Undeclared North Korea: The Kumchon-ni Missile Operating Base

Key Findings

- Located 1,100 kilometers west of Tokyo and 165 kilometers northeast of Seoul the Kumchon-ni undeclared ballistic missile operating base houses a battalion- or regiment-sized unit equipped with Hwasong-9 (Scud-ER) medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBM).1

- Media reports suggest that during wartime the 1,000-kilometer-range Hwasong-9 unit based at Kumchon-ni is tasked with striking targets in the southern half of Japan and, to a lesser degree, throughout South Korea.2

- Should the missile unit based at Kumchon-ni be equipped with more recently emerging MRBMs (e.g., Pukkuksong-2/KN-15, etc.) the threat envelop could include all of Japan, including U.S. military bases on Okinawa, and beyond.3

- This base is one of approximately 20 undeclared ballistic missile operating bases and one that is reported to be tasked with not only strikes against the southern half of Japan, but is also capable of striking all of South Korea.

- This is the first comprehensive public report detailing the development, organization, and threat posed by the Kumchon-ni missile operating base.

- North Korean missile operating bases would presumably have to be subject to declaration, verification, and dismantlement in any future final and fully verifiable denuclearization deal.

The Kumchon-ni (금천리) missile operating base is located within North Korea’s tactical missile belt, in Anbyon-gun (안변군, Anbyon County), Kangwon-do (강원도, Kangwon Province), 75 kilometers north of the DMZ, 165 kilometers northeast of Seoul—the capital of South Korea and 1,100 kilometers west-northwest of Tokyo.4 Although occasionally, and inaccurately, referred to as an “…underground missile storage…” facility it is a forward missile operating base subordinate to the Korean People’s Army (KPA) Strategic Force (the organization that is responsible for all ballistic missile units).5 It is one of the smaller missile operating bases and likely houses a battalion- or regiment-sized ballistic missile unit that during the early-1990s was reported to have been equipped with the 500-600-kilometer-range Hwasong-6 (Scud C) short-range ballistic missiles (SRBM). During 1999 it was confirmed that the unit based at Kumchon-ni was one of the first to be equipped with the then new 1,000-kilometer-range Hwasong-9 (Scud-ER) medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM).6 While the Hwasong-6 allowed the missile unit based at Kumchon-ni to strike at almost all of South Korea (with the exception of Cheju-do), the longer-range Hwasong-9 extended that threat envelop to being able to deliver a 750 kilogram warhead to all of South Korea and the southern half of Japan (e.g., Kyushu, Shikoku and a large portion of Honshu)—including many bases used by the U.S. military. Should the missile unit based at Kumchon-ni be equipped with more recently emerging MRBMs (e.g., Pukkuksong-2/KN-15, etc.) the threat envelop could include all of Japan, including U.S. military bases on Okinawa and beyond.7 Finally, the Kumchon-ni base facilities appear to provide logistical support and housing for the personnel that operate the nearby Hwangnyong-san early warning radar base.

Development

Construction of a ballistic missile operating base in the Kumchon-ni area is believed to have begun sometime during 1991-1993 using specialized engineering troops from KPA Unit No. 583 (the cover designator of the Military Construction Bureau).8 This was also the same time period during which construction was undertaken on the Sakkanmol and Kal-gol missile operating bases.9 This initial phase of construction appears to have included excavation of four underground facilities, construction of a drive-through missile support facility, and a modest collection of headquarters, administration, barracks, housing, and support structures.

On October 4, 1991 the director of the Agency for National Security Planning (today the National Intelligence Service), So Tong-kwon, stated in testimony before the National Assembly Defense Committee that during July 1991 North Korea conducted a training launch of a Hwasong-6 from “…a mobile launcher at a frontline base in Kangwon Province.”10 While this has generally been assumed to have been a reference to the Kal-gol missile operating base it now appears that it was conducted by the ballistic missile unit assigned to the Kumchon-ni missile operating base.11

Construction at Kumchon-ni proceeded slowly because of the demands that multiple projects placed upon the specialized construction engineering forces, the 1994 death of Kim Il-sung and the subsequent period of repeated drought, famine, and economic collapse—known collectively as the Arduous March. Occasional media reports during the mid-1990s to late-1990s appear to attest to the slow progress of construction activity at all the forward (south of a line running from Pyonyang to Wonsan) ballistic missile bases—including Kumchon-ni.12

By 1998, with the conditions of Arduous March abating, construction was reinvigorated and the following year some of the first public reports specifically mentioning construction at the forward ballistic missile operating bases (including Kumchon-ni) stated that these bases were equipped with the Hwasong-6.13 A declassified Defense Intelligence Agency report from April 1999, however, indicates that by 1999—and potentially as early as 1998—the KPA had begun deployment of the Hwasong-9 (Scud-ER) MRBM to the Kumchon-ni missile operating base,

North Korea continues efforts to extend the range of its SCUD missiles. The new 1,000 km extended-range SCUD is currently being fielded at Kumchon-ni, 75 km north of the DMZ. With range comparable to the No Dong, but cheaper to construct, the extended-range SCUD (also called SCUD-ER) can deliver at 750 kg warhead to western Japan from Kumchon-ni, or reach all of South Korea even from northern bases near the Chinese border. In addition to its increased capability, the SCUD-ER has proven cheaper to produce than the No Dong.14

Taken as a whole this declassified report and the open source reports suggest that a combination of Hwasong-5/-6 and Hwasong-9 missiles equipped the unit based at Kumchon-ni.

