Making Solid Tracks: North and South Korean Railway Cooperation

A CSIS Study of Railway Cooperation and Connections on the Korean Peninsula1

Key Points

• This report is the first in a series of CSIS original reports on the inter-Korean and Korea-Eurasian railway connections including analysis, satellite imagery, and an overview of technical specifications.

• With the November 30, 2018 commencement of the third inter-Korean railway survey, North and South Korea are moving forward with inter-Korean railway cooperation as a key engine for advancing inter-Korean reconciliation and building the infrastructure for eventual unification. A possible inter-Korean groundbreaking ceremony for railways in the near future would mark a significant diplomatic and geopolitical accomplishment.

• The poor maintenance and outdated technology of existing North Korean railways, as well as differences in the physical infrastructure including stations, rail weights, and gauges, presents challenges for commercially viable cooperation. The resulting necessary harmonization and modernization railway projects will be costly and time intensive.

• However, South Korea’s membership in the Organization for Cooperation between Railways (OSJD) – an inter-governmental organization managing international rail transport in Europe and Asia – adds greater potential for the commercial success of current railway cooperation efforts than those undertaken earlier in the 2000-2008 “Sunshine Policy” era.

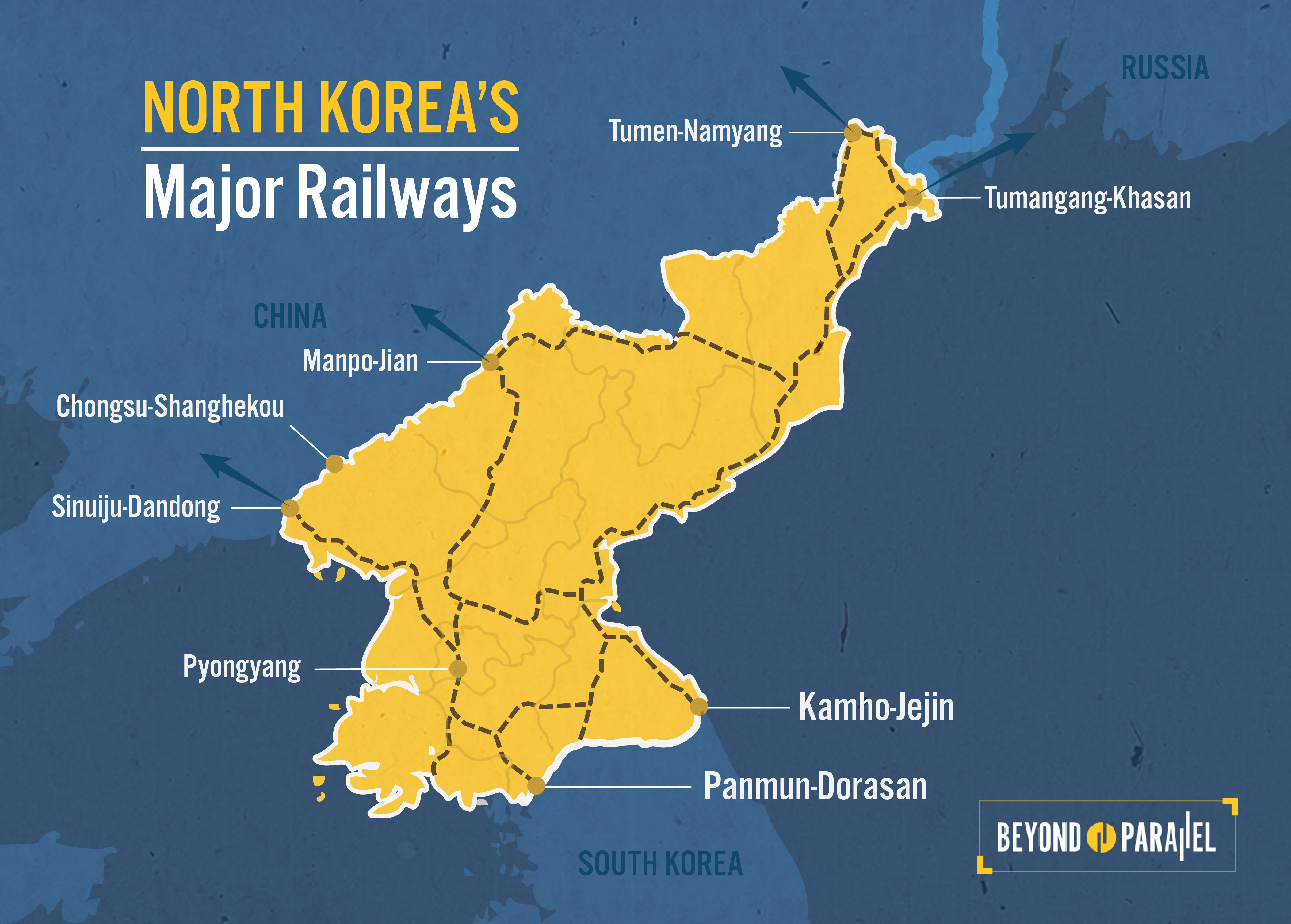

• There are currently two North Korea-South Korea, four North Korea-China, and one North Korea-Russia rail connections. These connections and facilities vary considerably in size, capabilities, and operational status. Upgrades to and maintenance of these facilities will also require considerable investments of time and funds. (See the Beyond Parallel report on North Korea-China and North Korea-Russia rail connections.)

North and South Korea are moving forward with inter-Korean railway cooperation as a key engine for advancing inter-Korean relations. Inter-Korean railway cooperation in 2018 was initiated by the April 27 Panmunjom Declaration.2 Signed on April 27, 2018 by South Korean president Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un after the first 2018 inter-Korean summit, the Panmunjom Declaration includes an agreement to implement various infrastructure projects outlined by the 2007 October 4 inter-Korean agreement. Inter-Korean exchanges throughout the summer and fall continued to re-affirm joint commitment to railway cooperation. After a pause of several months, the third 2018 joint railway survey began on November 30. This third survey is expected to run for 18 days, cover two rail lines, and include a six-car train crossing the