Mining North Korea: Magnesite Production at Ryongyang Mine

“We must improve the sectoral structure of the people’s economy, develop all sectors harmoniously, and secure world-class competitiveness in the magnesia industry and the graphite industry.”—Kim Jong-un, Speech at Supreme People’s Assembly, 2019

Key Points

- Ryongyang Mine is the largest magnesite mine in North Korea and one of the largest in the world. However, satellite and ground imagery show the infrastructure and technology in use at the mines is dated and obsolete when compared to world standards.

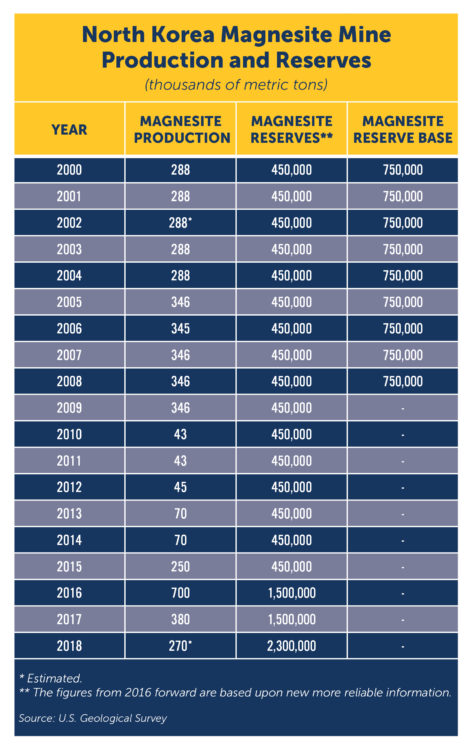

- North Korea has immense non-ferrous and rare-earth mineral reserves, including an estimated 2.3 billion metric tons of magnesite. While mine production of magnesite dropped in 2018 due to international sanctions imposed the previous year, magnesite remains an important commodity for North Korea.

- Should rapprochement happen between North and South Korea, South Korea would be interested in North Korean exports of magnesia, however tremendous investment would be needed to make magnesite mining at Ryongyang mine efficient and commercially profitable.

- Even if international sanctions are lifted allowing North Korean magnesia exports to increase, significant investment would be needed for North Korea’s magnesite mining industry to operate at modern global standards.

- Since 2008-2009, China has established long-term extractive industry contracts of North Korea’s rare-earth and non-ferrous minerals, including magnesite, to benefit the economies of inland provinces Lioaning and Jilin. A component of this strategy could be to lock out competitors and influence world market pricing.

North Korea is a nation with immense non-ferrous and rare-earth mineral reserves. Among these is magnesite, which has been mined in commercially viable quantities since the Japanese colonial period. The United States Geological Survey estimates North Korea has 2.3 billion metric tons of magnesite reserves and that its total 2018 mine production of magnesite was 270,000 metric tons. While this is a decline from 380,000 metric tons during 2017 due to international sanctions imposed during 2017, magnesite remains both an important export and domestic commodity for North Korea. Since 2010, North Korea has exported magnesia to a number of countries including, but not limited to China, the Netherlands, and Germany. Of these, China is, by a large margin, North Korea’s largest customer for magnesite. The Korean International Trade Association estimates North Korea exports 130-180 thousand tons of magnesite to China each year. Foreign analysts, especially in South Korea, believe China’s large long-term purchases of North Korean rare-earth and non-ferrous minerals, including magnesite, are a component of a strategy to lock out competitors and influence world market pricing.1

The mining and export of magnesite, and the domestic production of products from it, are important to the North Korean government and economy as indicated by the praise the Ryongyang Mine and other magnesite mines and production facilities have routinely received from Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il, and Kim Jong-un. For example, in remarks at an October 2011 field guidance, Kim Jong-il reiterated great satisfaction over the laudable feats performed by the workers of the above-said industrial establishments and the Taehung and Ryongyang mines in their endeavors to make a breakthrough toward the fulfillment of their national economic plans.

Magnesite Reserves, Production, and Exports

Estimates of North Korea’s magnesite reserves and production output have fluctuated considerably over the last 20 years.2 The wide range of estimates is due to a combination of the limitations of available reliable data, methodology used in calculations, and the political agendas of the reporting sources.3 Two of the more readily accessible and reliable sources concerning North Korea’s magnesite reserves and production output are the U.S. Geological Surveys (USGS) annual Mineral Commodity Summaries and Minerals Yearbook.4 The Magnesium Compounds entry in the Mineral Commodity Summaries 2019 reports North Korea has 2.3 billion metric tons of magnesite reserves, tying it with Russia for the world’s largest magnesite reserves. The Mineral Commodity Summaries 2019 also reports North Korea’s 2018 mine production of magnesite was 270,000 metric tons, placing it tenth in the world. This figure was down from 380,000 metric tons during 2017. The year-on-year decline in magnesite production from 2017 to 2018 can largely be attributed to a decrease in magnesia exports from North Korea to China and other countries driven by restrictions from international sanctions in 2017. While exports to China resumed in 2018, North Korea’s exports to other countries did not.4