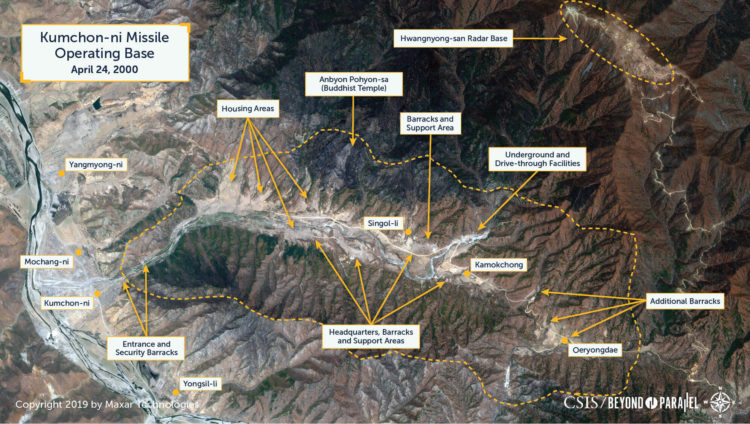

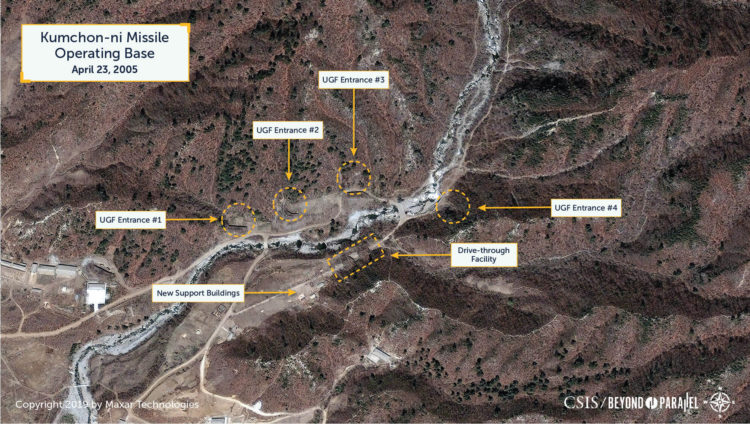

The earliest high-resolution commercial satellite imagery readily available of the Kumchon-ni area is from April 24, 2000 and indicates that the base was built in a narrow valley east of the town that encompassed the tiny agricultural hamlets of Singol-li (신곤리, 38.966111 127.594722), Kamokchong (가목정, 38.961111 127.602778), and Oeryongdae (외령대, 38.953151 127.620043).15 At this time the base consisted of a modest collection of headquarters, administration, underground facilities (UGF), missile support facility, barracks, housing, and support structures and it appeared to be near the end of a first-phase construction effort. Just discernable in this 2000 image are the entrances to four UGFs and the drive-through facility.

This assessment is supported by the South Korean Ministry of National Defense (MND) March 2001 annual report to the president in which, “Kumchon-ni, Anbyon-gun, Kangwon-do” is identified as one of several underground ballistic missile operating bases still under construction, but nearing completion.16 The following month Major General Pak Sung-chun, responsible for North Korean intelligence for the South Korean Joint Chiefs of Staff, reiterated these statements and added that the unit deployed at Kumchon-ni and other forward missile operating bases were equipped with Hwasong-5/-6 missiles.17 General Pak’s statement and the earlier Defense Intelligence Agency report continue to suggest that at least through 2001 a combination of Hwasong-5/-6 and Hwasong-9 missiles equipped the unit based at Kumchon-ni.

During 2002, the KPA reportedly conducted its first combined “Command Post Exercise (CPX)” with elements from both Hwasong-7 (Nodong) and Hwasong-5/-6/-9 (Scud B/-C/-ER) units. While unconfirmed, it is believed that the unit based at Kumchon-ni also participated in this and most subsequent exercises.18

Very little specific information on the Kumchon-ni ballistic missile operating base or the missile systems deployed here has appeared in the open source literature since the early 2000s. Most that has appeared has simply repeated that which was published previously.19 Satellite imagery, however, shows gradual development of the base over the years.

