Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant

- The Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant is one of only two declared and known uranium concentrate plants in North Korea (Pyongsan Uranium Concentrate Plant at Pyongsan is the other).1

- This facility was used for Yellowcake production at least through the mid-1990s, and therefore would require inspection under any new U.S.-DPRK denuclearization declaration and agreement as it has not been subject to international inspection for over 25 years since IAEA visits to the site as part of the Full Scope Safeguards Agreement process in 1992.

- Some sources suggest that both the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant and the Pyongsan Uranium Concentrate Plant were among the “5 nuclear facilities” presented to Kim Jong-un by President Trump during the February 2019 Hanoi Summit.

- However, Pakchon’s utility to current North Korea nuclear operations is unclear as satellite imagery from 2002 to 2019 suggests the mine has been in caretaker status.

- If North Korea offered up this facility as one of the “5 nuclear facilities,” this would be consistent with a negotiating tactic of putting on the table elements of the program that the North doesn’t consider essential to core capabilities.

- Even if this facility is dormant, it will be a significant target of environmental cleanup as the toxic byproducts of processing uranium bearing ore into Yellowcake in the past will have contaminated the surrounding areas and rivers.

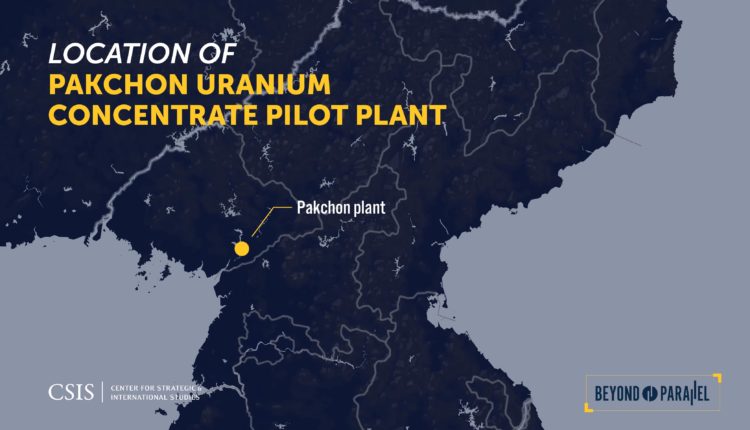

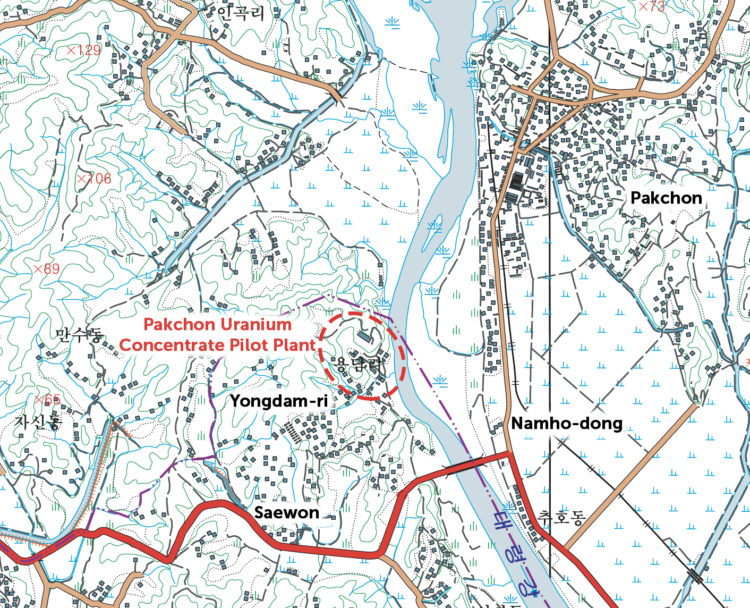

The Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant (39.710361 125.568141) is located in Pakchon (박천), Unjon-gun (Unjon County, 운전군), Pyongbuk (North Pyongyang Province, 평안북도).2 Specifically, 1.75 kilometers southwest of the center of Pakchon on a small hill above the Taeryong-gang (i.e., Taeryong River) and bordered by the small village of Yongdam-ri (용담리).3 This places it approximately 18 km southwest of the Yongbyon Nuclear Research Facility and approximately 77 km north-northwest of the capital Pyongyang. While the entire area encompassing the plant (e.g., main plant, housing farms, support buildings, orchards, etc.) totals approximately 38.7 hectares, the main processing plant building has a footprint of only 1.26 hectares.