North Korea’s magnesite reserves are primarily distributed in Hambuk and Hamnam provinces in the northeastern part of the country. With 90 percent located in the Tanchon area of Hamnam province. The remaining 10 percent are located in the Paegam-gun area of Ryanggang province and scattered around the nation.5 Among the magnesia related facilities within these two provinces are the Namgye Mine, Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory, Ryongyang Mine, Saengjang Mine, Songjin Refractory Factory, Ssangyong Mine, Taehng Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory, Taehng Mine, and Tanchon Magnesia Clinker Factory.6

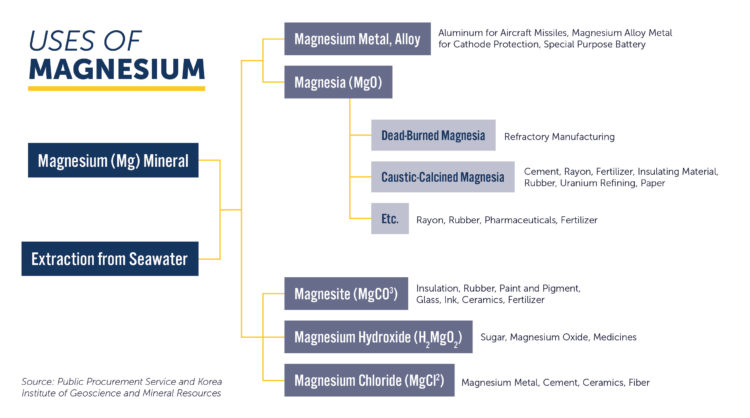

Magnesite in its various forms is used in a wide range of industrial, civilian and military applications. For example, “…light magnesia is used as raw materials for livestock feed, fertilizer, wastewater treatment, exhaust gas adsorbent, building materials, glass fiber, special glass, glassware coating agent, absorbent and catalyst for uranium oxide recovery and antacid. Small magnesia is used as refractory brick to block heat transfer since it is the most heat resistant ceramic oxide. Refractories inside the blast furnace are also made of small magnesia. Molten magnesia is used for special refractory bricks and electric insulators of heating devices. 99% or more high-purity magnesia is used in optical equipment, nuclear reactors, [and] rocket nozzles.”7

Ryongyang Mine

Ryongyang Mine (40.901815 128.804703), also known as Yongyang Mine, is located in Tanchon-gun (Tanchon County), Hamnam (South Hamgyong province) approximately 330 kilometers north-northeast of Pyongyang.8 Located on the slopes of Paekkumsan, the mine is the largest magnesite mine in North Korea and one of the largest in the world.9

Surface mining of magnesite in the Ryongyang area began during 1942 and following World War II these activities were taken over in 1948 by the government of the newly established Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). In 1954, the magnesite mines and processing facilities in Tanchon-gun were reportedly organized under the Korea Magnesia Clinker Industry Group based in Pyongyang.10 Kim Il-sung visited the Ryongyang Mine in April 1961 and named the mountain on whose magnesite-rich slopes it was built, Paekkumsan (i.e., magnesite mountain). Kim and others would subsequently refer to the mountain as “gold mountain” indicating the value of the mountain to the regime.

Today the Ryongyang Mine is a component of the considerably larger General Bureau of the Tanchon Area Mining Industry (sometimes referred to as the Tanchon Area General Mining Bureau) that oversees mining in Tanchon-gun. This bureau is subordinate to the Ministry of Mining Industry. Magnesite mining operations under the bureau extend north from the port city of Tanchon distributed along the valleys of the Namdae-chon (i.e., Namdae stream) and Puktae-chon (i.e., Puktae stream).

Ryongyang Mine, rather than being a single mine, is more accurately a mining complex consisting of numerous mining, processing, support and housing activities that extend approximately 15 kilometers along the Puktae-chon valley and its branches. The Puktae-chon valley is served by the Kumgol rail line that passes through 24 railroad tunnels before reaching the Kumgol rail station and classification yard.