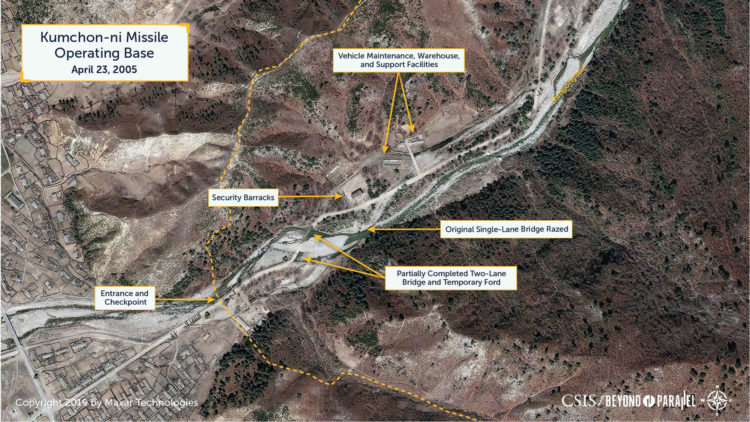

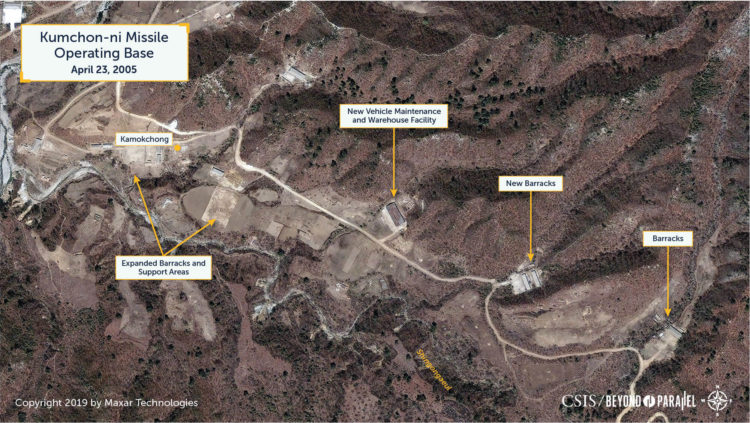

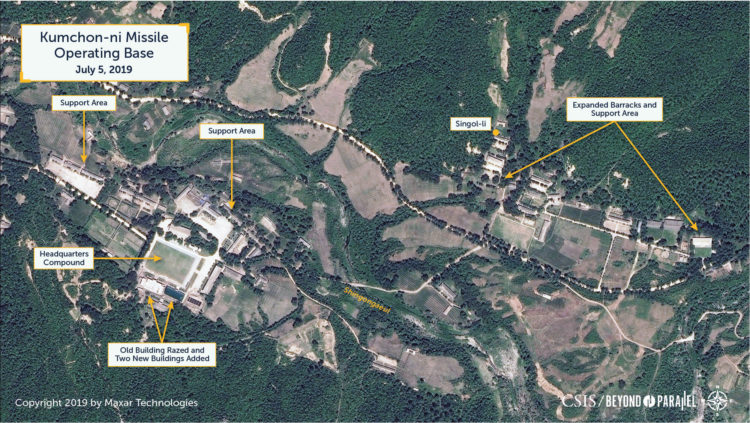

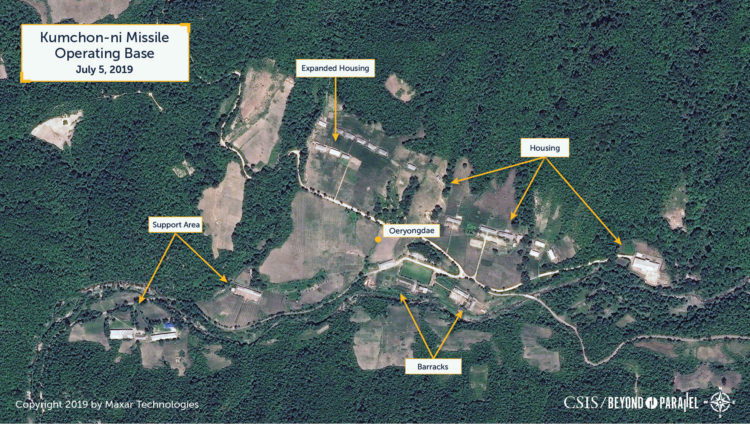

A high resolution 50-centimeter satellite image acquired on April 23, 2005 shows the base in good detail after the initial construction had been completed. It is also one of the few images that provides a clear view of the UGF entrances and the drive-through missile support facility. In this area several support buildings were built adjacent to the drive-through facility and the berm in front of UGF entrance has been partially washed away by the stream. Among the significant changes that had taken place elsewhere during the five years since 2000 were the construction of a new concrete two-lane bridge just east of the entrance to replace the original single-lane bridge, construction or expansion of a number of support buildings in the headquarters, barracks, and support areas, first-phase completion of the headquarters compound, expansion of the barracks and support area at Singol-li (신곤리, 38.966111 127.594722), construction of a vehicle maintenance, warehouse facility, and barracks in the Kamokchong area, and three barracks in the Kamokchong–Oeryongdae area to the east. These developments suggest that there was an increase in the number of personnel assigned to the base, the expansion of support units or a potential increase in the number, or change in the type of missile transporter-erector-launchers (TEL) or mobile-erector-launchers (MEL) deployed here—or any combination of these.

