A Case for Rajin Port: Economic Significance and Geopolitical Implications

Updated on May 12, 2021 to include the full report.

Let us imagine that sometime in the future, a significant political shift occurs in North Korea such that sanctions are lifted, and full-scale foreign direct investment projects become feasible. In such an environment, which infrastructure projects might fundamentally shift the regional economic landscape? And how might those projects alter the geopolitical dynamics of Northeast Asia? Among a multitude of potential investment opportunities that we identified, a particularly compelling case emerged for Rajin port.

The reality is, Rajin holds considerable economic value, and its viability stems from its potential to act as a regional logistics hub linking the Chinese northeastern provinces, Far East Russia and North Korea. For China, the development of the northeastern provinces of Heilongjiang and Jilin hinges on access to a seaport. Having long suffered from stagnated growth and brain drain, the region is further weighed down by inefficient transport options that continue to stymie its economic potential. Without access to the sea, goods from Heilongjiang must currently be driven 1,400 kilometers to Dalian, whereas the distance to Rajin is only ~ 600km, offering a potential to save logistics costs by up to 36%.1

Russia, meanwhile, will also look to Rajin as a window of development for the Far East region. In particular, the advent of climate change has increased the feasibility of trade via the Northern Sea Route. Putin, in just 2019, added the Arctic under the jurisdiction of the “Ministry for the Development of Russian Far East and Arctic” in order to address such a development agenda.2 However, since most of Russia’s ice-free ports hold limited depth, they are unable to accommodate the necessary capacity. The development of Rajin, a natural ice-free deep-water port, therefore holds significant investment value for Russia’s Far East. Additionally, the port is readily positioned to absorb economic growth in the industrial hinterlands of North Korea in the areas of manufacturing and processing, as well as logistics. All told, the growth drivers in the surrounding regions signify a sizable investment value for Rajin port.

