What is the Significance of North Korea’s Rail-mobile Ballistic Missile Launcher?

This article was originally published as a CSIS Korea Chair Platform.

Key Points

- North Korea’s demonstration of a rail-mobile ballistic missile launch platform, along with solid propellant SRBMs, if more fully adopted, will increase the survivability of their ballistic missile force from successful pre-emptive first strikes.

- North Korea’s interest in rail-mobile ballistic missile launch platforms likely dates to the late-1980s or early-1990s but accelerated in the 2000s as international sanctions reduced the availability of TELs and MELs.

- The North is heavily mountainous and possesses a widely distributed rail network with hundreds of tunnels and rail-accessible remote facilities that can provide excellent locations to conceal and support operations of rail-mobile ballistic missiles.

While the timing of North Korea’s public demonstration of a KN-23 short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) rail-mobile missile launch platform on September 15, 2021 may have come as a surprise to defense and intelligence officials, the fact that they have been interested in developing such a capability was not. The subject of North Korean development of rail-mobile missile launch platforms has been of interest for years because of its potential to complicate planning and wartime targeting, with media reporting of such interest dating back to at least August 2016. This Korea Platform provides a brief description of its development, technical characteristics, and potential operational procedures.

Development

Interview data suggests that the development of a rail-mobile ballistic missile launch platform, along with other basing options, was likely considered by North Korean strategists and planners since the early stages of the nation’s ballistic missile program. However, with North Korea’s early acquisition of road-mobile ballistic missile transporter-erector-launchers (TEL) and mobile-erector-launchers (MEL) from foreign and domestic sources—and the initially small number of ballistic missiles in its inventory—it appears that the design and development of rail-mobile platforms were relegated a low priority and did not advance significantly during the 1980s – 1990s. However, in the 2000s, the introduction of foreign sanctions led to the precipitous decline in the availability of foreign TELs, MELs, and the components to manufacture them domestically. At the same time, the numbers and types of ballistic missiles in inventory were steadily increasing. Interview data suggests this resulted in a policy decision issued by the Second Economic Committee to secure additional and alternate launch platforms, including rail-mobile, becoming an increasingly high priority. This increased priority was accompanied by the introduction of solid-fueled missiles such as the KN-02 SRBM and the subsequent development of the KN-23 SRBM. What appears to be an initial focus on solid fuel systems simplified the task of designing a rail-mobile launcher and supporting railcars over designing them for liquid-fueled ballistic missile systems. However, while it is presumed to have taken place, almost nothing is known concerning the North’s research, development, or production of rail-mobile missile launchers for its larger longer-range liquid fuel ballistic missiles.

The development of rail-mobile launch platforms offers significant benefits from the North Korean perspective. Among these are:

- Rail-mobile missile platforms can easily move randomly on the rail network, which complicates targeting and increases survivability. It provides operational and strategic opportunities to complicate South Korean and U.S. planning and wartime targeting of the North’s increasingly vulnerable ballistic missile operating bases and support infrastructure.

- The type of rail-mobile missile launch platforms that North Korea is assessed to be developing are relatively inexpensive and easy to design and manufacture.

- The costs in manpower and other resources to operate solid-fuel rail-mobile missile launch platforms are significantly lower than for comparable liquid-fuel systems.

- The North is heavily mountainous and possesses a widely distributed rail network with hundreds of tunnels and rail-accessible remote facilities that can provide excellent locations to conceal and support operations of rail-mobile ballistic missiles. In 2014, North Korea’s rail network was known to be consisted of 7,435 kilometers of rail lines of which 5,400 kilometers were electrified. By comparison, in 2016 South Korea was known to have a rail network consisting of 3,979 kilometers of which 2,727 kilometers were electrified.

A perfect example of this last benefit is exemplified by the September 15, 2021 test launch. This test took place in Yangdok-kun (Yangdok County) on a section of the Pyongra Rail Line that connects Pyongyang to Wonsan and points north. Within five kilometers east or west of the reported launch position, there are nine railroad tunnels on the same rail line, including one that is approximately 1.3-kilometers-long and another that is approximately 1.5-kilometers-long.