The site chosen for the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant, like the nearby Yongbyon Nuclear Research Center, was well connected to the rest of the country via road and rail networks and, to a lesser degree, by air. The nation’s best highway connecting Sinuiju and Pyongyang passes through Pakchon. As does nation’s most important railroad line connecting the same two cities. The area was also well covered by North Korea’s national air defense system including the Korean People’s Air Force’s airbases at Taechon (approximately 22 kilometers north-northeast) and Kaechon (approximately 28 kilometers to the east).4 The entire Pakchon area is serviced by the same power grid that originates at the Supung hydroelectric powerplant and supplies the Yongbyon area.5 An electric power substation was built approximately 350 meters south of the main plant. While the plant was undoubtedly connected to the regional telephone network it is likely via buried service as no evidence of overhead service was identified in satellite imagery.

What would eventually become the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant was originally established by North Korea during the late-1950s or early-1960s to process graphite, phosphor, and rare earth minerals.6 Kim Tae-ho, a defector who worked at the plant, builds upon this understanding stating,

Initially, it was a factory built by the former Soviet Union to produce graphite used as decelerator material in a nuclear reactor. After the former Soviet Union withdrew, it began to operate as a plant producing refined uranium ore. The majority of the equipment was made in the Soviet Union.7

This, however, remains to be confirmed.

It was also during the 1960s that a Nuclear Research Institute was reportedly established in the Pakchon area.8 Subsequently, building upon earlier Japanese, Russian, and Chinese surveys, a region-wide mineral survey was undertaken during 1978 that confirmed a number of viable uranium bearing deposits. An internal Hungarian Foreign Ministry telegram from the Hungarian ambassador to North Korea, dated February 17, 1979 reveals that,

I heard from the Soviet ambassador that the DPRK has two important uranium quarries. In one of these two places, the uranium content of the ore is 0.26 percent, while in the other it is 0.086 percent.9

These developments, along with the start of construction on the 5MWe reactor at Yongbyon during 1979, led to the decision to convert the facility at Pakchon into a pilot uranium concentrate facility.10 The apparent intention was to both produce Yellowcake (U3O8, a mixture of uranium oxides) for use in the fuel rods of the new 5MWe reactor at Yongbyon and validate the concentrate process for a subsequent industrial-scale uranium concentrate plant to be built at Pyongsan (평산), Pyongsan-gun (Pyongsan County, 평산군), Hwangbuk (North Hwanghae Province, 황해북도).

As a result of its incorporation into the nuclear program, administrative control of the plant was transferred from the Ministry of Mining Industries to the Second Academy of Natural Sciences (SANS)—now the Academy of National Defense Science (ANDS), which was responsible for weapons research and development.11 Administrative control, however, is believed to have been with the Ministry of Atomic Energy Industry, which supervised all nuclear development projects.12 Consequently, the facility was also absorbed into the “Pungang District”—a common internal designation for the Yongbyon Nuclear Research Facility because it was built at the site of the village of Pungangni-nodongjagu (분강리노동자구).13 Because of the secrecy attached to the nuclear program, the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant was also assigned a cover designation of the “April Enterprise” (sometimes cited as the “April Business Enterprise”) by which it is commonly referred to by North Koreans.14

Operations at Pakchon reportedly began during 1982 with the feedstock uranium ore reportedly being acquired from mines in the Sonchon and Pakchon areas.15 According to Kim Tae-ho the ore received at the plant came from the Sonchon mine and was called “Ore No. 2” and the production target for uranium oxide concentrate production at the plant was one ton a month.16 Subsequently, the plant is reported to have processed and refined approximately 210 tons of uranium bearing ore into an unknown amount of Yellowcake between 1982 and 1992, when it was inspected by the IAEA as part of the Full Scope Safeguards Agreement process.17 The IAEA, however, has not been able to visit the plant since then to validate production and has had to rely upon satellite imagery to continue to monitor the facility.18

Kim Tae-ho, the defector who worked at Pakchon, described the plant and working in it in his 2003 book,19

When one crosses the bridge over the Taeryong River, which runs between Pakchon County and Unjon County in North Pyongan Province, goes a little in the direction of Sinuiju, turns into the first road on the right, and walks for 10 minutes or so, one will a factory, surrounded by an electric fence and guarded by armed sentries. It is actually located in Tongsam-ri, Unjon County, but in terms of its administrative division, it belongs to Pungang District (Yongbyon nuclear facility). It is called the April Enterprise [Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant]…

The April Enterprise was divided into a metallurgy workshop, calcium workshop, transportation workshop, engineering workshop, 15 April Technology Innovation Shock Brigade, and so on. There was a labor section, in charge of personnel; radiation volume section, in charge of preventing harm from radiation; a production section which superintended the “normalization” of production, a uranium analysis room, accounting section, and so on.

