A Renewed Axis: Growing Military Cooperation Between North Korea and Russia

Key Findings

- The White House’s acknowledgement this week of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un’s possible trip later this month to meet Russian president Vladimir Putin is only the latest evidence of a growing military alignment between North Korea and Russia.

- Russia-North Korea cooperation may extend beyond conventional arms deals and food/energy assistance, possibly to advanced technology for satellites, nuclear-power submarines, and ballistic missiles.

- A Russia-North Korea axis complicates the security picture both in Ukraine and on the Korean peninsula.

- Even technical support by the Russian military to advance or modernize North Korea’s conventional forces could embolden Kim to adopt more coercive, even lethal use of force.

- The United States and its allies have limited policy options in addressing this new challenge.

The White House’s acknowledgement of intelligence indicating a possible meeting between North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and Russian President Vladimir Putin on the sidelines of the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok on September 10-13 to advance ongoing arms negotiations is only the latest evidence of a growing military alignment between the two countries.

Last week, the National Security Council announced that the two leaders had exchanged letters pledging to increase their bilateral cooperation and that the two countries were actively advancing negotiations to assist Russia’s war in Ukraine. U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, joined by her counterparts from Japan, South Korea and the United Kingdom, condemned such negotiations as a violation of UN Security Council resolutions on North Korea (UNSC 1874 and 2270).

In January 2023, the White House released satellite imagery of arms transfers from North Korea to the Wagner paramilitary group taking place at the Tumangang–Khasan railroad crossing on November 18 and 19 of last year. This was followed by the Treasury Department’s announcement of new sanctions in mid-August against three entities allegedly connected to arms deals between North Korea and Russia.

If Kim and Putin agree to enhance their military and strategic cooperation, including joint naval exercises with China (Russia allegedly proposed during its Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu’s visit to North Korea) and potential reactivation of the former Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance, this will add a new dimension to traditional challenges presented by both foes to U.S. security both at home and abroad.

Transactional ties

Historically, North Korea’s interest in the Soviet Union/Russia was largely derivative of its policies toward China, using cooperation with Moscow as leverage in eliciting more assistance from China, or in lieu of Beijing’s assistance during certain periods in Chinese history (e.g., Great Leap Forward, Cultural Revolution). During the Sino-Soviet split, for example, North Korea played Moscow off Beijing, as Soviet leaders sought to pull the North’s allegiance away from China. North Korea also experiences acute abandonment anxieties when Moscow draws closer to Seoul or when U.S.-Russian or U.S.-China relations are stable. Russia-South Korean normalization in 1990, for example, realized the ultimate abandonment fear for the late North Korean leader Kim Jong-il as Moscow stopped providing energy assistance at discounted prices to Pyongyang. Russian interest in North Korea is equally transactional, but at the same time relatively consistent over the centuries.

Moscow has interest in warm water ports on the Korean peninsula for its Pacific Fleet and in energy and transport infrastructure projects that connect Northeast Asia to Siberia and the Eurasian land mass through the Korean peninsula.

Arms deals to support Putin’s war in Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and the precipitous downturn in U.S.-Russian relations even before the war is the permissive condition for a tightening of relations between Putin and Kim. Russia’s arms negotiations with North Korea reflects its growing international isolation and the deplorable state of its military industrial complex that cannot meet the needs of its own armed forces. Under heavy international sanctions, North Korea also needs food and energy assistance from Russia. Each side also views opportunities in the current context that complicates the security picture for the United States and its allies. The record of quiet but substantive expanding cooperation is clear.

For example, during the emergency special session of the UN General Assembly in response to the invasion in early March 2022, North Korea expressly defended Russia’s war in Ukraine and joined Russia, Belarus, Eritrea and Syria to veto the UN resolution that condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Four months later in July, North Korea recognized the independence of the two Russian-occupied states— Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and Luhansk People’s of Republic (LPR)—in eastern Ukraine and announced its plan to send workers to Donetsk after the country reopens the border. Russia also took actions in support of DPRK leveraging its position in the Security Council to block all UN-mandated punitive action in response to DPRK ballistic missile tests in 2022 and 2023. Russia joined North Korea in condemning military exercises by the U.S., the ROK, and Japan, calling them “provocative” and attesting that “Russia stands in the same trench with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.”

Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu’s visit to North Korea in July 25-27, 2023, the first by a Russian Defense Minister since 1991, reflects a significant uptick in bilateral cooperation. Shoigu was the highest-ranking foreign official to attend North Korea’s “Victory Day” celebrations to mark the 70th anniversary of the Korean war armistice in spite of the COVID lockdown in North Korea. And North Korean leader Kim Jong-un provided unusually visible VIP treatment to Shoigu, including a one-on-one meeting and a personal tour of the military exhibition, announcing to state-run media that he would expand military cooperation with Moscow. In his letter to Kim, Putin vowed to increase political, economic, and security ties with North Korea and said that North Korea’s “firm support to the special military operation against Ukraine and its solidarity with Russia on key international issues highlight [their] common interests and determination to counter the policy of the Western group.”