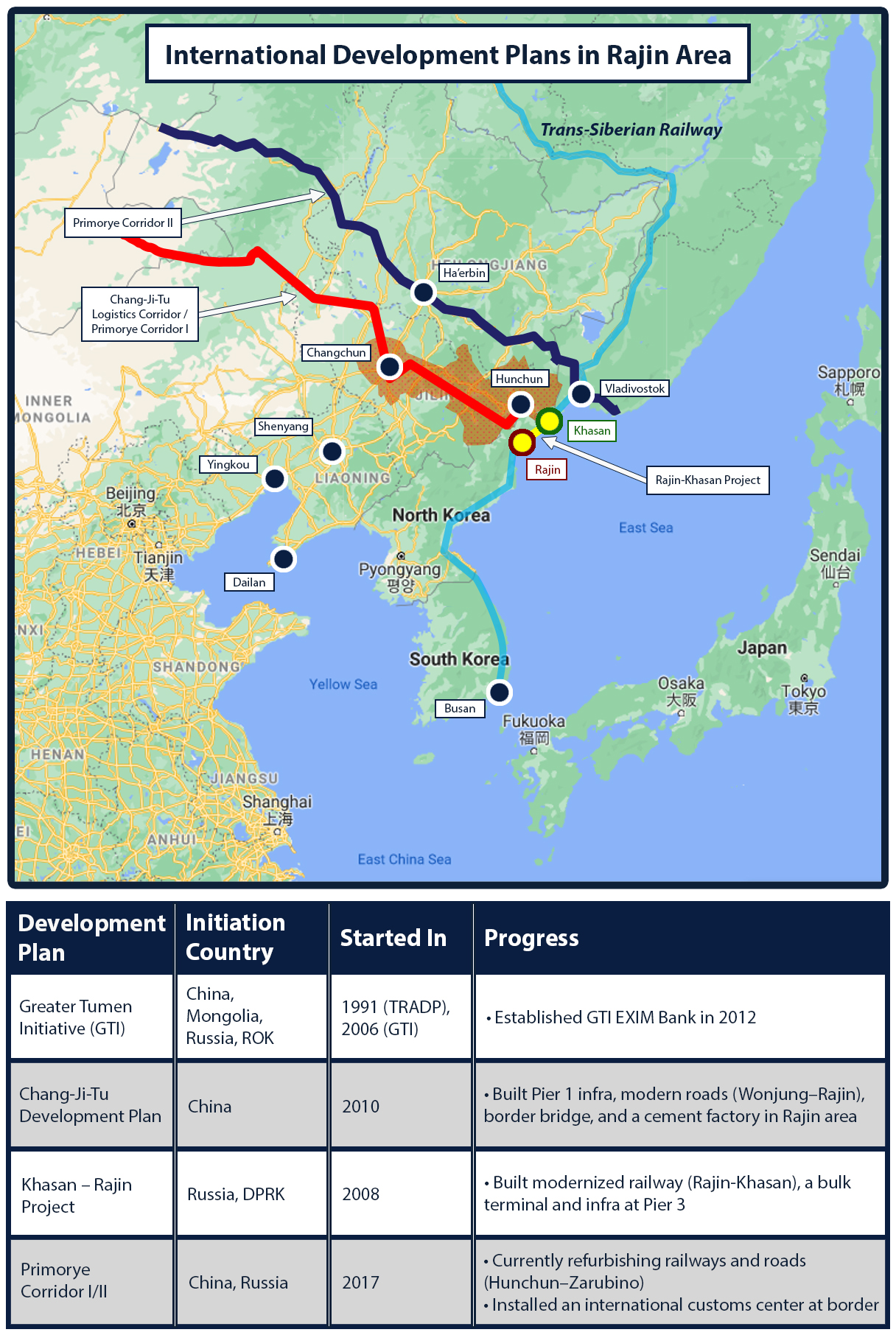

Recognizing such opportunities, regional actors have made numerous attempts over the years to gain influence over Rajin’s development and operational rights. In 1991, the United Nations Development Programme put its support behind the Tumen River Area Development Programme (TRADP, which later became the Greater Tumen Initiative), an attempt to promote regional economic cooperation among China, Russia, North Korea, South Korea, and Mongolia. However, due to a lack of clear project objectives and conflicts of interest among members3, the program failed to attract any major investments, leading to North Korea’s withdrawal in 2009.4 Subsequently, North Korea returned to its tactic of leveraging China and Russia against each other, attempting to solicit infrastructure investments from both.5

In early 2008, North Korea and Russia agreed to launch the Rajin-Khasan Project6, a joint venture between the two for the development and operational rights of Rajin’s Pier 3, as well as the construction of logistics infrastructure7 linking Rajin and Khasan, a Russian border city. The joint venture turned Pier 3 into a bulk terminal, which underscored Rajin’s potential as an export hub for Russian natural resources.8 However, following North Korea’s 2016 nuclear tests and resulting sanctions, the project has been put on hold.

Meanwhile, China sought to link its landlocked provinces to Rajin and Russia’s Zarubino port through its own Chang-Ji-Tu development initiative. In 2011, China and North Korea agreed on a comprehensive plan for the joint development and management of the Rason area9, which led to investments in Pier 1 and the construction of a border bridge to Rajin.10 No further development took place, however, due to the 2013 purge of Kim Jong-un’s uncle, Jang Song-thaek, who had been leading the project.

After hitting a proverbial political wall, China and Russia, at the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) forum in 2017, signed an agreement to develop the Primorye International Transport Corridors11 aiming to shift the shipping demand of inland cities to Russian ports. Thus far, however, the shipping volume through the Primorye Corridor has been negligible.12 Part of this is a practical limitation, as the ports are already running at full capacity. However, the Russians are also conscientiously avoiding the Far East’s economic dependence upon China,13 thereby constituting a political limit to the region’s development potential.

While the economic implications of Rajin’s development are clearly immense, the de-sanctioned use of the port poses considerable political and security questions as well. If China or Russia gains a significant stake in Rajin, their financial leverage could be used to assert dual use rights. For example, as witnessed in Djibouti, Sri Lanka, or Pakistan – China’s “string of pearls” ports in the Indian Sea – Rajin may serve as a strategic point from which to exert military dominance over the region. Such a move in the East Sea could pose security challenges for South Korea and Japan, while also limiting US military options in the Pacific.