In addition, security oversight officers and security personnel (police), in charge of maintaining peace and public safety, were always on duty. In addition, security troops were responsible for providing armed sentries…

The metallurgy workshop, which was the central plant in the April Enterprise, was built on the 40-degree slop of a hill. The uranium ore loading site, ore polishing work squad, waste water treatment work squad, deposit extracting work squad, precipitation work squad, cleaning work squad, and so on were lined up from the top down.

The experimental plant of Institute No. 501 was situated at the bottom.

Once in a while, yellow smoke spewed from the experimental plant. When that smoke traveled up, as if it swept up the 40-degree incline, and began to cover the metallurgy workshop, the workers there began to experience severe difficult breathing and unbearable pain.20

Yellowcake production at Pakchon plant is believed to have terminated during the mid-1990s (e.g., when the Pyongsan Uranium Concentrate Plant came online) and the facility moved into caretaker status.21 With the termination of Yellowcake production at Pakchon, the administration of the plant may have been transferred back to the Ministry of Mining Industries from the ANDS. If this occurred the facility is likely no longer considered to be a component of the “Pungang District.”

Satellite Imagery

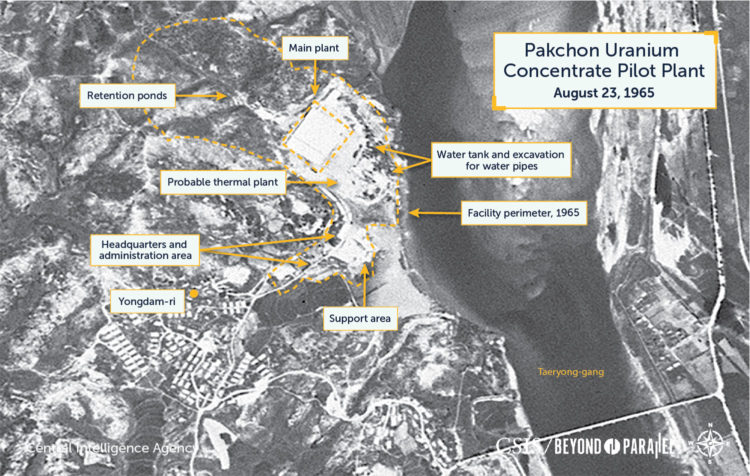

An approximately 2-meter resolution declassified CIA KH-4A satellite image from August 23, 1965 shows the facility as it looked 15 years before it was converted to uranium concentrate operations. The main plant is clearly visible, as are the headquarters and administrative area, several support buildings and the villages of Yongdam-ni and Saewon (새원).22 The villages likely provide housing for some of the workers and their families. Visible on the northeast side of the main plant is the excavation for the cistern pumping house and pipes that lifted water up from the Taeryong-gang to the main plant. While the early stages of a retention pond to the west of the plant is visible, it does not appear to be full and if there is a small earthen dam present it is not visible in the imagery. Due to the image’s low resolution it is unclear if the small retention ponds above are present. The support buildings on the south side, expanded headquarters and administrative area, support buildings, and fish farms to the south are not yet present.

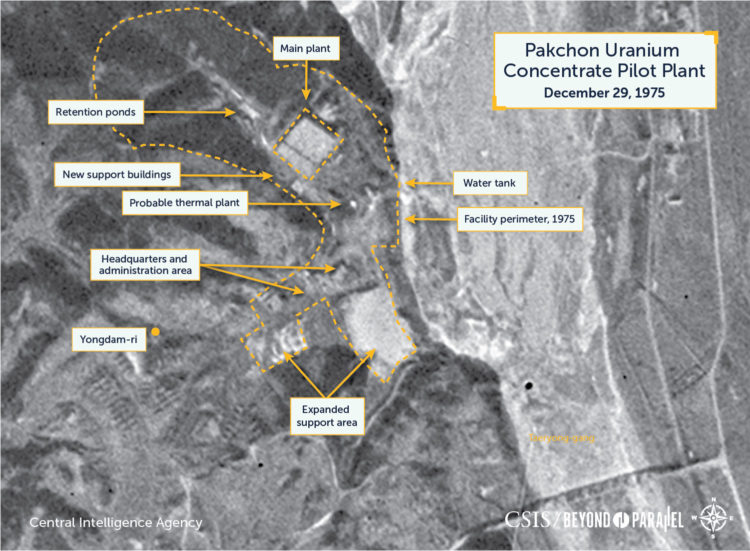

Ten years later, on December 29, 1975, an approximately 20-meter resolution declassified CIA KH-9 mapping camera image shows the facility has undergone some minor expansion. Several support buildings are now visible immediately to the south of the main plant, the headquarters and administrative area has expanded, and ground east of it appears to have been graded in preparation for the expansion of the support area. The retention pond to the west of the plant appears to have been slightly expanded.