Ryongyang Mine is mentioned numerous times in both North Korean and South Korean reports and described as consisting of collection of large-scale open-pit excavation, underground mines, Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory and a number of industrial support facilities (e.g., railroad stations, electrical substation, etc.).11 Additionally, there are housing, agricultural, social and other facilities (e.g., hospital, Ministry of People’s Security, etc.) that support the workers from the mine and political and social entities. Although the precise details concerning the mines organization and the specific locations of its various activities and facilities are lacking, the following are among the most often reported:12

- April 5th shaft

- Chongnyong pit

- Crushing, selecting, dressing and treating processes

- Engineering section

- General control room (reportedly at the Kumsan Pit)

- July 1st shaft

- June 5th pit

- Kumsan pit

- Kumsan pit number 2 (honored with the title of Twice Three Revolution Red Flag)

- Long-distance conveyor belt system

- Nomber 4 pit, Tonsan Branch

- Power substation

- Railroad stations and terminals, including ore loading facilities

- Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory (produces light burned magnesia)

- Ryongyang Industrial Engineering University (presumably a mining school)13

- Tonsan shaft

Additionally, what has been identified as the Komdok (Kumgol) No. 3 Mine is located southeast of Kumgol-tong 2 (more commonly known as Kumgol or Komdok). It is unknown whether this mine is considered to be a component of the larger Ryongyang Mine complex.14

With the combination of both satellite imagery and open source reporting (including North Korean provided ground imagery), some of these activities can be located with relatively good accuracy. Many, however, simply cannot be located with accuracy at the present time due the lack of reliable information and challenges in disambiguating the information that is available.

Both the surface and underground mining of magnesite at the Ryongyang Mine complex is centered around the original Ryongyang Mine and the town of Kumgol.

Scarring from past large-scale surface mining activities is clearly evident around the main Ryongyang Mine in satellite imagery. This scarring stretches north of the village of Yongyang-ni, and west of the Puktae-chon, for approximately 2.5 kilometers. All of these surface mining areas appear to have been abandoned or are largely inactive since the flooding in 2012. A long-distant conveyor belt system, leading to a mine shaft northeast of the main mines processing facility, was razed sometime during 2011-2012. Immediately west of the processing facilities are two portals leading to an underground mine. Despite numerous North Korean propaganda photographs showing extensive surface mining operations with large numbers of shovels and large mine dump trucks hauling ore, satellite imagery from the past five years provides no evidence to support this. Combined with the general lack of activity at the portals and processing facilities, and the minimal rail movements observed along the rail spur line feeding the mine, it is likely that this facility is operating a low level or intermittently.

Approximately 1.5 kilometers north of the main Ryongyang Mine, and on the east side of the Puktae-chon, is a large electrical substation. Given its size and location it likely supports the mining activities at the main Ryongyang Mine, Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory and various facilities around Kumgol-tong 1 and Kumgol.

Two kilometers north of the main Ryongyang Mine, a small branch valley extends to the west of the Puktae-chon towards the town of Kumgol-tong 1. Along with a number of small mining activities up this valley there is a mining support base at its lower end. This support base is also feed by a rail spur line and consists of several open storage areas, a coal storage yard and various small support facilities (e.g., workshops, garages, etc.).

Immediately east of this valley, but still on the west bank of the Puktae-chon, is an underground mine. This mine is likely substantial as it has two portals and is served by its own narrow gauge mine rail system. One of the branch lines of this mine rail system runs through the mountain into the Kumgol-tong 1 valley where it terminates in a tailings pile. Two long-distance conveyor belt systems extend from the rail systems terminal to the east, across the Puktae-chon, to the Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory. Rail movements in the mine rail systems yards suggest that the mine is active but at a low level.

On the east bank of the Puktae-chon is the town of Kumgol. This is the largest town in the valley and likely serves as the headquarters and support base for all mining in the area. The most notable facilities located here are the Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory, Kumgol rail station, Kumgol rail classification yard and a series of long-distance conveyor belts that feed the clinker factor and rail loading and unloading facilities.

Located approximately 2 kilometers southeast of Kumgol, is a large mining facility identified as the Komdok (Kumgol) No. 3 Mine. It is connected to the Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory and Kumgol rail facilities by an approximately 3-kilometer-long conveyor belt system.

Ore extracted from the mines around Ryongyang and Kumgol areas is initially crushed, screened and stored at the mines and then either processed at the Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory or shipped by rail to the Tanchon where it is further processed at the Tanchon Magnesia Factory, shipped by rail to the Songjin Refractory Plant in Kimchaek-si, Hambuk and elsewhere in the country, shipped by rail or sea to China or shipped by sea in bulk carriers to foreign customers.15

Among the processed magnesite products reportedly produced by the Ryongyang Magnesia Clinker Branch Factory are magnesia clinker (3 mm and 10 mm), electrocast magnesia clinker and light and hard burnt magnesia.16

Tanchon Magnesia Factory and Port of Tanchon

The Tanchon Magnesia Clinker Factory is known as “the nation’s powerful refractory producer.” It receives ore extracted from the Ryongyang Mine by rail and uses it to produce “dozens of kinds of quality magnesia products, especially magnesia clinker, light burned magnesia and electrocast magnesia clinker. It also pushes the second- and third-stage processing.” Reports also indicate that in association with the Ryongyang Mine and Taehng Youth Hero Mine that the Tanchon Magnesia Factory produces, or supplies products to produce “chipboard and wainscot on an industrial basis. They continue to develop a variety of fine fixtures and building materials including door, newel, flowerpot, desk, shuttering and prop by raising the quality of slightly burned magnesia chipboard. Among the processed products is the roller for conveyer belt which is made of by-products from the magnesia clinker production process.”