DMZ from South Korea into North Korea. A sanctions exemption granted by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on November 24 paved the way for this next step in the inter-Korean railway cooperation. An inter-Korean groundbreaking ceremony for railways on the eastern and western coasts is expected by year’s end. However, given delays in undertaking the third joint survey the ceremony’s timeline may now be subject to change.

Should inter-Korean cooperation lead to re-connection of North and South Korea’s railways, the Korean peninsula would then be integrated into a rail network spanning the Eurasian continent through China and Russia. This would mark a significant diplomatic and geopolitical accomplishment for the Korean peninsula. Once connected, however, a significant modernization and harmonization process will need to take place to fully integrate the systems in a commercially viable way. Physical track infrastructure varies greatly, signal systems differ, and clearances for stations are not compatible. For example, while all of South Korea and a majority of North Korea uses 1,435 mm gauge track, the North Korean system actually use a range of gauge widths. Furthermore, supporting infrastructure such as communication, energy grids, and even emergency response systems also need to be modernized and harmonized. These projects will all be costly and time intensive.

One important development that sets railway cooperation efforts in 2018 apart from earlier inter-Korean railway engagement is South Korea’s membership in the Organization for Cooperation between Railways (OSJD). South Korea became an official member of the OSJD by unanimous vote on June 7, 2018. Membership in the OSJD, the organization which manages international rail transport in Europe and Asia, now allows South Korea to participate in the Trans-China Railway and the Trans-Siberian Railway. While South Korea has actively sought membership in the OSJD since 2015, these efforts were previously unsuccessful given a lack of support from North Korea—an already registered member of the organization.

Considerations and Challenges for Connections: Track, Weights, and Gauges

The state of the existing railways’ physical infrastructure presents challenges for commercially viable railway connections. First, train speeds are slower in North Korea than in South Korea due to irregular maintenance and old technology.3 However, the actual design speeds also differ between the two systems. South Korean tracks range from 70 to 350 kilometer per hour while North Korean tracks have design speeds that range from 40 to 100 kilometer per hour. 4 Rail weights also differ. Those in South Korea range from 50 to 60 kilograms per meter while those in North Korea range from 37 to 50 kilograms per meter.