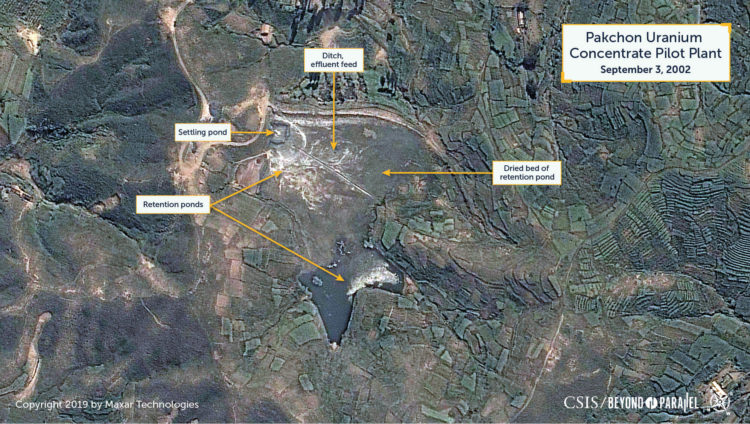

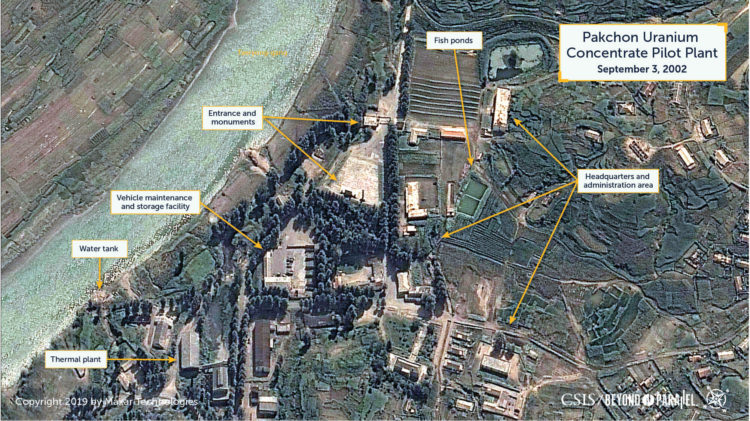

Although imagery from the 1980s and 1990s is not readily available it is apparent from a September 2, 2002 image that the facility had been significantly developed in the interim years with several support buildings now present just south of the main plant, several small support buildings distributed around the facility, and the expansion of the retention pond and an electric power substation approximately 350-meters south of the plant. Additionally, the remains (e.g., beams, girders, etc.) of two large buildings are present on northeast side of the main plant. The exact functions of many of the support buildings is unclear although at least one of these support buildings is likely to be a small thermal plant. The retention pond now covered approximately three hectares and was divided into two sections by an earthen dam. A trench—probably the waste feed from the main plant—bisected the eastern portion of the retention pond. Further south, the administration and support area had also been expanded with several support buildings, a small motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility with trucks present, a formal entrance with monuments was now present and small agricultural fields and two fish ponds added. All these changes indicated significant previous activity that was a result of the facility’s inclusion in the nuclear program as a pilot uranium concentrate plant.23 Taken as a whole, this level of activity indicates that the plant was being maintained in caretaker status and was not fully operational.

By 2008, the remains of the two large buildings on the north side of the plant had been razed and debris was spread across the ground. The retention pond, while three-quarters dry, had been further segmented with dykes. The western section was now divided into two parts, while the eastern section was now divided into four parts. An additional retention pond, encompassing .3 hectares, was constructed immediately west of the plant. This pond was partially full, and activity was observed around it and the larger retention pond. The administration and support area had also been developed with several support buildings and small greenhouses being added, the small motor vehicle maintenance and storage facility had trucks present and had been slightly expanded, and the agricultural fields were being maintained. This overall level of activity indicates that the plant remained in caretaker status but may have been used for small processing runs of iron-bearing ore of some type.