Other items produced with products from the Tanchon Magnesia Factory reportedly include “magnesia cement, light burned magnesia fertilizer, pulp and paper, medicines, and cosmetics.” It is also used in the steel industry, and it can be used for optical equipment, rocket nozzles, and reactors.

Aside from being used domestically the magnesite ore and products produced by the Ryongyang Mine are shipped by sea through the port of Tanchon in bulk carriers to foreign customers. The port was upgraded during 2012 to boost exports of magnesite, zinc and other mineral resources. This itself was reportedly to enable the port city of Tanchon [to] become the source of finance for the country’s broader policy line of pursuing both economic development and nuclear capacities.17

Timeline of Key Developments at Ryongyang Mine

Early 2016 – Present | Ryongyang Mine Magnesite Production Rate Recovered.18

By early 2016 North Korean media was reporting that the “Taehung Youth Hero Mine and Ryongyang and Paekbawi mines were daily producing several hundred more tons of magnesite than scheduled.”

Small infrastructure and production improvements at the Ryongyang mine continued to be reported throughout 2017-2018. During September 2017 Minju Joson reported that the Ryongyang Mine “…manufactured and installed an optical ore sorter in the magnesite ore-dressing process to improve ore quality and “open up prospects for the CNC-ification and robotization.” During June 2018 Naenara reported that the mine had continued to introduce new processes and expanded computerization efforts. All these developments reportedly raised the “…mineral output 1.2 times as compared with the same period of last year” and “boosted the production of quality light-burned magnesia and magnesia clinker.”

During February 2019 it was reported that ore production at the Ryongyang Mine “…has increased by more than 20,000 tons from the same period last year.”

More recently, expressing the importance of the magnesia industry to the North Korean economy, Kim Jong-un during his April 12, 2019 speech before the 14th Supreme People’s Assembly stated, “We must improve the sectoral structure of the people’s economy, develop all sectors harmoniously, and secure world-class competitiveness in the magnesia industry and the graphite industry.”

2012 Through 2015 | Recovery from Typhoon Bolaven’s Extensive Damage.19

Operations at the Ryongyang Mine were severely disrupted during late-2012 when Typhoon Bolaven (known locally as Typhoon-15) made landfall in North Korea. The damage caused by flooding and mud slides was extensive. Korean people’s Army (KPA) troops were brought into the area to assist with the restoration of the mine and its supporting facilities. Among their many restoration activities during September were the, “…repairing pits and machines and equipment and removing heaps of muck and mud. [Clearing] debris and mud piled up inside Kumgol Railway Station. The first-stage pumping station of the third dressing plant and pumping stations of the second dressing plant have been recovered and drainage operation is at its height. The repair branch of the complex resumed the operation of the induction furnace, ensuring the production of parts for the repair and maintenance of damaged equipment. [Removing mud and debris] on the road extending more than 4 km in districts Nos. 2 and 3, helping resume the traffic. The Ryongyang Mine has fired up three light burning furnaces.”

Repairs continued through at least late-November when it was reported that the final stages of restoration had begun and that at the “…Ryongyang Mine finished repair and maintenance of excavators, electric cars and mine cars that were severely destroyed by landslide. The mine also repaired electric car lines and fired up light burning kilns.” The restoration of full production capacity likely took several years as indicated by the production output noted in the Mineral Commodity Summaries for 2013-2015.