South Korea, China, and Western Europe use standard-gauge railway with a track gauge of 1,435 mm. However, Russia, Mongolia, and other Central Asian countries use a gauge of 1,520 mm. 5 North Korea uses the standard 1,435 mm track gauge for 87 percent of its railway. 6

One or more columns doesn't have a header. Please enter headers for all columns in order to proceed.

Table Note: The track grade for South Korea is classified according to the respective design speed of the railway. However, tracks are classified in North Korea according to their economic and political significance. North Korean track grades, therefore, range from 1 to 4 and are then further classified into five sub-categories according to technical specifications from A to E. Table adapted from Sang-Gyun Kim (김상균), “Comparative Analysis on the Railway Construction Criteria with Regard to the Trans-Korea Railway Project and the Railway Modernization of DPRK (남북철도 현대화를 위한 남북한 철도건설기준 비교 분석),” Journal of the Korea Railroad Association (한국철도학회논문집) 12, no. 6 (2009): 1014.

Moreover, differences in stations also need to be addressed. South Korean railway tracks have platforms that are 500 mm in height and high-level platforms that are 1135 mm in height. North Korean railway tracks have platforms that are 300 mm in height and high-level platforms that are 1200 mm in height. The clearance of railway stations in South Korea is 6,450 mm. The clearance of railway stations in North Korea is 6,000 mm. In order to accommodate South Korean rail cars, North Korea’s railways and stations need to extend their clearance by 450 mm. The current Annex to the Basic Agreement addresses the management of issues related to train length (Chapter 2, Article 9) and station clearance (Chapter 4, Article 26). However, it does not include much reference to other architectural and engineering differences between the tracks and gauges of North and South Korean railways.

Railway Connections Beyond the Peninsula

Should inter-Korean cooperation result in the re-connection of the railways in North and South Korea, the rail networks of the Korean peninsula can then be joined with those across the Eurasian continent through China and Russia. There are currently seven rail connections between North Korea and China, Russia, and South Korea. These connections and facilities vary considerably in size, capabilities, and status. As with the considerations and complications facing inter-Korean connections, many of the same issues will need to be addressed as networks are integrated further. A forthcoming Beyond Parallel report will survey these seven connection points in December 2018.

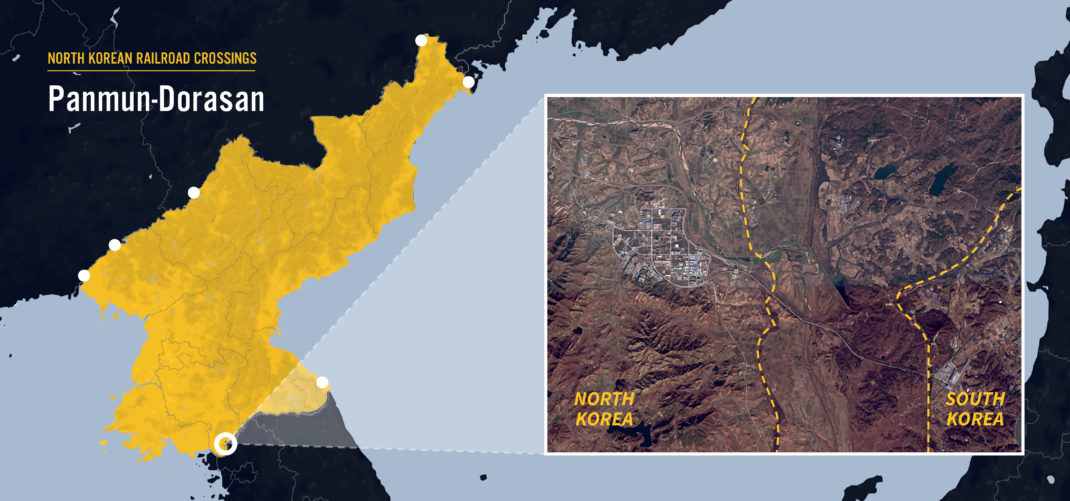

There are two rail crossings between North and South Korea:

• the Panmun -Dorasan railroad crossing connecting North Korea’s Panmun (Kaesong) rail facility with South Korea’s Dorasan rail station and

• the Kamho-Jejin railroad crossing from North Korea’s Kamho (Nungho) rail facility to the Jejin rail station in South Korea.