Satellite imagery indicates that the flooding that affected Pyongbuk (North Pyongyang Province) in both 2010 and 2012 did not damage the Pakchon Plant as it was high enough above the flood plain.24 Imagery from March 19, 2012, shows that four new smaller buildings were erected in the area of the razed support buildings. Two of these were located within a large earth-berm wall suggesting that they housed explosive materials of some sort. The large retention pond was dry with the exception of rainwater runoff, however, the small retention pond adjacent to the plant that now encompassed just .1 hectares, was full with a brick red colored liquid waste (suggesting a high oxidized iron content). Since there is no apparent drainage trail from the plant, it is probable that this effluent was pumped out of the plant. The reasons for this development are unclear as there are no indications that the plant was even intermittently operational. This overall activity observed suggests that the plant remained in caretaker status.

By 2014, all the retention ponds were essentially dry with the exception of rail water or melting snow runoff, several additional fish ponds were constructed, and several small greenhouses were replaced by a larger one. Imagery from 2015-2018, with one exception, show only minor changes (e.g., increase in the numbers of large greenhouses and fish ponds, roof maintenance, etc.) at the facility. The one exception was in an image from October 9, 2016 that shows that the small retention pond adjacent to the plant again contained a brick red waste. This was again apparent in an image from March 6, 2017, however, this time both the small retention pond and a second nearby pond both had the red sediment. Both ponds encompassed only 340 square meters each. Once again there was no apparent drainage trail from the plant indicating that this effluent was likely pumped out of the plant.

More recent imagery of the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant, acquired on April 23, 2019, show only minor changes have occurred during the past several years such as the erection of additional greenhouses, one of the small support buildings north of the main plant has been razed, the retention ponds remain dry with the exception of rain water runoff, etc.

Assessment

Taken as a whole, satellite imagery from September 2002 through April 2019 indicates that the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant has been in caretaker status the entire time. Satellite imagery, however, shows some minor inconclusive indicators (e.g., activity around retention ponds, small amounts of red effluent, etc.) of subsequent low-level activity. The most likely explanations for this activity would be small processing runs of iron-bearing ore of some type, caretaker maintenance work, or decommissioning of equipment within the plant. The observed activity is not indicative of continued uranium oxide production and there are no readily apparent indicators that the plant has processed uranium ore since September 2002.

Some sources occasionally discuss the potential to restore the facility to full Yellowcake production status. This is unlikely due both to the probable deterioration of the equipment within the main processing plant and support buildings during the past approximately 25 years (even with exceptional caretaker maintenance) and that the output from the Pyongsan Uranium Concentrate Plant, and potentially other such plants, is sufficient to meet current requirements. The remainder of the facility (e.g., entrances, monuments, roads, agricultural fields, etc.) are all actively being maintained and in good repair by North Korean standards. Personnel are often seen in the administration and support area and the vehicle maintenance and storage facility have varying numbers of trucks present in all imagery. Additionally, the housing and agricultural activities in and around the village of Yongdom-ni have grown slightly and appear to be in good condition indicating an active and reasonably sized population.

The processing of uranium bearing ore into Yellowcake produces toxic waste. Given reportedly poor, or non-existent, North Korean industrial health and safety practices it is likely that the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant represents an environmental risk to those in the immediate area and potentially downstream along the Taeryong-gang.

Research Note

This report is based upon an ongoing study of North Korea’s nuclear program and infrastructure begun by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., in 1988. Parts of this study were subsequently published by the author over the years.25 This study is based upon numerous interviews with government, defense and intelligence officials around the world, as well as declassified documents and open source reporting. Accuracy in any discussion of North Korea’s nuclear, biological, chemical, or ballistic missile programs is always a challenge and while some of the information used in the preparation of this study may eventually prove to be incomplete, or incorrect, it is hoped that it provides a new and unique look into the subject. The information presented here supersedes or updates these and other previous works by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. on these subjects.