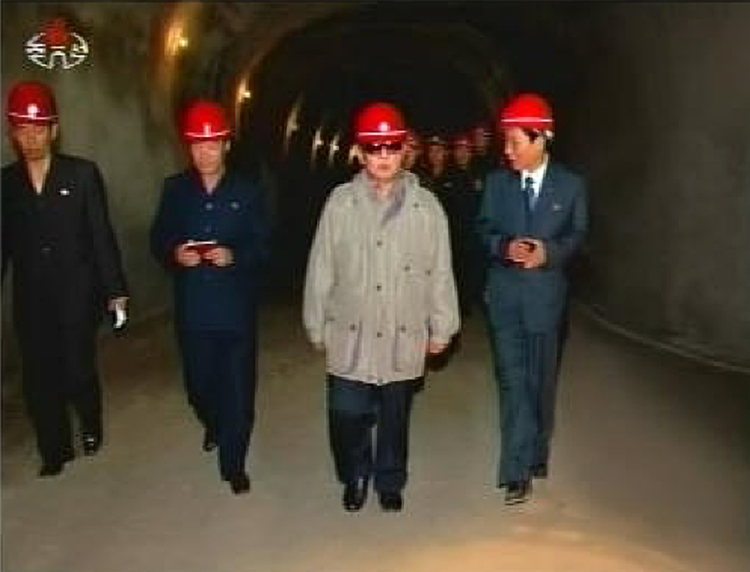

Fall 2011 | High-Level Visits from North Korean Leadership.20

Kim Jong-il made his third visit to the Ryongyang Mine to provide “field guidance” and encourage the workers to higher production on October 16, 2011. He visited various facilities of the mine and descended into a working mine shaft. He was accompanied by Kim Kyong Hui, member of the Political Bureau and department director of the WPK Central Committee, Jang Song Thaek, alternate member of the Political Bureau of the C.C., the WPK, and vice-chairman of the NDC, Pak To Chun, alternate member of the Political Bureau and secretary of the C.C., the WPK, Kwak Pom Gi, chief secretary of the South Hamgyong Provincial Committee of the WPK, and Ri Jae Il and Pak Pong Ju, first vice department directors of the C.C., the WPK. Kim Jong-il expressed the importance of the magnesite industry to the nation’s economy, “He once again expressed great satisfaction over the laudable feats performed by the workers of the above-said industrial establishments and the Taehung and Ryongyang mines in their endeavors to make a breakthrough toward the fulfillment of their national economy plans and consolidate the nation’s economic foundation.”

Kim Jong-il’s visit was followed less than one month later by a visit from North Korean premier Choe Yong Rim to the Tanchon Area Associated Mining Bureau, Taehung Youth Hero Mine, Ryongyang Mine, Tanchon Magnesia Factory, and Tanchon Smeltery on November 10, 2011. He provided “on-the-spot” guidance and “took measures for the increased production capacities of the relevant units.”

2010 Through 2011 | Work to improve output at the Ryongyang Mine in 2010 and 2011.21

During 2010 the Kumsan and Youth Pits converted their cutting sites into large-sized stopes to raise the production by a reported 50 percent higher than 2009 and a ring road was constructed to connect large cutting faces and the ore-unloading facility at the Kumsan Pit was rebuilt. Work also continued on the No. 2 and 3 cutting faces of the June 5 Pit. Just a few months later, during February, it was reported that the Ryongyang Mine had built more than ten new large mining sites and had implemented a “scientific business strategy” that was responsible for “trebling ore storing and processing capacity as compared with that in the past.” Throughout the remainder of 2011 North Korean media continued to report on additional developments at the mine and on praise bestowed upon it by Kim Jong-il.

1961 – 2009 | High-Level Visits to Ryongyang Mine.22

Kim Jong-il made his second visit to Ryongyang mine on May 21, 2009. He was accompianed by Kim Kinam, Jang Sung-taek, and Park Nam-gi. During the visit Kim entered the June 5th Pit and provided guidance.

In September 2003, Kim Jong-il made his first visit to Ryongyang mine for the opening of June 5th Pit. Ryu Hyun-sik and Han Sung-ryong joined him for the visit.

In April 1961, Apr 1961 President Kim Il-sung visited Ryongyang mine and names the nearby mountain, which is rich in magnesite deposits, Paekkumsan (i.e., magnesite mountain)”, saying the mountains in this area are all “gold mountains.” Since then, magnesite has been likened to “white gold” by the locals.

References

- For example, Cho Kyewan. Immense Underground Mineral ResourcesValue Comparable to that of Samsung and Hyundai, Hankyoreh, May 02, 2018, http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/PRINT/842906.html; Mollman, Steve. North Korea is sitting on trillions of dollars of untapped wealth, and its neighbors want in, QZ.com, June 15, 2017, accessed June 1, 2019, https://qz.com/1004330/north-korea-is-sitting-on-trillions-of-dollars-on-untapped-wealth-and-its-neighbors-want-a-piece-of-it/; Underground resources in North Korea, Magnesite, which accounts for half of the world’s reserves, NK Today, March 25, 2014, http://nktoday.kr/?p=2172; and Inter-Korean coal mine projects suspended during Lee administration, Hankyoreh, April 25, 2011, http://english.hani.co.kr/arti/english_edition/e_northkorea/474670.html. ↩