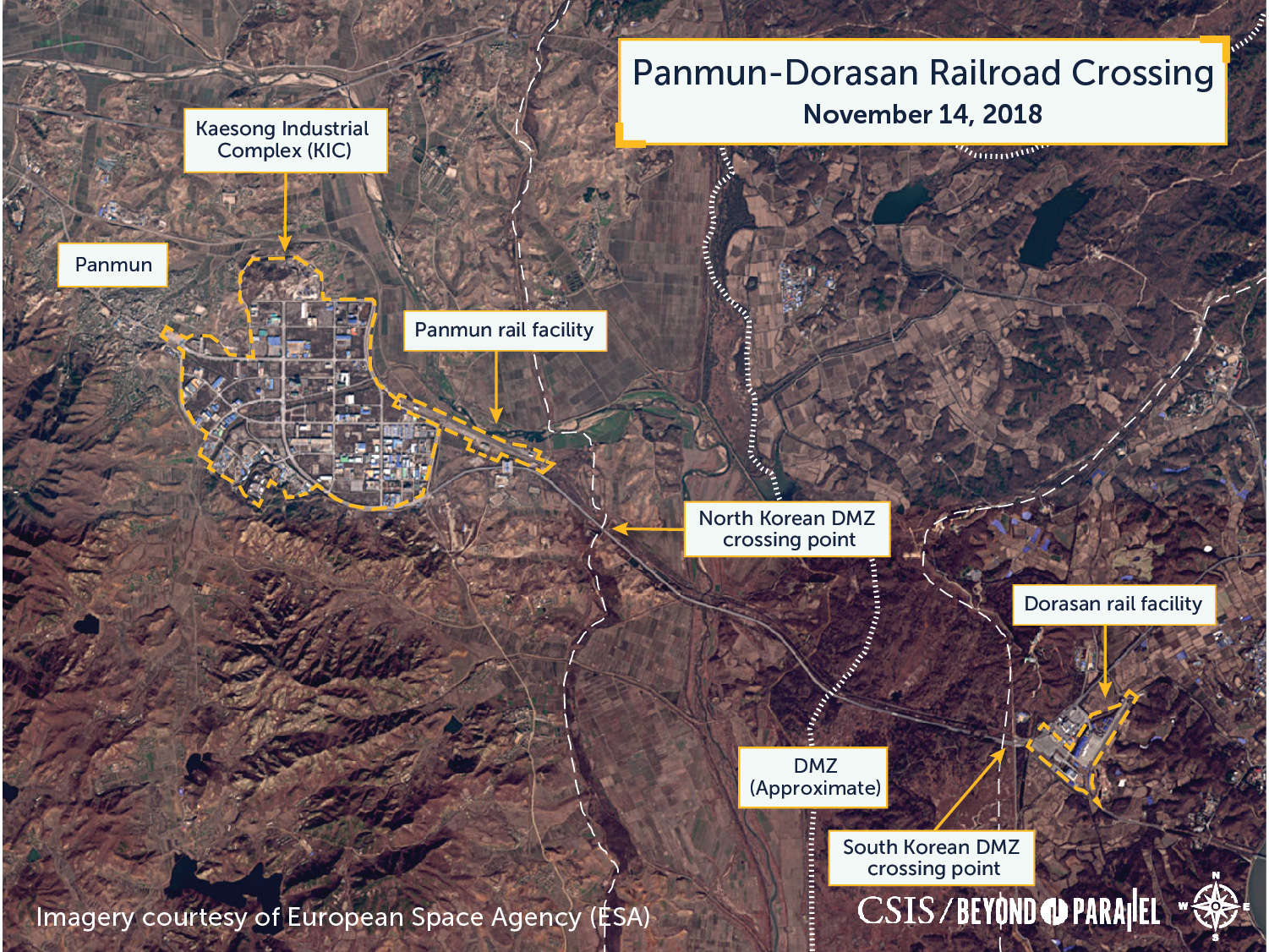

The North Korea-South Korea Railroad Crossing at Panmun-Dorasan

Crossing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea, approximately 45 kilometers northwest of Seoul, is the Panmun-Dorasan railroad crossing in North Hwanghae/Gyeonggi provinces. This crossing consists of the Panmun (Kaesong) rail facility, North Korean DMZ crossing point (37.909791° 126.679136°), South Korean DMZ crossing point (37.901744° 126.703592°), and the Dorasan rail station. This is the sole operational rail crossing between the two Koreas.