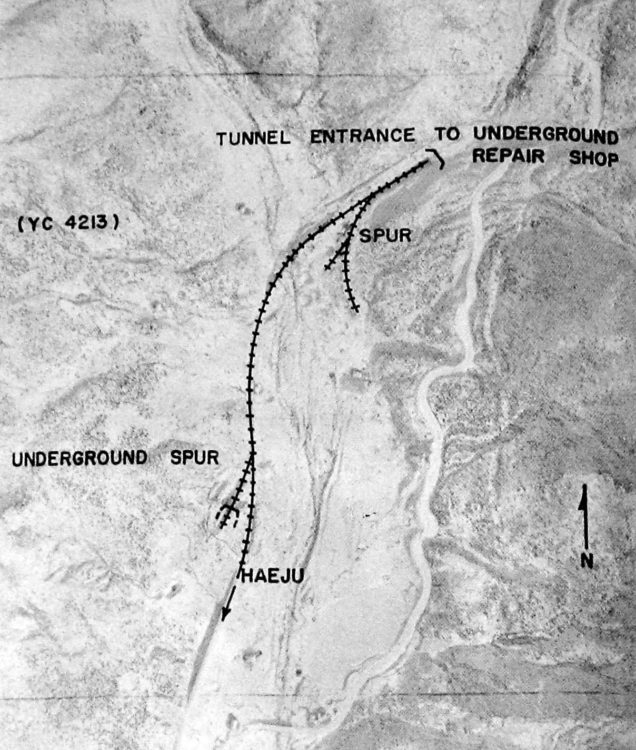

The above characteristics are enhanced by North Korea’s little-understood history of using railroad tunnels for military purposes that dates to the Korean War and is regularly studied at the Pyongyang Railway College. During the war, UN Command’s air superiority destroyed or neutralized a vast majority of the North’s manufacturing and transportation infrastructures. Despite concerted and prolonged efforts by UN Command air forces, they were never able to destroy or neutralize the North’s rail network for any significant length of time. This network became the primary means of moving equipment and war supplies around the nation, and the railroad tunnels regularly served as shelters for rail equipment and supplies, and for repairing military equipment.

Following the war and through at least the late 1990s, North Korean railroad tunnel construction has often included internal rail sidings or rail spur lines leading to large shelters or military facilities. There are also dedicated military rail spur lines in mountainous regions that terminate in underground facilities. While recent information concerning railroad tunnel activities is limited, such activities have been noted by escapees and defectors.

Railcars

The video of the KN-23 “railway-borne missile regiment” conducting the test launch shows that it consisted of one diesel locomotive and two railcars—one for the operating crew and one with the missile launcher itself.

- Both railcars are based upon a standard cushioned two-truck (the wheels the car rides on), two-axle, steel boxcar design with double sliding doors on each side. White reporting marks are noted on both railcars.

- The two-truck, two-axle design, not unexpectedly, indicates that neither railcar is extremely heavy and that both are theoretically capable of riding some of the lighter rail lines present in more remote areas and industrial spur lines. This latter point should be taken carefully since the September 15 test was conducted on a section of rail with concrete railroad ties (sometimes called “sleepers”)—the wood or concreted parts laid under and between the rails to support and hold them in position. Such concrete ties provide greater stability and load-bearing capability than the wooden ties impregnated with creosote found throughout North Korea’s rail network. This section of rail was by North Korean standards also well ballasted (ballast are the rocks under and to both sides of the tracks and ties that hold them tightly in position). This may suggest that the North was either taking all steps to ensure the test’s success or that missile launches may require the extra support provided by rail sections supported by well ballasted concrete railroad ties.

- The crew railcar shows no significant external modifications of significance. From what little can be seen inside the car, it appears that there were also no significant internal modifications and that it was relatively empty.

- The missile launch car appears to be a standard boxcar design that has been heavily modified. Among these modifications are:

- Installation of two full-length folding roof doors. While the large seam where the full-length folding roof doors join would appear to be a distinctive identification characteristic for rail-mobile launch systems, this should not be taken for granted as a seam such as this can readily be manufactured and applied to non-launch railcars or be confused by roof walkways on older boxcars.