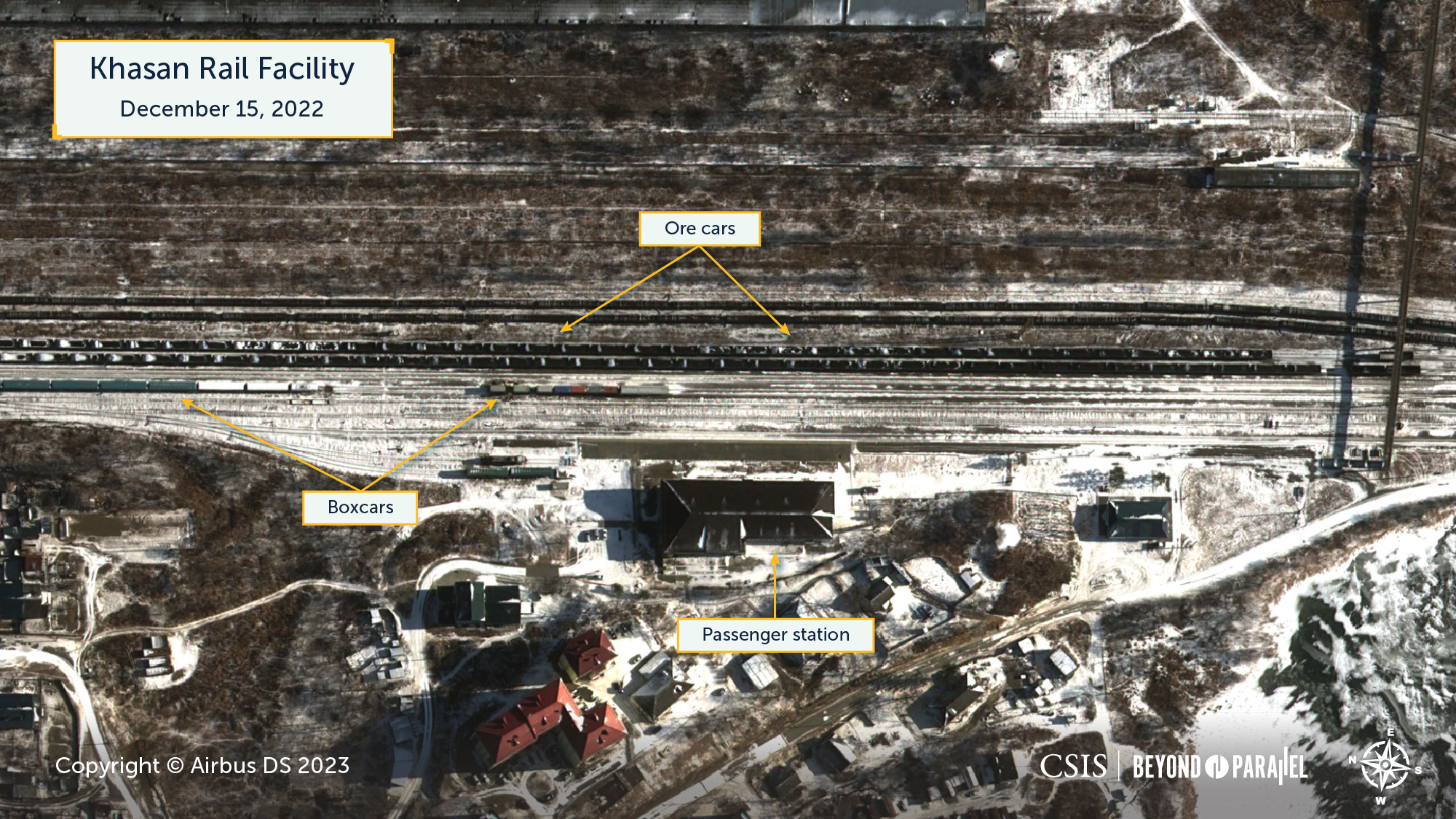

Shoigu’s visit, moreover, came on the heels of growing activities in railway traffic across the Russo-North Korean border. CSIS Beyond Parallel exclusive satellite imagery analysis observed an increase in the number of iron ore, petroleum and food railcars at the Tumangang–Khasan railroad crossing between late November and mid-December 2022 (see Graph 1) shortly after the DPRK arms transfer to the Wagner Group in mid November (see images 1 and 2 below).