On the north side of the DMZ, the Panmun rail facility (37.928739° 126.643572°) is located 3.5 kilometers east southeast of the city of Panmun, on the east side of the Kaesong Industrial Complex and 3.8 kilometers northwest of the North Korean DMZ crossing point. The facility encompasses approximately 0.16 square kilometers and consists of:

• freight classification yard with approximately eight tracks;

• small station; and

• two locomotive servicing sheds and several small support buildings.

A review of satellite imagery shows that there has been essentially no rail activity here since the closure of the Kaesong Industrial Complex in 2016.

Located on the south side of the DMZ, at the South Korean DMZ crossing point, is the Dorasan rail station (37.898521° 126.709734°). The station encompasses approximately 0.33 square kilometers and consists of:

• modern passenger station with approximately nine tracks;

• freight yard with four tracks;

• intermodal yard; and

• warehouses and open storage yard.

A review of satellite imagery shows that although there has been only occasional traffic at the rail station since the 2016 closure of the Kaesong Industrial Complex, the freight yard has been intermittently active in 2017 and 2018.

The Panmun-Dorasan railroad crossing and associated facilities were designed to not only service the Kaesong Industrial Complex but to also serve as the crossing point for freight and passengers on the Dandong-Sinuiju-Pyongyang-Seoul-Busan route. Although this vision has yet to be realized, if the political situation improves and economic cooperation between North and South Korea increase, this will be the primary rail connection between the two nations.