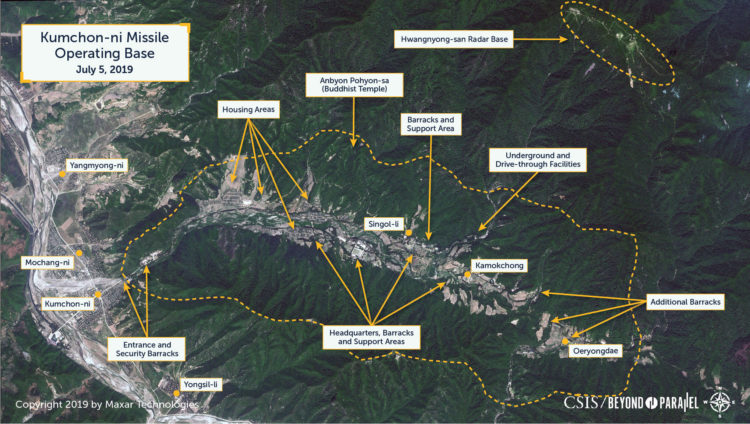

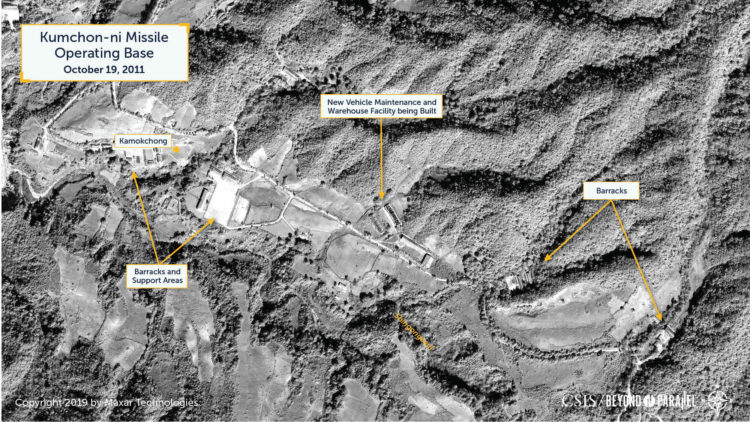

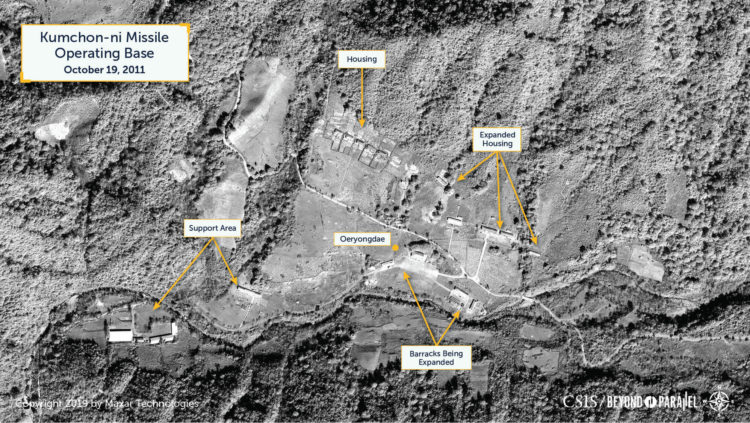

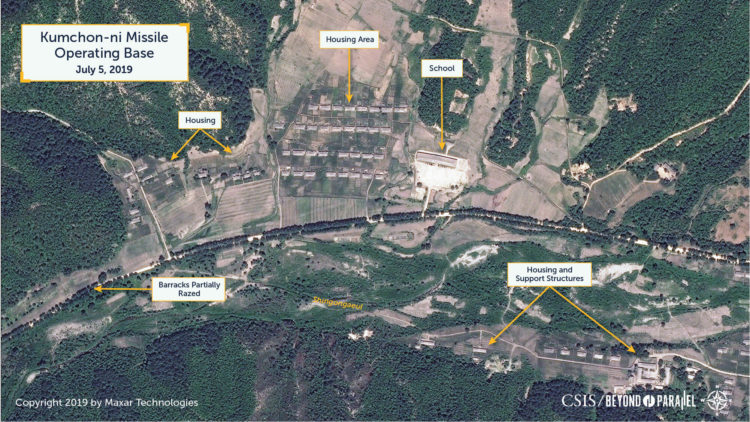

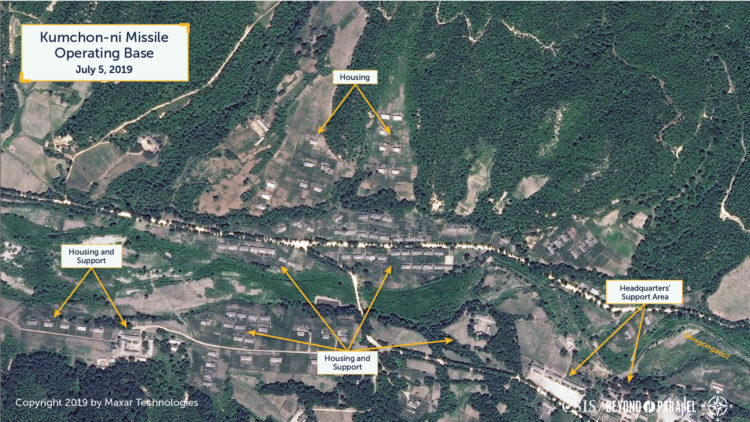

Satellite imagery from 2005 through 2010 indicates that a second-phase construction project was undertaken at Kumchon-ni that witnessed the expansion of the security headquarters and barracks and the vehicle, warehouse, and support facility adjacent to it (including the construction of two greenhouses), construction of a new housing area with 40+ units, a school and a support facility west of Singol-li, new monuments and a new building erected at the headquarters compound, construction of a barracks southeast of the headquarters compound, and the large building in the vehicle maintenance and warehouse facility at Kamokchong razed and replaced by two smaller buildings.20 With the end of this second phase of construction the base appears to have been complete.

During 2006 a number of training/test launches were conducted from the historical Kittae-ryong (깃대령) ballistic missile training facility also located in Anbyon-gun.21 It is believed that at least one was conducted by the missile unit based at the Kumchon-ni missile operating base.22

Following Kim Jong-un’s ascension to power in December 2011 he instituted widespread changes throughout the KPA emphasizing realistic training and increased operational readiness. These changes soon resulted in the reorganization of the Strategic Rocket Command into the Strategic Force during 2013 as well as significant infrastructure developments at a number of missile bases. At Kumchon-ni, these developments undoubtedly resulted in training and operational readiness improvements. Observations in satellite imagery from 2011-2016 show the construction of a number of fish farms and greenhouses distributed throughout the base and the rearrangement or expansion of several barracks and support areas. These developments were likely a result of Kim’s directives and intended to improve the quality of life of the missile troops based here.