Depoliticizing Rajin port will require simultaneously building logistical capabilities while also preventing operational intervention by any one individual country. In such case, a multilateral bank would be a good candidate to initiate Rajin’s infrastructure development. Institutions such as the World Bank or Asian Development Bank, are “less vulnerable to risks of moral hazard and politicization” (Haggard and Noland, 2017) and could provide a financing and governance structure for the region in a denuclearization scenario.14 They can also offer critical oversight, safeguards, and resources for capacity building, to ensure the port is developed in a sustainable manner.

Although the political conditions surrounding North Korea’s economic future are impossible to predict, the persistent jockeying for access to Rajin suggests that it could become a harbinger of the region’s economic success. As a trilateral logistics hub, Rajin could invigorate the lagging economies of northeastern China, North Korea and Far East Russia. However, the immense transformative change required in North Korea for such investments to take place could also inflame existing tensions among neighboring states. Multilateral banks, by design, offer the best chance for peaceful mitigation in this context; with the ability to both address Rajin’s development value while also preserving geopolitical stability. As the port’s development poses such consequential implications, the international community should devise blueprints for Rajin’s future.

References

- 이 성우. “북방 물류시장과 나진항 연계 가능성 검토.” KMI 한국해양수산개발원-현안연구. Korea Maritime Institute, April 24, 2015. http://www.kmi.re.kr/web/board/download.do?rbsIdx=287. ↩

- 조 영관. “북중러 교통물류 협력과 신북방정책에 대한 시사점.” Issue Report 2019, no. 지역이슈-2 (October 2019). https://eiec.kdi.re.kr/policy/domesticView.do?ac=0000151048&issus=. ↩

- 김 천규. “The Strategic Suggestions on Cross-Border Cooperation Projects in the Tumen Region.” 국가정책연구 포털. KRIHS. 2019. https://www.nkis.re.kr:4445/researchReport_view.do?otpId=KRIHS00031328#none. ↩

- 조 명철, and 김 지연. “GTI(Greater Tumen Initiative)의 추진동향과 국제협력 방안.” KIEP, December 30, 2010. http://www.kiep.go.kr/sub/view.do?bbsId=search_report. ↩

- 김 천규, 2019 ↩

- The project established a joint venture, 70% owned by Russia and 30% North Korea. In 2013, Russia sought to sell 49% of its stake to ROK, turning the project into a Russia-ROK-DPRK JV. (김 천규, 2019) ↩

- The project modernized a 54km railway between Rajin and Khasan, enabling trains from both countries to directly access both cities. (김 천규, 2019) ↩

- Russia exported 4.8 million tonnes of coal to China through Rajin from 2013 to 2017 (조 영관, 2019) ↩

- “North Korea – China Agreement on Joint Development of Rason Special Economic Zone and Golden Triangle Bank Economic Zone (2011-2020)” ↩

- Hunchun Chuangli Shipping and Logistics Ltd., a state-owned enterprise of Hunchun City, acquired the operation rights via renovating Rajin’s Pier 1 in 2009. (김 천규, 2019.) ↩

- Russia and China Sign Agreement on Development of Primorye 1 and Primorye 2 International Transport Corridors.” PortNews, July 5, 2017. https://en.portnews.ru/news/241731/. ↩

- Interview with an official at Korean Ministry of Unification ↩

- While the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689) established the border in favor of the Chinese, the later Treaty of Peking (1860), signed after China’s weakened position from the Opium Wars, effectively blocked China from direct access to the East Sea.This so-called Amur Annexation remains as a centuries old political sensitivity between China and Russia. ↩

- Haggard, Stephen and Marcus Noland. Hard Target: Sanctions, Inducements, and the Case of North Korea. n.p.: Stanford University Press, 2017. ↩