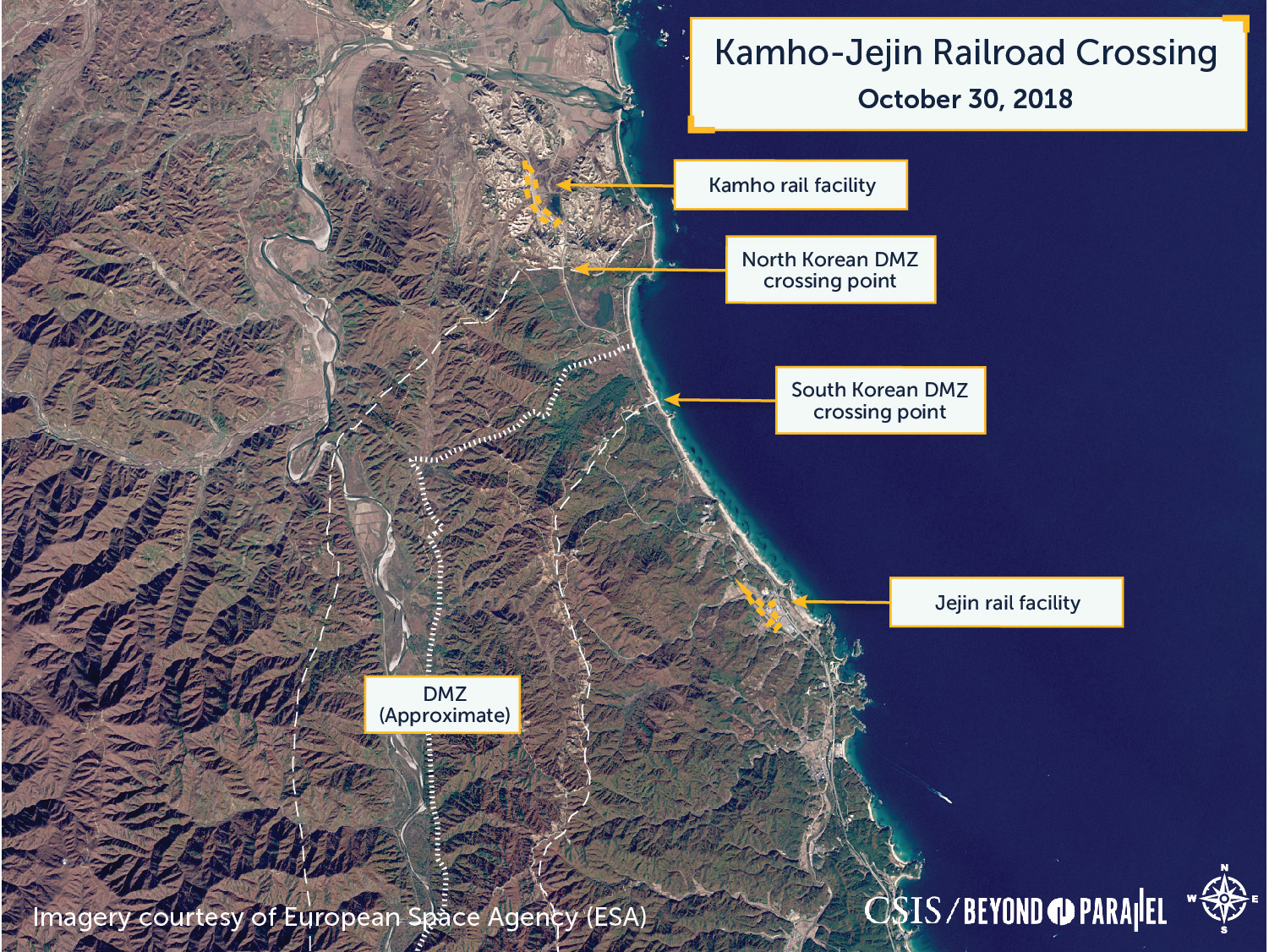

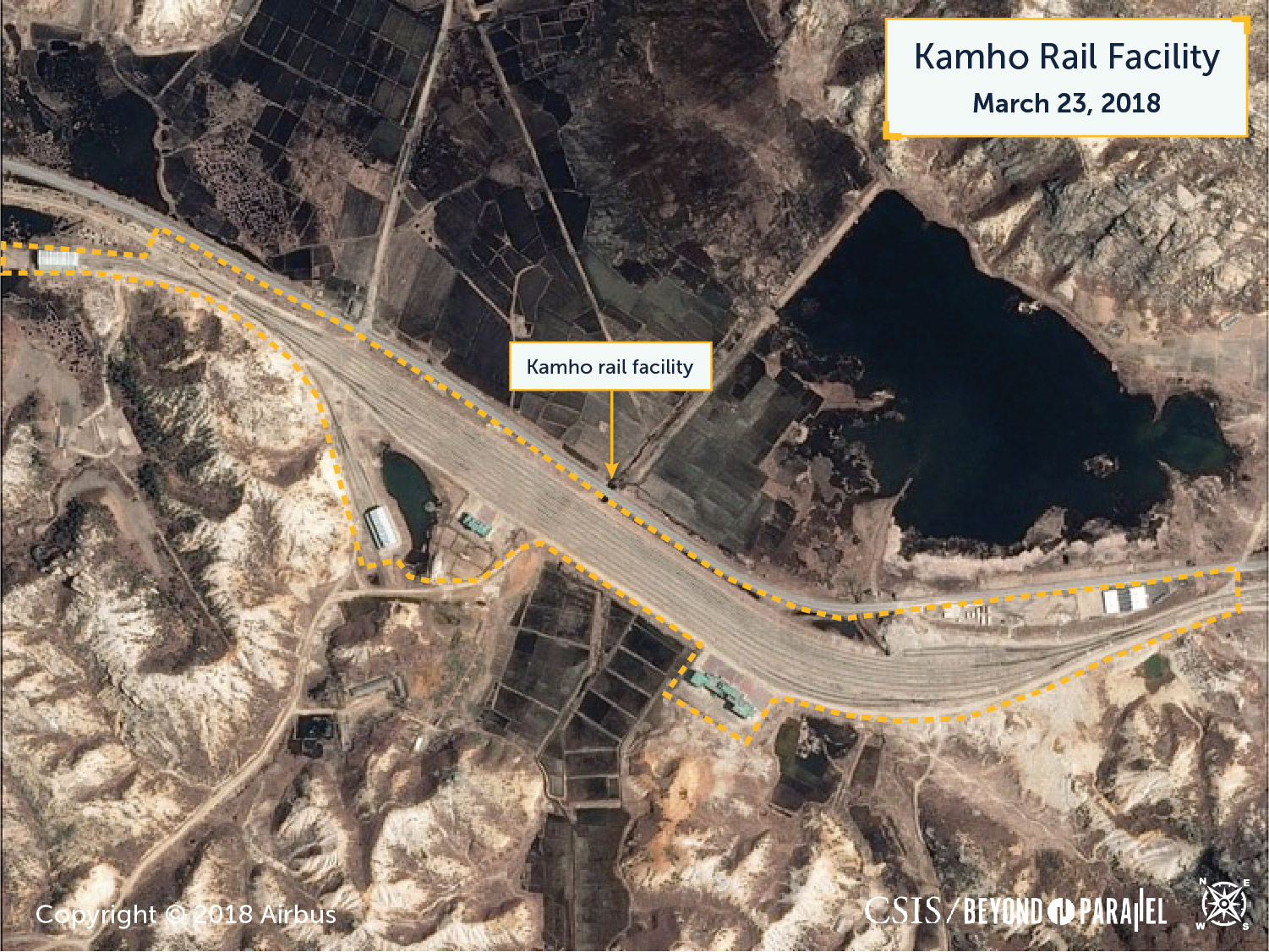

The North Korea-South Korea Railroad Crossing at Kamho-Jejin

Crossing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea, approximately 52 kilometers north northwest of the South Korean city of Sokcho, is the Kamho-Jejin railroad crossing in Kangwon/Gangwon provinces. This crossing consists of the Kamho (Nungho) rail facility, North Korean DMZ crossing point near Kusan-bong (8.629070° 128.342263°), South Korean DMZ crossing point near Anho (38.604910° 128.361044°), and the Jejin rail station. This is the second rail crossing between the two Koreas although it is not operational.

On the north side of the DMZ, the Kamho rail facility (38.643086° 128.335609°) is located 1.6 kilometers north of the North Korean DMZ crossing point and encompasses approximately 0.17 square kilometers. The facility consists of:

• freight classification yard with approximately nine tracks;

• a small station that appears incomplete; and

• two locomotive servicing sheds and several small support buildings.

A review of satellite imagery shows that while the track at the Kamho rail facility appears complete the remaining support infrastructure is incomplete. Since its construction in 2004-2006 and test railway runs in 2007-2008 no rail activity has been observed at this facility in satellite imagery. Both these conditions are undoubtedly due to the fact that while rail line extends south across the DMZ to the Jejin rail station it ends there and is not connected to the South Korean rail system.

Located on the south side of the DMZ, 4.8 kilometers south of the South Korean DMZ crossing point, is the Jejin rail station (38.567815° 128.388985°). The station encompasses approximately 0.11 square kilometers and consists of:

• a passenger station and small freight yard with approximately five tracks; and

• an unloading dock, warehouse and several other buildings.

A review of satellite imagery shows that while the track and Jejin rail station are essentially complete, the track from the north terminates here and is not connected to the South Korean rail system. Since its construction in 2004-2006 and test railway runs in 2007-2008 no rail activity has been observed at this facility in satellite imagery.

Should economic cooperation between North and South Korea increase it is logical that the Kamho-Jejin railroad crossing would be connected to the South Korean national rail system. Given sufficient political interest and financial investment for rail line development this crossing could serve as critical point for a major rail route along the east coast of the Korean peninsula connecting China and Russia to the ice-free ports of Pohang and Busan.