References

- Among the sources consulted in the preparation of this report were: Author interview data; Melissa Hanham, et al., “Monitoring Uranium Mining and Milling in China and North Korea through Remote Sensing Imagery,” CNS Occasional Paper (James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, October 2018), https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/op40-monitoring-uranium-mining-and-milling-in-china-and-north-korea-through-remote-sensing-imagery.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Overview of North Korea’s NBC Infrastructure,” 38North, June 2017, https://www.38north.org/wp-content/uploads/pdf/NKIP-Bermudez-Overview-of-NBC-061417.pdf; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Facility Analysis: Pakchon Pilot Uranium Concentrate Plant,” Jane’s Satellite Imagery Analysis, July 11, 2017, https://janes.ihs.com/SatelliteImageryAnalysis/Display/jsia0257-jsia; Jeffrey Lewis, “Recent Imagery Suggests Increased Uranium Production in North Korea, Probably for Expanding Nuclear Weapons Stockpile and Reactor Fuel,” 38North, August 12, 2015, https://www.38north.org/2015/08/jlewis081215/; Andrea Berger, “What lies beneath: North Korea’s uranium deposits,” NKNews, August 28, 2014; IAEA Board of Governors, “Application of Safeguards in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,: IAEA, GOV/2011/53-GC(55)/24, September 2, 2011, p. 7, https://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/IAEA_DPRK_2Sept2011.pdf; Melissa Hanham et al., “Monitoring Uranium Mining and Milling in China and North Korea through Remote Sensing Imagery,” CNS Occasional Paper (James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, October 2008), https://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/op40-monitoring-uranium-mining-and-milling-in-china-and-north-korea-through-remote-sensing-imagery.pdf; Evaluation of and Prospects for North Korea’s Military System, (Seoul: Korea Institute for Defense Analyses, July 25, 2006); Hong So’ng-p’yo, “North Korea’s Military Science and Technology,” Kunsa Nontan, April 29, 2005; Kim Tae-ho, “I Saw the Truth of the North Korean Nuclear Plant,” Tokuma Shoten (Tokyo: 2003), pp. 57-63; Yun Sang-ho, “DPRK Nuclear Development Plan Controversy: What Is the ‘Secret Program’ Acknowledged by North,” Dong-a Ilbo, October 17, 2002; North Korea Handbook (Armong: Yonhap/M.E. Sharpe, 2002), pp. 709-711; How Much Do You Know About NBC Weapons and Missiles? (Seoul: ROK Ministry of National Defense, December 10, 2001), pp 95-96; Kang Ch’ol-hwan, “Residents of Punggang, Yongbyon, Nulcear Weapons Development Mecca,” Chosun Ilbo, November 29, 2001; Osamu Eya, Great Illustrated Book of Kim Chong-il, (Tokyo: Shogakukan, June 2000), pp. 64-65; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “Exposing North Korea’s Secret Nuclear Infrastructure, Part II,” Jane’s Intelligence Review 11, no. 8 (August 1999): 41-45, https://ihsmarkit.com/products/janes-intelligence-review.html; “North Korea’s Nuclear Infrastructure,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, February 1994, pp. 74-79, https://ihsmarkit.com/products/janes-intelligence-review.htm; Yim Yong-son, Military Secrets (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 1997), pp. 9-14; Song Ui-ho, “Manpower in North Korea’s Nuclear Development Program: Its Personal Relationships, Training and Taboos,” Wolgan Chungang, March 1994, pp. 252-267; Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “North Korea’s Nuclear Infrastructure,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, February 1994, pp. 74-79; Status of Nuclear Energy Development in North Korea, (Seoul: Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, 1993); “Study Details DPRK’s Atomic Power Facilities,” Chosun Ilbo, December 8, 1993, p. 6; Im Young-gyu, Lee Jae-gi, Noh Byon-hwan and Chang She-young, Investigative Research Report on North Korea’s Science in Korean, (Seoul: Korea Radiological Preventive Science Society, December 1993), pp 249-408.; Valeriy Fedorovich Davydov, “The Challenge to International Security: North Korea and Nuclear Weapons,” Ekonomika, Politika, Ideologiya, No. 9 (September 1993): 18-30; “North Korean Logging Operations in Siberia to Stop Next Year – Uranium Ore Then Charged,” North Korea News, No. 694 (August 2, 1993): 5; and “North Korea’s Nuclear Development, What Level is it at?,” Dong-a Ilbo, June 11, 1992; “Nuclear Plant Construction in Yongbyon and Pakchon, North Korea,” Hankyoreh, December 18, 1991; and “Nuclear Facility Confirmed in Pakchon, North Korea,” Kyunghyang Sinmun, October 29, 1991. ↩

- Transliteration of Korean place names into English always presents a challenge and among the more common alternate name spellings for Pakchon are: Pakchon, Pakch’on and Pakch’o’n, Additionally, the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant is sometimes identified in English as a “uranium purification plant,” “uranium refinement factory,” “uranium refining factory” or “uranium milling factory.” ↩

- Some older maps place Yongdam-ri (용담리) slightly further south and identify the village around the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant as Kujin (구진). ↩

- The Taechon Airbase houses an An-2 transport regiment and the Kaechon Airbase houses a MiG-19 regiment. ↩

- Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., “North Korea’s Nuclear Infrastructure,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, February 1994, pp. 74-79. ↩

- Author interview data; Im Young-gyu, Lee Jae-gi, Noh Byon-hwan and Chang She-young, Investigative Research Report on North Korea’s Science in Korean, (Seoul: Korea Radiological Preventive Science Society, December 1993), pp 249-408.; Andrew Mack, “The Nuclear Crisis on the Korean Peninsula,” Asian Survey 33, no. 4 (April 1993): 339–59, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2645102; and “Nuclear Facility Confirmed in Pakchon, North Korea,” Kyunghyang Sinmun, October 29, 1991. ↩

- Kim Tae-ho, “I Saw the Truth of the North Korean Nuclear Plant,” Tokuma Shoten (Tokyo: 2003), pp. 57-63. ↩

- This Nuclear Research Institute is sometimes identified as the “Pakchon Branch Institute” or Pakchon Atomic Power Research Center. It is most often referred to as an underground facility. For example, see: Andrew Mack, “The Nuclear Crisis on the Korean Peninsula,” Asian Survey 33, no. 4 (April 1993): 339–59, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2645102; “Nuclear Facility Confirmed in Pakchon, North Korea,” Kyunghyang Shinmun, October 29, 1991; “Ko Yong-hwan, Former Interpreter for Kim Il-song and High-Ranking North Korean Diplomat, Speaks,” Seoul Sinmun, October 9, 1991, p. 5; “First Defection of North Korean Diplomat,” Kyunghyang Shinmun, September 14, 1991; and “North Defector Gives News Conference,” KBS-1, September 13, 1991. Although it is unknown whether it has any influence in the decision to repurpose the processing plant to uranium oxide production, the Pakchon area is also home to a Korean People’s Army Officer Training School and the Choi-hyun Officer School. Author interview data; and “Seoul calls off Team Spirit 92,” International Defense Review, January 1992, p. 12. ↩

- “Telegram, Embassy of Hungary in North Korea to the Hungarian Foreign Ministry,” February 17, 1979, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, MOL, XIX-J-1-j Korea, 1979, 81. doboz, 81-5, 001583/1979. Obtained and translated for NKIDP by Balazs Szalontai, https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/110133. ↩

- Author interview data; “North Korea’s Nuclear Development, What Level is it at?,” Dong-a Ilbo, June 11, 1992; “Nuclear Plant Construction in Yongbyon and Pakchon, North Korea,” Hankyoreh, December 18, 1991; and “Nuclear Facility Confirmed in Pakchon, North Korea,” Kyunghyang Shinmun, October 29, 1991. ↩

- During early 2016, North Korea restored the name of the Second Academy of Natural Sciences (SANS) back to its original name of the Academy of National Defense Science (ANDS). Author interview data; “N.K. renames agency handling weapons development,” March 20, 2017; and “DPRK Reportedly Earns $500 Million Annually in Arms Exports,” Chollian News Database Service, November 3, 1996. ↩

- “Energy Institute Reports Status of DPRK Nuclear Facilities,” Dong-a Ilbo, 8 July 1993, p. 2. ↩

- Pun’gangni-nodongjagu is often referred to more simply as Pun’gang-ni (분강리). Kang Ch’ol-hwan. “Residents of Punggang, Yongbyon, Nulcear Weapons Development Mecca,” Chosun Ilbo, November 29, 2001. ↩

- Alternate transliterations of the cover designation include “April Industrial Company” or “April Industrial Enterprise.” Author interview data; Cho Min and Kim Chin-ha, Chronicle of the North Korean Nuclear Issue 1955 – 2009, (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification) 2014, http://repo.kinu.or.kr/bitstream/2015.oak/2332/1/0001468021.pdf; and “Development at ‘Dangerous Point’,” Yonhap, May 9, 1994. ↩