Satellite imagery from 2017 to present continues to show minor infrastructure changes to the base that are consistent with what is often seen at remote KPA bases of all types. For example, several additional greenhouses were erected and a headquarters building constructed during 2005-2009 was razed and replaced by two new buildings during 2018-2019. As of August 2019, the base is active and being well-maintained by North Korean standards. All these developments attest to the ongoing importance of the Kumchon-ni missile operating base to the KPA and North Korean leadership.

Organization

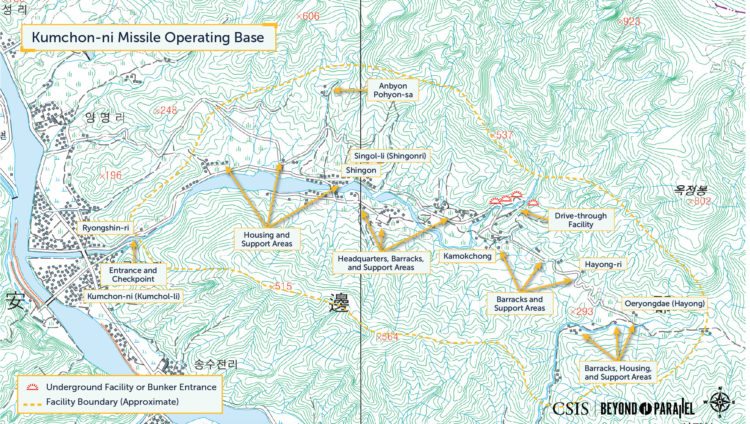

The Kumchon-ni missile operating base is located along both sides of a narrow, forked, valley east of Kumchon-ni (금천리, 38.958056 127.548889) from which it derives its name. The main base extends approximately 8.6 kilometers up the valley and encompasses approximately 16.4 square kilometers on the southern slopes of Hwangnyong-san (황룡산, Hwangnyong Mountain, 38.992778, 127.619444). Approximately 4.8 kilometers up the valley there is a small branch valley that runs north for approximately 1.4 kilometers where the base’s UGFs and drive-through missile support facility are located. With the construction of the base during the 1990s it absorbed the tiny agricultural hamlets of Singol-li, Kamokchong and Oeryongdae. Running down the center of the valley, and the base itself, is a small stream sometimes identified as the Shingongaeul (신곤개울, Shingon Creek), which is a tributary of the Chongjok-kang (정적강, Chongjok Stream) that runs through Kumchon-ni. Most of the area encompassed by the base consists of unoccupied mountains and small agricultural activities that support the base. It is unknown whether the military facilities and housing areas in the towns of Kumchon-ni or Samsong-ni (삼성리, 38.933056 127.593611) are associated with base.