Inter-Korean Rail Cooperation: Historical Context

2018 railway cooperation between the two Koreas builds on efforts from July 2000 through November 2008. Until earlier this year, these cooperative efforts had been suspended for nearly a decade. North and South Korea conducted ground breaking ceremonies, numerous inter-Korean railway cooperation committee meetings, high-level exchanges, joint surveys, and test runs from 2000 and 2007. The culmination of those efforts resulted in a total of 444 freight exercises involving 310.9 tons of freight crossing the DMZ on the Gyeongui line from December 2007 until being suspended in November 2008.

Inter-Korean Railway Project: July 31, 2000 – December 2008

Table Note: Table adapted from Korea Rail Network Authority (한국철도시설공단), 2010, 70-71; Ministry of Unification (South Korea), “5th Working-level Contact for Connection of Inter-Korean Rails, Roads,” Press Release, July 4, 2003.; and Ministry of Unification (South Korea), “Agreement from 5th Working-level Consultative Meeting on Inter-Korean Road and Railway Reconnection (July 30, 2005),” August 5, 2005.

The only formally written agreement dedicated solely to the inter-Korean railway project is the April 2004 “Basic Agreement on Rail Services between the Two Koreas” in the Kaesong Industrial Complex (KIC) Statutes. The Basic Agreement is composed of 16 articles and introduces the general principles related to joint railway operation. The agreement places the Inter-Korean Joint Railway Operation Committee in charge of deliberations on accidents, transportation planning, and security clearances. In November 2007, the two Koreas added an annex to the Basic Agreement which outlines more detailed procedures for the railways between North and South Korea. The Annex to the Basic Agreement provides additional guidelines for rail car operations (Chapter 2, Articles 4-10), freight exchanges (Chapter 3, Articles 11-25), track maintenance (Chapter 4, Article 26), rail car maintenance (Chapter 5, Articles 31-34), and accident management (Chapter 6, Articles 35-49). The Annex also provides a general protocol for the Inter-Korean Joint Railway Operation Committee in planning their meetings. It states that further measures not outlined in the existing agreement will be conducted as jointly agreed upon by the committee (Chapter 1, Article 2).

References

- The authors wish to thank Sea Young (Sarah) Kim of the Georgetown University MA in Asian Studies program and the CSIS Korea Chair for her invaluable research in support of this project. ↩

- Specifically, the Panmunjom Declaration states, “the two Koreas will adopt practical steps towards the connection and modernization of the railways and roads on the eastern transportation corridor as well as between Seoul and Sinuiju for their utilization.” This commitment to the inter-Korean railway project was reaffirmed by the Pyongyang Joint Declaration, signed after the third inter-Korean summit in 2018 on September 18-20. In this declaration the two Koreas further “agreed to hold a ground-breaking ceremony within the year for the connection of railways and roads along the east and west coasts.” ↩

- According to the Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS), North Korea’s railway track was estimated to be 5,302 km as of 2014, which is around 1.5 times more than the 3,590 km track of South Korea. Around 80 percent of North Korean tracks are underground while around 68 percent of South Korean tracks are underground. If accounting for the double-tracks of South Korean railways, however, South Korea has more railway tracks (8,465 km) since the majority of North Korean railways are single-tracks. Many of the existing North Korean railway tracks were also inherited from the Japanese colonial era, and railway technology has largely remained stagnant for over two decades. “North Korea’s Railway (북한 철도 교통),” Korean Statistical Information Service (국가통계포털), Data retrieved on August 10, 2016. ↩

- Sang-Gyun Kim (김상균), “Comparative Analysis on the Railway Construction Criteria with Regard to the Trans-Korea Railway Project and the Railway Modernization of DPRK (남북철도 현대화를 위한 남북한 철도건설기준 비교 분석),” Journal of the Korea Railroad Association (한국철도학회논문집) 12, no. 6 (2009): 1014. ↩

- Suk Hi Kim, “The Strategic Role of North Korea in Northeast Asia,” in Suk Hi Kim, Terence Roehrig and Bernhard Seliger (eds.), The Survival of North Korea: Essays on Strategy, Economics and International Relations (Jefferson, NC: 2011), 72. ↩

- Korea Rail Network Authority (한국철도시설공단), Research on Integrated Rail Network Project: Final Report (통합철도망 구상 연구용역: 최종보고서) (Daejeon: 2010), 57. ↩