- For example, see: N. Koreas mineral resources estimated at US$3.3 tln: report, Yonhap, October 10, 2018, http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/search1/2603000000.html?cid=AEN20181011004600320; Heo Jung-won. How much natural resources does North Korea have?…6 billion tons of white gold, JoongAng Ilbo, August 15, 2018, https://news.joins.com/article/22886505 http://www.tongilnews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=23188; and Underground resources in North Korea, Magnesite, which accounts for half of the world’s reserves, NK Today, March 25, 2014, http://nktoday.kr/?p=2172. ↩

- Quan Zhenan and Li Gengqian. North Korean Mineral Resources: Rich Reserves, Weak Development, and Great Potential for Cooperation, Shijie Zhishi, September 2018, pp. 25-27; Development of slightly burnt magnesia products encouraged, Pyongyang Times, May 28, 2018, https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1532001303-127635182/Development-of-slightly-burnt-magnesia-products-encouraged/; and Underground resources in North Korea, Magnesite, which accounts for half of the world’s reserves, NK Today, March 25, 2014, http://nktoday.kr/?p=2172. For its part North Korea media always describes its magnesite reserves and production in glowing terms describing the mines and factories in the Tanchon area as having inexhaustible magnesite resources, annually extract millions of tons of minerals, flourishing mines, etc. ↩

- Increasing productivity of Ryongyang Mine, Ryomyong, February 19, 2019. http://www.ryomyong.com/index.php?page=north&no=35614; Seoul eyes untapped mineral resources in N. Korea, Yonhap, October 24, 2018. http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/search1/2603000000.html?cid=AEN20181024007500320; N. Korea’s mineral resources estimated at US$3.3tln: report, Yonhap, October 10, 2018. http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/search1/2603000000.html?cid=AEN20181011004600320; Quan Zhenan and Li Gengqian. North Korean Mineral Resources: Rich Reserves, Weak Development, and Great Potential for Cooperation, Shijie Zhishi, September 2018. pp. 25-27; Ryongyang Mine, Naenara, June 28, 2018. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1530230435-433545815/ryongyang-mine; Enormous North Korean underground resource like having Samsung-Hyundai buried underground, Hankyoreh, May 2, 2018. http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/economy/economy_general/842906.html; Nonferrous Ore Production Goes Up in DPRK, KCNA, April 18, 2016. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1546388148-557790342/Nonferrous-Ore-Production-Goes-Up-in-DPRK/; Area has Bright Prospect for Magnesite Products, Pyongyang Times, April 17, 2018. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1532001660-334105039/area-has-bright-prospect-for-magnesite-products/; Underground resources in North Korea, Magnesite, which accounts for half of the world’s reserves, NK Today, March 25, 2014. http://nktoday.kr/?p=2172; Two Koreas to conduct on-site survey of three mines in the North, Yonhap, July 27, 2007. https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20070727007200315; and Jung, Sang-yong. North Korean Magnesia Clinkers Popular Internationally, Yonhap, September 23, 2002. http://www.tongilnews.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=23188. ↩

- Locations of Rare Earth Minerals Reserves in North Korea, JoongAng Ilbo, May 23, 2019. https://news.joins.com/article/23476628; Quan Zhenan and Li Gengqian. North Korean Mineral Resources: Rich Reserves, Weak Development, and Great Potential for Cooperation, Shijie Zhishi, September 2018. pp. 25-27.; and Special Series on North Koreas Underground Reserves: Half of the Worlds Magnesite Reserves, NK Today, March 35, 2014. http://nktoday.kr/?p=2172. ↩

- Additionally, there is the Chngjin Refractory Factory in Chngjin-si, Hambuk Province. ↩

- Kay, Amanda. What is Magnesite? Investing News Network, August 8, 2018. https://investingnews.com/daily/resource-investing/critical-metals-investing/magnesium-investing/magnesite-magnesia-mgx-minerals-globex-mining/; and Underground resources in North Korea, Magnesite, which accounts for half of the world’s reserves, NK Today, March 25, 2014. http://nktoday.kr/?p=2172. ↩

- Quan Zhenan and Li Gengqian. North Korean Mineral Resources: Rich Reserves, Weak Development, and Great Potential for Cooperation, Shijie Zhishi, September 2018. pp. 25-27; Ryongyang Mine, Naenara, June 28, 2018. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1530230435-433545815/ryongyang-mine/; Area has Bright Prospect for Magnesite Products, Pyongyang Times, April 17, 2018. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1532001660-334105039/area-has-bright-prospect-for-magnesite-products/; Kim Jong-il visits economic sites across the country, North Korean Economy Watch, October 27, 2011. http://www.nkeconwatch.com/2011/10/27/kim-jong-il-visits-economic-sites-across-the-country/; Digging North Korea Out of a Hole, Daily NK, October 17, 2011. https://www.dailynk.com/english/digging-north-korea-out-of-a-hole/; Kim Jong Il Gives Field Guidance to Taehung Youth Hero Mine and Ryongyang Mine, KCNA, October 13, 2011. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201110/news15/20111015-37ee.html; Ryongyang Mine Takes on New Look, KCNA, June 16, 2011, http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201106/news16/20110616-22ee.html; Cutting Faces Made Large at Ryongyang Mine, KCNA, December 29, 2010. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2010/201012/news29/20101229-10ee.html; Cutting Faces Made Large at Ryongyang Mine, KCNA, December 29, 2010. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2010/201012/news29/20101229-10ee.html; and North Korea Handbook, (London: Yonhap), 2002. p. 1111-1112. ↩

