: National Air and Space Intelligence Center), NASIC-1031-0985-09, April 2009, p. 17; National Air and Space Intelligence Center, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: National Air and Space Intelligence Center), NASIC-1031-0985-06, March 2006, p. 10; Park Yang-su, “North Korea Deploying 2 New 4,000 km Missiles in 2 Locations,” Munhwa Ilbo, May 4, 2004, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=021&aid=0000068194; Kim Yong-suk, “The entire Northeast Asia in the range of ‘Taepodong’,” Kookmin Ilbo, February 13, 2002; Defense Intelligence Agency, A Primer on the Future Threat, The Decades Ahead: 1999-2020, (Defense Intelligence Agency: Washington, D.C.), 1999, (partially declassified), p. 79, (CREST); and Robert D. Walpole, North Korea’s Taepo Dong Launch and Some Implications on the Ballistic Missile Threat to the United States, Presentation at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 8, 1998. ↩ - Author interview data; and Kim Min-suk, ”North Korea Continues to Expand Missile Base,” Joongang Ilbo, March 6, 2001, https://news.joins.com/article/4045753; and Kim Min-seok, “North Builds Missile Power as World Debates U.S. Plan,” Korea Joongang Daily, March 12, 2001, http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=1885657. ↩

- Author interview data. ↩

- Yu Yong-won, “North Korea Continues Secret Build-up Including Construction of Three Underground Bases in Rear Area,” Chosun Ilbo, March 2, 2001, http://news.chosun.com/svc/content_view/content_view.html?contid=2001030270034; Yu Yong-won, “DPRK Deploys 100 Nodong-1 Missiles,” Chosun Ilbo, March 2, 2001, http://news.chosun.com/svc/content_view/content_view.html?contid=2001030270035; “Army Denies Report on N.K.’s Alleged Missile Deployment,” Yonhap News, March 2, 2001; Kim Kui-gun, “No Sign of North Korean Missile Buildup,” Yonhap News Agency, March 2, 2001, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=102&oid=001&aid=0000057623; and “DPRK Deploys 100 Nodong-1 Missiles Since 1998,” Chosun Ilbo, March 2, 2001. ↩

- “Pyongyang is Constructing New Sites for Ballistic Missiles,” Korea Herald, May 5, 2004; and Park Yang-su, “North Korea Deploying 2 New 4000 km Missiles in 2 Locations,” Munhwa Ilbo, May 4, 2004, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=021&aid=0000068194. ↩

- “ROK, US Said Suspecting DPRK Tested ‘New Type of IRBM’ During 4 Jul Missile Launches,” Chosun Ilbo, July 18, 2006, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2006/07/18/2006071870013.html; Yu Kang-mun, “Activity of North Korea’s Missile Launch Preparations,” Hankyoreh, September 24, 2004, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=028&aid=0000079504; Park Yang-su, “North Korea Deploying 2 New 4000 km Missiles in 2 Locations,” Munhwa Ilbo, May 4, 2004, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=021&aid=0000068194; and Yu Yong-won, “North Korea Deploys New Missile Capable of Reaching Hawaii,” Chosun Ilbo, July 7, 2004, http://news.chosun.com/svc/content_view/content_view.html?contid=2004070770392. ↩

- Author interview data; Kang Hye-ran and Lee Chul-jae, “CNN: North Korea is Constructing a New Long-range Missile Base after Summit Talks,” Joongang Ilbo, December 7, 2018, https://news.joins.com/article/23188194; Nam Min-woo, “CNN: North Korea continues to expand its unidentified long-range missile base,” Chosun Ilbo, December 6, 2018, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/12/06/2018120600526.html; Son Hyo-joo, “Government: Remained Silent so North Korea would not notice surveillance…Preparations for emergency attack completed,” Dong-a Ilbo, November, 15, 2018, http://news.donga.com/3/all/20181115/92877807/1; Jung Chung-sin, “ROK-US Joint Military Exercises, Defense Changes to Preemptive Strikes,” Munhwa Ilbo, March 7, 2016, http://www.munhwa.com/news/view.html?no=2016030701070630114001; An Du-won, Kim Min-suh, and Park Byung-jin, “North Korea, another show of missile power? … is it for talks or for use in combat,” Segye Ilbo, April 5, 2013, http://www.segye.com/newsView/20130404004770; “Press Gets 1st Look at N. Korean Mid-range Missile,” Chosun Ilbo, October 11, 2010, http://english.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2010/10/11/2010101101060.html; Kim Min-suk, “North Korea Creates a Missile Division for New Missile Capable of Reaching Guam U.S. Military Base,” Joongang Ilbo, March 10, 2010, https://news.joins.com/article/4052989; An Yong-hyun and Lee Yong-su, “Kim Jong-Un Inspects KPA Celebration with new missile reveal … Formalization of Kim Jong-un’s military acquisition,” Chosun Ilbo, October 11, 2010, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2010/10/11/2010101100037.html; Yu Yong-won, “North Korea Deploys Missile That Can Reach Guam,” Chosun Ilbo, February 24, 2009, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2009/02/24/2009022400059.html; Yun To’k-min, Assessment of North Korea’s Ballistic Missile Program, Institute of Foreign Affairs and National Security, July 18, 2006; Yi Myong-kun, “DPRK Building New Missile Bases To Target Japan, US Military in Japan,” Dong-a Ilbo, August 3, 2006, http://news.donga.com/3/all/20060803/8336357/1; “DPRK Reportedly Builds New Missile Bases Along East Coast,” Yonhap News, August 3 2006; “N.K. Building New Missile Bases,” Korea Herald, August 3, 2006; and Yang Song-uk, “North Now Building Underground Missile Bases,” Munhwa Ilbo, August 3, 2006, http://m.munhwa.com/mnews/view.html?no=20060803010302233070020; “ROK, US Said Suspecting DPRK Tested ‘New Type of IRBM’ During 4 Jul Missile Launches,” Chosun Ilbo, July 18, 2006, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2006/07/18/2006071870013.html; and “East Asian Strategic Review 2005,” National Institute for Defense Studies (Tokyo: 2005), 64-65, http://www.nids.mod.go.jp/english/publication/east-asian/pdf/2005/east-asian_e2005_03.pdf.

While occasional reports from 2004 through 2009 would mistakenly state that the missile unit housed at the Sangnam-ni base was variously equipped with the Nodong medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM), Taepodong-1 MRBM or Taepodong-2 intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), reports from that time forward have clearly stated that it is equipped with the Hwasong-10 (Musudan) IRBM. ↩ - Some ballistic missile units may train on a bi-annual rather than annual schedule. Author interview data and Yu Kang-mun, “Activity of North Korea’s Missile Launch Preparations,” Hankyoreh, September 24, 2004, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=028&aid=0000079504. ↩

- Yun To’k-min, Assessment of North Korea’s Ballistic Missile Program, Institute of Foreign Affairs and National Security, July 18, 2006; Yi Myong-kun, “DPRK Building New Missile Bases To Target Japan, US Military in Japan,” Dong-a Ilbo, August 3, 2006, http://news.donga.com/3/all/20060803/8336357/1; “DPRK Reportedly Builds New Missile Bases Along East Coast,” Yonhap, August 3 2006; “N.K. Building New Missile Bases,” Korea Herald, August 3, 2006; and Yang Song-uk, “North Now Building Underground Missile Bases,” Munhwa Ilbo, August 3, 2006, http://m.munhwa.com/mnews/view.html?no=20060803010302233070020. ↩

- The greenhouse and agricultural support activities are not unusual within the KPA as all units have a varying level of responsibility for growing their own food. ↩

- Author interview data. ↩