The base can be functionally divided into four activities—agricultural support, housing, main base (including headquarters, barracks, vehicle maintenance, warehouse, and a variety of small support elements), and the underground and missile support facilities.

Small agricultural activities such as cultivated fields, greenhouses, and support buildings are dispersed throughout the facility, while housing (excluding barracks) is generally located in the western half of the base.23 Since 2011 there has been a steady increase in the number of greenhouses at the base. Only a small portion of the Kumchon-ni base facilities (potentially, only those in the area Oeryongdae area) are likely dedicated to providing logistical support and housing for the personnel that operate the nearby Hwangnyong-san early warning radar base.

The main base is located approximately 3.6 kilometers up the valley on the south side and consists of the headquarters compound, cultural/education hall, approximately a dozen small barracks and support buildings, greenhouses, barracks, and a parade ground. Additional support buildings are located both east and west of the headquarters compound.

Spread out along the branch valley on the north side of the base are entrances to four UGFs, the drive-through missile support facility, and several small support facilities. The UGFs are located on both sides of this valley in two groupings—three on the west side spaced approximately 120-150 meters apart and the fourth across the stream 175 meters to the east. Each entrance is 5 to 7-meters wide and secured by two outward opening doors. Approximately 15-18 meters in front of three of the entrances is a large rock and dirt berm built from the debris removed when excavating the UGFs. These berms are approximately 15-20 meters-high, 30-50 meters-long, and intended to protect the entrances from artillery fire and aerial attack. As with the other missile operating bases it is uncertain whether the adjacent UGF tunnels are internally connected so that vehicles (i.e., TEL/MELs, reload vehicles, etc.) can drive through them. At a minimum, and following typical KPA practices, some are likely linked by small internal connecting tunnels. The size of the entrances, as well as known KPA practices, suggests that these tunnels are capable of housing the unit’s TEL/MELs, reload vehicles, other technical vehicles, and supplies. Due to the UGF entrances’ location in a narrow tree-lined valley they are frequently difficult to identify in satellite imagery except in the late-fall or in winter after a snow fall.

The missile support facility—used for arming, fueling, and maintenance operations—is located on the south side of the branch valley across the stream opposite UGF entrance #3. It consists of a drive-through facility measuring approximately 95-meters-long overall with two approximately 20-by-12-meter earth-covered shelters separated by an open bay. In general appearance they appear closer to those found at the Sino-ri missile operating base rather than those at missile operating bases such as Sakkanmol or Sangnam-ni. It is unclear if there are additional entrances to UGFs within or adjacent to them, but neither would be unusual. As with the UGF entrances the vegetation on the drive-through facility and adjacent hillside make them extremely difficult to identify in satellite imagery.

Extremely little reliable open source information is available concerning the size of the missile unit based at Kumchon-ni. This information, when combined with the size and layout of the base, suggests that is it a battalion- or regiment-sized unit with a total of 4-6 TELs/MELs, a headquarters and organic support units—making it one of the smaller missile operating bases.24

Despite the strategic importance of all the KPA’s ballistic missile operating bases and concerns of either pre-emptive or wartime airstrikes against these facilities, there is only one readily visible fixed antiaircraft artillery (AAA) position within 10 km of the Kumchon-ni base.25 The base, however, is within the overlapping air defense umbrella of five SA-2 and two SA-5 surface-to-air missile (SAM) bases. Additionally, all KPA units of this size have some level of organic air defense elements equipped with both light AAA and shoulder fired SAMs (e.g., SA-7, SA-16, etc.). The presence of what appear to be several abandoned AAA positions at Kumchon-ni tends to support the presence of an organic air defense capability.

Located approximately 4.3 kilometers above and to the northeast of the base is the Hwangnyong-san early warning radar base (황룡산, 38.992778 127.619444). This radar base is accessed by the main road that runs through the Kumchon-ni base and then winds its way up to the mountain peak. The Hwangnyong-san base is part of Korean People’s Air and Anti-Air Force’s national early warning and air defense network and reports to the national control center in Pyongyang. The base is equipped with two P-80 BACK NET and two unidentified radars, all of which are mounted in underground hardened bunkers that allow the antennas to be elevated or retracted and covered by moveable concrete and steel blast doors.

Finally, located approximately one kilometer above the base on the north side of the valley is the historical Anbyon Pohyon-sa (Buddhist Temple).

Research Note

This report, as are the others in this series, is based upon an ongoing study of the Korean People’s Army ballistic missile infrastructure begun by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. in 1985. This study is based upon numerous interviews with North Korean defectors, government, defense, and intelligence officials around the world, as well as declassified documents and open source reporting. Accuracy in any discussion of North Korea’s nuclear, biological, chemical, or ballistic missile programs is always a challenge and while some of the information used in the preparation of this study may eventually prove to be incomplete, or incorrect, it is hoped that it provides a new and unique look into the subject. The information presented here supersedes or updates previous works by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. on these subjects.