- The Ryongyang mine has also been a number of awards or honorific titles over the years including, Order of Kim Il-sung, 20th Anniversary Mine and Double Chollima Mine. (Dancheon Ryongyang Mine), North Korean Human Geography. http://www.cybernk.net/infoText/InfoHumanCultureDetail.aspx?mc=CC0303&sc=A32020002&tid=CC020300008112&direct=1 ↩

- North Korea Handbook, (London: Yonhap), 2002, p. 1111-1112; and Foreign Trade of the DPRK 18-01, Foreign Trade of the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea (Electronic Edition), January 1, 2018. The Korea Magnesia Clinker Industry Group is reportedly located in the Pothonggang District of Pyongyang (email: kmcig@silibank.net.kp). ↩

- While some of the information used in the preparation of this study may eventually prove to be incomplete or incorrect, it is hoped that it provides a new and unique open-source look into the subject that others may build on. ↩

- Among the many sources used to assemble this listing are: North Korea Human Geography, Tanchn Ryngyang Mine, http://www.cybernk.net/infoText/InfoHumanCultureDetail.aspx?mc=CC0303&sc=A32020002&tid=CC020300008112&direct=1; Quan Zhenan and Li Gengqian. North Korean Mineral Resources: Rich Reserves, Weak Development, and Great Potential for Cooperation, Shijie Zhishi, September 2018. pp. 25-27; Ryongyang Mine, Naenara, June 28, 2018. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1530230435-433545815/ryongyang-mine/; Area has Bright Prospect for Magnesite Products, Pyongyang Times, April 17, 2018. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1532001660-334105039/area-has-bright-prospect-for-magnesite-products/; Kim Jong-il visits economic sites across the country, North Korean Economy Watch, October 27, 2011. http://www.nkeconwatch.com/2011/10/27/kim-jong-il-visits-economic-sites-across-the-country/; Youth mine sings change, Rodong Sinmun, January 7, 2015. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1450696780-66397652/–/; Special Series on North Korea’s Underground Reserves: Half of the Worlds Magnesite Reserves, NK Today, March 35, 2014. http://nktoday.kr/?p=2172; Digging North Korea Out of a Hole, Daily NK, October 17, 2011. https://www.dailynk.com/english/digging-north-korea-out-of-a-hole/; Kim Jong Il Gives Field Guidance to Major Industrial Establishments in Hamhung City, KCNA, October 16, 2011. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201110/news16/20111016-26ee.html; Kim Jong Il Gives Field Guidance to Taehung Youth Hero Mine and Ryongyang Mine, KCNA, October 13, 2011. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201110/news15/20111015-37ee.html; Ryongyang Mine Takes on New Look, KCNA, June 16, 2011. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201106/news16/20110616-22ee.html; Mines Alive with Drive for Great Surge, KCNA, February 2, 2011. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201102/news12/20110212-12ee.html; Cutting Faces Made Large at Ryongyang Mine, KCNA, December 29, 2010. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2010/201012/news29/20101229-10ee.html; and North Korea Handbook, (London: Yonhap), 2002. p. 1111-1112. ↩

- It is unclear, but this institution may also be known as the Ryngyang University of Industry. ↩

- There are a number of towns the Tanchn-gun area with the name Kmgol-tong. To facilitate specific identification official sources append a number to the location name. ↩

- Quan Zhenan and Li Gengqian. North Korean Mineral Resources: Rich Reserves, Weak Development, and Great Potential for Cooperation, Shijie Zhishi, September 2018, pp. 25-27. ↩

- Ryongyang Mine, Naenara, June 28, 2018, https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1530230435-433545815/ryongyang-mine/; and Development of slightly burnt magnesia products encouraged, Pyongyang Times, May 28, 2018, https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1532001303-127635182/Development-of-slightly-burnt-magnesia-products-encouraged/ ↩

