Nudging North Korea Towards a Test Ban

Last week, Kim Jong-un celebrated the 68th anniversary of the North Korean state with a nuclear test designed to strike fear in the hearts of North Korea’s adversaries. The largest Korean nuclear test yet—registering at a magnitude of 5.3 on the Richter scale, roughly equivalent to a 15-20 kiloton test—was supposed to demonstrate North Korea’s ability to mate a nuclear warhead to a ballistic missile. At least, this is what the official Korean Central News Agency announced shortly after the completion of the test.

Unlike other nuclear weapon states that have preferred to remain secretive about their nuclear developments, North Korea has actually touted its ability to standardize nuclear warheads (whatever that means) and use various fissile materials (a nod to its highly enriched uranium production). Earlier this year, Kim Jong-un claimed a January nuclear weapon test proved North Korea’s thermonuclear prowess, but the small yield of the test sowed significant doubt about his claim.

North Korea’s public relations intention is clear: to cast the longest shadow from its nuclear weapons tests as possible. Tests offer an opportunity to proclaim certain capabilities, whether or not the data supports it. The North’s current objective apparently is to portray its nuclear weapons program as a well-oiled machine about to produce nuclear warheads in assembly-like fashion, to be fastened atop its ever-growing and ever-capable missile arsenal. The 2016 barrage of missile tests (about half of which were successful) bolster that depiction.

The reality is likely different. North Korea is using up a portion of its plutonium with each test and while it has restarted plutonium production capabilities at Yongbyon, industrial-scale production is likely far off. The throughput of its centrifuge enrichment plant is harder to judge, at least from remote sensing. One thing is certain, however. In the last 10 years, North Korea’s nuclear program is advancing: five nuclear weapons tests (some of them successful) have clearly taught North Koreans something about warhead design, the uranium enrichment program has the potential to add further warhead options (like boosted fission warheads), and the ballistic missile program is lurching toward increased survivability. In the last six months, the military has tested, almost on a monthly basis, solid-fueled rocket motors (easier to deploy and potentially road-mobile), solid-fueled submarine-launched ballistic missiles (in April and August), and an array of short- and medium-range missiles.

Moreover, North Korea is steadily acquiring the accoutrements of a full-fledged nuclear power: it announced a nuclear doctrine and strategy (albeit crude) several years ago and apparently created its version of Los Alamos—the North Korean Nuclear Weapons Institute.

Thermonuclear weapons, intercontinental-range ballistic missiles, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles are all hallmarks of an advanced nuclear weapon capability that North Korea apparently so desperately wants to emulate. No one expects North Korea to achieve those capabilities anytime soon, but their acquisition would mark a qualitatively different threat from North Korea.

It is possible that Kim Jong-un is escalating to de-escalate: building up capabilities (whether real or trumped up) in order to strengthen his negotiating hand for a later date. It is also possible that the regime could collapse with little warning. After all, other regimes have toppled for unpredictable reasons and with unpredictable consequences. But those cases of wishful thinking distract from the urgent task at hand: to find a way forward that halts North Korean nuclear and missile development, even if only temporarily. With increased capabilities come, undoubtedly, less enthusiasm for relinquishing such capabilities.

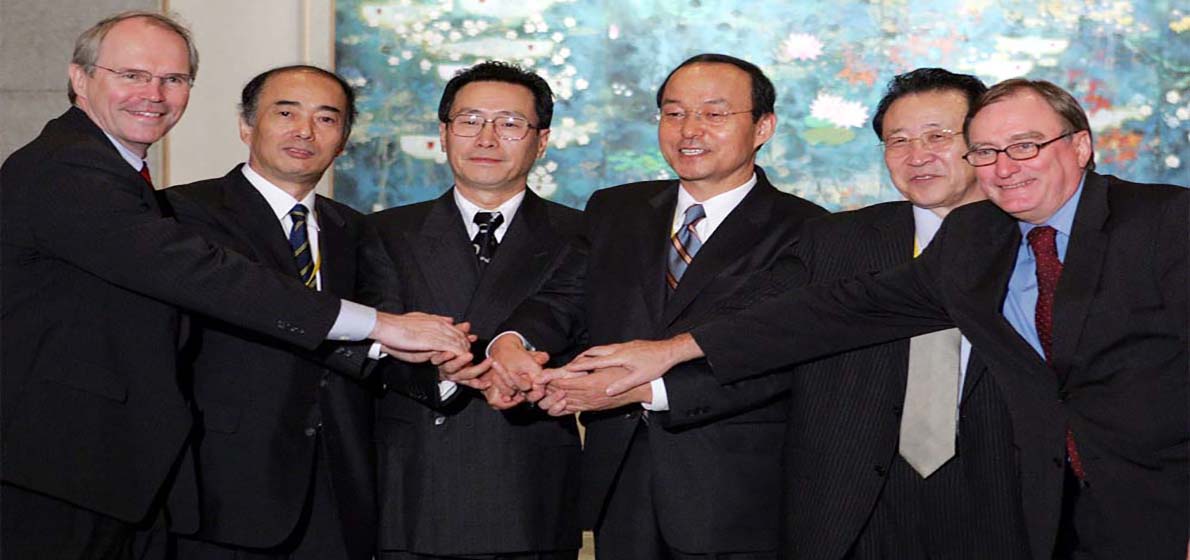

A halt in North Korean nuclear and missile tests cannot be achieved through force. Dialogue would require North Korean engagement, which has been in short supply. On the 20th anniversary of the signing of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, North Korea and the other members of the Six Party Talks (South Korea, China, Russia, Japan, and the United States) need to initiate a dialogue at least on nuclear testing with no preconditions.

One does not have to believe that dialogue alone will result in an effective agreement with North Korea to believe that without dialogue, our ability to separate fact from fiction is seriously diminished. Reducing risks from North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities may become the next U.S. administration’s “Iran,” requiring an enormous outlay of political and diplomatic capital but with similar regional and global benefits. ![]()