Although over 41 high-resolution and medium-resolution satellite images were analyzed during the preparation of this report, the images ultimately presented in this report were purposely selected for their detailed or historical view of the structures and activities within and around the Kumchon-ni Missile Operating Base.

References

- The authors wish to thank Dana Kim, research assistant in the CSIS Korea Chair, and Heeu Millie Kim, a former intern in the CSIS Korea Chair, for their invaluable assistance in support of this project. ↩

- In addition to the sources noted below the following media reports provided some more generalized background used in the preparation of this report: “North’s Continued Military Buildup ‘No Surprise’,” Korea Herald, February 5, 1991, p. 8; “North Reportedly Expands Scud Unit,” Dong-A Ilbo, August 25, 1991, p. 2; “Newspaper Reports North’s Scud Missile Deployment,” Seoul Sinmun, February 24, 1992, p. 8; and “US Military Detects Underground Bases in DPRK,” NHK, December 8, 1998. ↩

- There are approximately fifteen bases used by U.S. forces in southern Japan and approximately 70% of USFJ facilities are concentrated in Okinawa. Defense of Japan (Annual White Paper) (Tokyo: Ministry of Defense, 2018), 35, mod.go.jp/e/publ/w_paper/pdf/2018/DOJ2018_Full_1130.pdf. ↩

- The transliteration of Korean place names into English is frequently challenging and often results in confusion and the Kumchon-ni missile operating base is no exception to this phenomenon. Among the alternative transliterations for Kumchon-ni are: Geumcheon-ri, Geumcheonri, Keumcheon-ri, Kumcheon-ri, Kumcheonri, Kŭmch’ŏl-li, Kumchon-ri. For consistency and ease of reading Kumchon-ni and other places, names used in this report are those accepted by the U.S. National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA).

The national designator for the missile operating base at Kumchon-ni is unknown and North Korea is not known to have ever made specific reference to its existence. The first reference to the use of the Kumchon-ni designation known to the author occurred in the early-1990s during the author’s conversations with defense and intelligence officials. Subsequently, during the late-1990s this designation began to appear in media reporting concerning North Korean missile facilities.

Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.; “ROK Weekly Views ROK-US ‘Perception Gap’ Toward DPRK Military,” Chugan Choson, April 10, 2001, No. 1648; “ROK Defense Ministry Claims DPRK Building Missile Power as World Debates US Plan,” JoongAng Ilbo, March 12, 2001, p. 2; and “ROK Daily Views DPRK Missile Buildup,” Kyonghyang Sinmun, March 4, 2001. ↩

- “Expansion of North Scud Missile Base,” JoongAng Ilbo, March 5, 2001, https://news.joins.com/article/4045601; and “North Korea, 3 Locations Along MDL Deployment Preparation,” Chosun Ilbo, September 29, 1999, http://news.chosun.com/svc/content_view/content_view.html?contid=1999092970058. ↩

- Some sources identify the Scud-ER as being a SRBM, however, the National Air and Space Intelligence Center and other sources identify it as a MRBM. National Air and Space Intelligence Center, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, (Wright-Patterson Air Force Base: National Air and Space Intelligence Center), NASIC-1031-0985-17, June 2017, p. 25. Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.; “ROK Weekly Views ROK-US ‘Perception Gap’ Toward DPRK Military,” Chugan Choson, April 10, 2001; “ROK Defense Ministry Claims DPRK Building Missile Power as World Debates US Plan,” JoongAng Ilbo, March 12, 2001, p. 2; and “ROK Daily Views DPRK Missile Buildup,” Kyonghyang Sinmun, March 4, 2001. ↩

- It is unlikely that the missile unit at Kumchon-ni would be equipped with the Nodong-1/-2 as production of these system appears to have been completed, almost all of these are already deployed to bases in the North’s strategic rear, and the Scud-ER is simpler and less expensive to construct than the Nodong. Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.; and A Primer on the Future Threat, The Decades Ahead: 1999-2020, (Washington, D.C.: Defense Intelligence Agency), July 4, 1999, pp. 79-80. ↩

- Physical construction may have begun somewhat earlier and deployment occurred during the 1991-1993 time period. Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.; “Expansion of North Scud Missile Base,” JoongAng Ilbo, March 5, 2001, https://news.joins.com/article/4045601; Kang Ho-sik. “North’s Missiles Increase. Strategic, Forward Deployment Both in and Out,” Kyunghyang Shinmun, March 5, 2001, https://www.bigkinds.or.kr/news/newsDetailView.do?newsId=01100101.20010305000000301; Osamu Eya, Great Illustrated Book of Kim Chong-il, (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 2000), pp. 10-15; “Defector Says Long-Range Missile Bases Built,” KBS-1, August 24, 1993; and “Newspaper Reports North’s Scud Missile Deployment,” Seoul Sinmun, February 24, 1992, p. 8. ↩