Graph 1: Number of box cars observed at Khasan and Tumangang in late 2022 after Wagner arms transfer. Ore cars were observed at Khasan, and oil/petroleum tank cars were seen at Tumangang. (Source: Beyond Parallel)

Image 1: Close-up view of the Khasan rail facility, December 15, 2022. Ore cars and boxcars are seen at the station. (Copyright © Airbus DS 2023).

Image 2: Close-up view of the Tumangang rail facility, December 15, 2022. Oil/petroleum tank cars seen at the station. (Copyright © Airbus DS 2023).

Possible missile cooperation

The extent of this growing alignment likely extends beyond one-off arms-for-food and energy deals to more robust missile cooperation that may help to explain the latest developments in DPRK ICBM capabilities. There are a number of reasons to suspect, using only open-source materials, that claims of such cooperation are more than speculative.

First, there is a long history of bilateral missile cooperation dating back to as early as the 1960s when the Soviet Union provided the V-75 Dvina (SA-2a Guideline) surface-to-air missile to North Korea, which eventually became the latter’s first missile system. The Soviet also transferred other types of missiles, such as S-2 Sopka (SSC-2b SAMLET) coastal-defense cruise missile and P-20 (SS-N-2 STYX) anti-ship missile and also gave technical training to North Korea on assembly and maintenance.

Second, North Korea’s ballistic missile and submarine launched ballistic missile programs have benefited significantly from Soviet technology. After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, North Korea recruited many Russian scientists and engineers who helped advance the program. Some experts contend that development of missile systems like the Hwasong-12 IRBM and Hwasong-14 ICBM is based on a modified North Korean version of the Soviet RD-250 engine.

Third, it is challenging in the least to explain recent significant improvements in DPRK ICBM technology based solely on the North’s capabilities. Some experts contend that the successful launches of the Hwasong-18 ICBM on April 13 and July 12, 2023 show a striking resemblance to the Russian Topol-M, providing DPRK with solid propellant ICBMs with countermeasure deployment canisters. Although there has been debate over this assessment, these are capabilities that are hard to fathom the North Koreans’ demonstrating or deploying, certainly over such a short period of time, without outside help.

Finally, it is not by coincidence that a week after Shoigu’s visit to DPRK, Kim Jong-un visited major munitions factories, where he expressed satisfaction with the country’s capacity for the serial production of large-caliber artillery rockets and announced a drive to mass produce other capabilities such as engines for strategic cruise missiles and armed unmanned aerial vehicles.

The implications of the growing military alignment between North Korea and Russia for the U.S. are clear. The tactical advantage that each foe gains in expanding cooperation complicates U.S. efforts in the war in Ukraine. It is noteworthy in this regard that U.S. officials in condemning DPRK munitions transfers to Russia no longer downplay the supplies as trivial. It also complicates U.S. efforts at shoring up extended deterrence on the Korean peninsula with its South Korean ally as North Korea demonstrates increasingly more capable and potentially survivable ICBMs. In this regard, Putin may be trying to demonstrate that actions taken in Europe by the U.S. will have consequences not just in that theater but also in the Indo-Pacific detrimental to U.S. interests.

All in all, Russia may be the biggest enabler of North Korea today, even more so than China. The latter has not been supportive of the denuclearization agenda and has not helped to bring Pyongyang back to the negotiating table, given the state of U.S.-China relations. But Beijing reportedly has been opposed to North Korea conducting a seventh nuclear test. This stands in contrast to potential arms and missile deals with DPRK being negotiated by Moscow, which could transfer sensitive military technology that could accelerate North Korea’s military satellite, nuclear submarine, and ICBM programs. Any Russian technical support that could help advance or modernize the Korean People’s Army’s conventional forces are also an area of concern. According to the recent National Intelligence Estimate declassified by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Kim Jong-un could fully leverage his growing WMD capabilities to employ nuclear coercion strategies using conventional capabilities, even potentially the lethal use of force.

Limited Options

There are limits to what the U.S. can do in response to the new Russia-DPRK axis. But there are some policy options that Washington could consider. First, the United States can push the envelope in terms of the deliverables from the Camp David trilateral summit in August such as multi-domain trilateral exercises and enhanced information sharing. The United States can also expand missile warning sharing data arrangements with the ROK and Japan. Second, to counter and deter further ICBM launches by North Korea, Washington could declare that the US and its allies will not rule out neutralizing missiles in flight (particularly if they are not on a lofted trajectory) or on the launchpad. Third, Washington should list Russian entities and individual involved in any DPRK arms deals and seek similar sanctions from like-minded parties. Fourth, it should warn Beijing about neither participating nor condoning the Russia-DPRK axis. Fifth, it should continue to draw attention to Russia-DPRK cooperation at upcoming forums like UN General Assembly, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations this fall by downgrading intelligence for public consumption as part of the DNI transparency program.