- There is considerable confusion over the names and locations of the mines that supply uranium ore to the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant. The most often mentioned mines are the: Kujang, Pakchon, Sonchon, “Sunch’ŏn’s Wolbingsan Uranium Mine,” “Suncheon Mine,” “Wolbisan Uranium Mine” and Kujang. “Wolbisan Uranium Mine,” however, is the name provided to the IAEA by North Korea in 1992. While mines with these names have not yet been precisely located, Wŏlbong-san (Wŏlbong Mountain, 월봉산, 39.748889, 126.118889) is located between Sonchon and Kujang—approximately 47 kilometers east of Pakchon. A number of coal mines are located on the western slopes of Wŏlbong-san, north and northeast of the mining town of Swaemokch’am (39.741111, 126.0975). One or more of the mines at this location may be the referenced “Wolbisan Uranium Mine” given transliteration challenges between Korean and English. If so, it is likely that the rich deposits of coal mined here contain small amounts of uranium—as is the case at the Pyongsan mine—and that this is the source of uranium ore for the Pakchon Uranium Concentrate Pilot Plant. IAEA Board of Governors, “Application of Safeguards in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” IAEA, GOV/2011/53-GC(55)/24, September 2, 2011, p. 7, https://isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/IAEA_DPRK_2Sept2011.pdf. It is interesting to note that monazite, a thorium and uranium-bearing mineral, was excavated from the river banks and beds of the Ch’ŏngch’ŏn-gang (i.e., Ch’ŏngch’ŏn River) approximately 11 km south of Pakchon as far back as the Japanese colonial days. Author interview data; Shin Sung-taek, “The Seeds of North Korea’s Nuclear Development are the ‘Natural Uranium in North Korea’,” News Hankuk, December 26, 2006, http://www.newshankuk.com/news/content.asp?news_idx=20061226104359042150; Kim You-dong, “A Study on the Mine Development of North Korea and the Inter-Korean Mineral Resources Competition, Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources,” Korean Society of Economic and Environmental Geology 38, no. 2 (March 3, 2003), http://www.kseeg.org/journal/download_pdf.php?spage=197&volume=38&number=2; Cho Min and Kim Chin-ha, Chronicle of the North Korean Nuclear Issue 1955 – 2009, (Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification) 2014, http://repo.kinu.or.kr/bitstream/2015.oak/2332/1/0001468021.pdf; Yim Yong-son, Military Secrets, (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten), 1997, pp. 9-14; Song Ui-ho, “Manpower in North Korea’s Nuclear Development Program: Its Personal Relationships, Training and Taboos,” Wolgan Chungang, March 1994, pp. 252-267; “Energy Institute Reports Status of DPRK Nuclear Facilities,” Dong-a Ilbo, July 8, 1993, p. 2; and Im Young-gyu, Lee Jae-gi, Noh Byon-hwan and Chang She-young, Investigative Research Report on North Korea’s Science in Korean, (Seoul: Korea Radiological Preventive Science Society, December 1993), pp 249-408. ↩

- Kim Tae-ho, “I Saw the Truth of the North Korean Nuclear Plant,” Tokuma Shoten (Tokyo: 2003), pp. 57-63. ↩

- IAEA Board of Governors, “Application of Safeguards in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” IAEA, GOV/2011/53-GC(55)/24, September 2, 2011, p. 7. ↩

- See note 15. ↩

- It should be noted that, as is common with many defector accounts, Kim’s is somewhat dramatic and confuses some details although the overall description is generally accurate. ↩

- Kim Tae-ho, “I Saw the Truth of the North Korean Nuclear Plant,” Tokuma Shoten (Tokyo: 2003), pp. 57-63. ↩

- At least one source speculates that the facility was closed during 1992. Im Young-gyu, Lee Jae-gi, Noh Byon-hwan and Chang She-young, Investigative Research Report on North Korea’s Science in Korean, (Seoul: Korea Radiological Preventive Science Society, December 1993), pp 249-408. ↩

- Some older maps identify Saewon (새원) as Tongmul-li (동문리). ↩

- Some of these developments (e.g., the electric power substation, etc.) may have been present in the 1960s and 1970s. However, the resolution of the readily available imagery is not sufficient to identify them. ↩

- “North P’yongan Province Flood Damage Relief Work,” Korean Central Broadcasting Station, August 2, 2010; and “Recovery Work in North P’yongan Province After Flooding,” Korean Central Broadcasting Station, August 17, 2012. ↩

- “Exposing North Korea’s Secret Nuclear Infrastructure, Part I,” Jane’s Intelligence Review 11, no. 7 (July 1999): 36-41; “Exposing North Korea’s Secret Nuclear Infrastructure, Part II,” Jane’s Intelligence Review 11, no. 8 (August 1999): 41-45, https://ihsmarkit.com/products/janes-intelligence-review.html; “North Korea’s Nuclear Infrastructure,” Jane’s Intelligence Review, February 1994, pp. 74-79, https://ihsmarkit.com/products/janes-intelligence-review.htm; and more recently in “Facility Analysis: Pakchon Pilot Uranium Concentrate Plant,” Jane’s Satellite Imagery Analysis, July 11, 2017, https://janes.ihs.com/SatelliteImageryAnalysis/Display/jsia0257-jsia. ↩