- CSIS’s Korea Chair is currently preparing a report on the Kal-gol missile operating base. ↩

- “North Said to Develop Scud Mobile Launcher,” Yonhap, October 4, 1991. ↩

- Up until recently Kal-gol was also the author’s understanding of location for the 1991 training/test launch of the Hwasong-6. New information, however, suggests that it was conducted by the unit from the Kumchon-ni missile operating base. Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. ↩

- “DPRK Building ‘At Least Five’ Underground Missile Sites,” Yonhap, January 8, 1999; “Pyongyang Found Constructing 5 Underground Facilities,” Yomiuri Shimbun, January 8, 1999; “DPRK Said to Deploy Missiles at More Than 10 Sites,” Yonhap, January 6, 1999; and Fulghum, David A. “North Korean Forces Suffer Mobility Loss,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, November 24, 1997, p. 62. ↩

- Yang-jun Hwang, “North Korea, Constructing 6 Missile Bases for 550km Range Missiles,” Hankook Ilbo, October 27, 1999, http://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/199910270050091983; and “North Korea, 3 Locations Along MDL Deployment Preparation,” Chosun Ilbo, September 29, 1999, http://news.chosun.com/svc/content_view/content_view.html?contid=1999092970058. ↩

- A Primer on the Future Threat, The Decades Ahead: 1999-2020 (Washington, D.C.: Defense Intelligence Agency), July 4, 1999, pp. 79-80. ↩

- There are numerous different naming conventions or transliterations for the villages, towns and cities in the Kumchon-ni area. In general, those used by the NGA are used in this report. Some of the more notable differences are: Singol-li is sometimes identified as Shingonri, Shingonri2-gu, Shingon-li or Shingol on Korean maps; and the Oeryongdae area is identified as Hayong-ri or Hayong on Korean maps. ↩

- “ROK Defense Ministry Claims DPRK Building Missile Power as World Debates US Plan,” JoongAng Ilbo, March 12, 2001, p. 2; “Expansion of North Scud Missile Base,” JoongAng Ilbo, March 5, 2001, https://news.joins.com/article/4045601; Kang Ho-sik, “North’s Missiles Increase. Strategic, Forward Deployment Both in and Out,” Kyunghyang Shinmun, March 5, 2001, https://www.bigkinds.or.kr/news/newsDetailView.do?newsId=01100101.20010305000000301; and Kang Ho-sik, “North Korea Constructs More Scud Missile Bases,” Kyonghyang Sinmun, March 4, 2001, http://www.bigkinds.or.kr/news/newsDetailView.do?newsId=01100101.20010305000000102. ↩

- Yu Yong-won, “Pros and Cons of Sunshine Policy: ROK and United States ‘a World Apart’ on Assessments of North Korean Military Force,” Chugan Choson, April 10, 2001. ↩

- Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.; and Yu Kang-mun, “Activity of North Korea’s Missile Launch Preparations,” Hankyoreh, September 24, 2004, https://news.naver.com/main/read.nhn?mode=LSD&mid=sec&sid1=100&oid=028&aid=0000079504. ↩

- For example: Lee Yong-min, “North Korea Ballistic Missile Politics,” Institute for Democracy, December, 2017, http://www.idp.or.kr/lib/file_down.php?bf_idx=1516; Yu Yong-won, “North Korea’s Ballistic Missile Bases, 13 Locations Among 3 Belts,” Chosun Ilbo, November 14, 2018, http://news.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2018/11/14/2018111400327.html; and Yang Nak-gyu, “North Korea’s Missile Bases Unveiled by Foreign Military Intelligence Company,” Asia Business Daily, February 23, 2019, http://www.bigkinds.or.kr/news/newsDetailView.do?newsId=02100801.20190223060400001. ↩

- It is unclear if any of these developments were related to expanding support for the personnel operating the nearby Hwangnyong-san early warning radar base. ↩

- Additional launches during 2009 and 2014 appear to have been from either the Kittae-ryŏng area or another location in the general area. CSIS’s Korea Chair is currently preparing a report on the on the Kittae-ryŏng ballistic missile training facility. ↩

- Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. ↩

- The greenhouses and agricultural support activities are not unusual within the KPA as all units have a varying level of responsibility for growing their own food. ↩

- It should be noted that preliminary data suggests that KPA ballistic missile organizational structures do not necessarily neatly fit into western organizational structures and that force structures have changed over time. Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.

A 1994 unclassified assessment the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency credits a KPA Scud battalion with 173 personnel and 6 TELs. Defense Intelligence Agency, North Korea Handbook, 1993, p. 5-22. By comparison Cold War-era Soviet Scud/Scaleboard brigades had a personnel strength of approximately 1,200 and 9 TELs. U.S. Army, Opposing Forces: Europe, FM 30-102, 1 June 1973, p. 13-6. ↩

- This AAA position is at the Hwangnyong-san Early Warning Radar Base. ↩