- Quan Zhenan and Li Gengqian. North Korean Mineral Resources: Rich Reserves, Weak Development, and Great Potential for Cooperation, Shijie Zhishi, September 2018, pp. 25-27; N. Korea aims to develop resource-rich Tanchon, Yonhap, April 25, 2013, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20130425006800315; and Tanchon Port reconstruction completed, North Korea Economic Watch, April 25, 2013, http://www.nkeconwatch.com/2013/04/25/tanchon-port-reconstruction-to-be-completed-by-2012/. ↩

- “Nonferrous Ore Production Goes Up in DPRK,” KCNA, April 18, 2016. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1546388148-557790342/Nonferrous-Ore-Production-Goes-Up-in-DPRK/., “Large-scale mining, in final stages of modernization,”, Rodong Sinmun, July 8, 2017. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1530453777-51614644/%EC%B1%84%EA%B5%B4%EC%9D%98-%EB%8C%80%ED%98%95%ED%99%94-%ED%98%84%EB%8C%80%ED%99%94%EA%B3%B5%EC%82%AC-%EB%A7%88%EA%B0%90%EB%8B%A8%EA%B3%84/ , “Production Increases in Tanchon Area,” DPRK Today, August 30, 2018. http://dprktoday.com/index.php., “Ryongyang Mine,” Naenara, June 28, 2018. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1530230435-433545815/ryongyang-mine/., “Area has Bright Prospect for Magnesite Products,” Pyongyang Times, April 17, 2018. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1532001660-334105039/area-has-bright-prospect-for-magnesite-products/., “Increasing productivity of Ryongyang Mine,” Ryomyong, February 19, 2019. http://www.ryomyong.com/index.php?page=north&no=35614., “North Korea’s Kim Jong-un, Speech at Supreme People’s Assembly, Part 1,” Yonhap, April 13, 2019. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20190413020900504?input=fb&fbclid=IwAR2xRfnnZHAD6Ru8kJCeNWD9b0lCPuy6rDFHmya_YvUgbCFvwXwO_8dB3P8. ↩

- “Typhoon Brings Strong Wind, Storm Wave, Torrential Rain to DPRK,” KCNA, August 28, 2012; “Western Areas of DPRK Suffer from Typhoon-15,” KCNA, August 28, 2012; “Typhoon-15 Hits Most Areas of Korea,” KCNA, August 28, 2012; and “Korea Now in Radius of Typhoon,” KCNA, August 28, 2012., “Work to Clear Aftermath of Typhoon-15 Stepped Up in Komdok Mining Complex,” KCNA, September 8, 2012. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1451900140-571819620/Work-to-Clear-Aftermath-of-Typhoon-15-Stepped-Up-in-Komdok-Mining-Complex/., “Rehabilitation Project of Komdok Area Completed,” KCNA, November 27, 2012. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1451900305-280425184/Rehabilitation-Project-of-Komdok-Area-Completed/., Mineral Commodity Summaries 2000-2019, (Reston: U.S. Geological Survey) https://doi.org/10.3133/70202434. ↩

- “Light-Burned Magnesia Production Process Newly Established,” KCNA, November 17, 2017 http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201110/news15/20111015-37ee.html; “Kim Jong Il Gives Field Guidance to Taehung Youth Hero Mine and Ryongyang Mine,” KCNA, November 13, 2011., “Kim Jong-il visits economic sites across the country,” North Korean Economy Watch, October 27, 2011. http://www.nkeconwatch.com/2011/10/27/kim-jong-il-visits-economic-sites-across-the-country/; “Digging North Korea Out of a Hole,” Daily NK, October 17, 2011. https://www.dailynk.com/english/digging-north-korea-out-of-a-hole/; “DPRK Premier Goes around Tanchon Area,” KCNA, November 13, 2011. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201111/news13/20111113-22ee.html. ↩

- “Cutting Faces Made Large at Ryongyang Mine,” KCNA, December 29, 2010. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2010/201012/news29/20101229-10ee.html; “Mines Alive with Drive for Great Surge,” KCNA, February 2, 2011. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201102/news12/20110212-12ee.html; “Youth mine sings change,” Rodong Sinmun, January 7, 2015. https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1450696780-66397652/%EC%A0%84%EB%B3%80%EC%9D%84-%EB%85%B8%EB%9E%98%ED%95%98%EB%8A%94-%EC%B2%AD%EC%B6%98%EA%B4%91%EC%82%B0/; “Ryongyang Mine Takes on New Look,” KCNA, June 16, 2011. http://kcna.co.jp/item/2011/201106/news16/20110616-22ee.html ↩

- “Area has Bright Prospect for Magnesite Products,” Pyongyang Times, April 17, 2018.https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1532001660-334105039/area-has-bright-prospect-for-magnesite-products/; Major figures in North Korea, (Seoul: Ministry of Unification), 2013. http://www.sonosa.or.kr/newsletter/201303/2013_people_list.pdf ↩