- Installation of a steel wall down the center of the car to support the folding roof doors.

- Reinforced sidewalls to accommodate the folding roof doors and their opening mechanisms.

- Replacement of the standard double sliding doors on each side with wider doors.

- The addition of two smaller doors on both sides of the car at the front and rear ends. From the video of the test, these are for exhaust and overpressure release purposes.

- Installation of an exhaust deflector inside the smaller front and rear doors to expel the hot exhaust out both sides of the railcar. This deflector looks like a modified version of an SA-2 (S-75 Dvina) surface-to-air missile exhaust deflector.

- Installation of two single KN-23 launchers inside the railcar. These are separated longitudinally by the center support wall, with the base of each launcher positioned close to the trucks at either end of the railcar. This positioning allows for the weight of the launchers and missiles to be distributed closer to the strongest part of the railcar and balances the weight evenly from front to rear.

From what is currently known and confirmed regarding the current state of railcar manufacturing in North Korea, if these cars were not manufactured in a specialized facility, the Wonsan Railway Rolling Stock Complex in Kangwon-do (Kangwon Province) is the most likely factory for their construction/modification.

An unconfirmed August 2016 Radio Free Asia report appears to support this assessment by identifying production of a “mobile, long-range missile launch vehicle that uses the railway [at the] 6.4 Vehicle Factory.” According to the report, as well as author’s interview data, the 6.4 Vehicle Factory (more commonly the June 4 Factory) is the previous name for the current Wonsan Railway Rolling Stock Complex.

This same report goes on to extensively describe both a different class of rail-mobile missile launcher (8-axle) than the one observed (4-axle) during the September 15 test launch, and a rail-mobile missile launcher potentially capable of transporting and launching intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM):

“I did not directly observe the freight/cargo vehicle with the missile launch platform installed, but I know it is a 14-axle vehicle that is more robust than the existing 8-axle. …it is known that the long-range missile and launch platform to be mounted on the freight vehicle weighs over 100 tons. …The weight of the mobile missile launcher is a problem.”

This description is of a larger (14-axle) and heavier (over 100 tons) class of railcar than is known to have been manufactured by the Wonsan Railway Rolling Stock Complex, other railcar manufacturing plants, or observed on North Korea’s rail network. While the North has undoubtedly explored the potential for a rail-mobile missile launcher for its larger liquid fuel ballistic missile, nothing of reliable substance is known of such efforts. Until reliable information develops, this description should be viewed with utmost caution.

Unit Organization

North Korean media has described the test as being conducted by a new “railway-borne missile regiment [that was] created at the Eighth Party Congress in January [2021] and that there are plans to…expand the regiment into a brigade.” If this unit is an operational unit—rather than a research, testing, development, and evaluation (RTD&E) unit—what the world saw was only a portion of the regiment.

Given what little is known concerning the organization of North Korean ballistic missile units, a full rail-mobile missile regiment would likely consist, at a minimum, of a headquarters unit and two launch batteries/sections. The headquarters unit would include the regimental support units, including technical, survey, fire control, missile reload (with cranes and transloading vehicles), etc. A full launch battery/section, excluding locomotive, would likely consist of 2-5 railcars depending upon the presence of a second missile launch car. It is likely that the diesel locomotive seen in the released video was operated by the Ministry of Railroads and temporarily assigned to the “regiment” for the test launch. While exact identification of the locomotive seen in the released video is challenging, it appears to be a M65 originally manufactured by the former Soviet Union and acquired secondhand from East European countries. Additionally, it is unclear whether diesel locomotives will be permanently assigned to future railway-borne missile regiments or brigades, or be a pooled resource.

Operational Procedures

Several characteristics reported or observed during the test indicate that the “railway-borne missile regiment” followed known or frequently observed ballistic missile unit operational procedures:

- Movement to a pre-surveyed launch site 6 to12 hours before launch. North Korean media stated that the “railway-borne missile regiment” was moved from its operating base “to the central mountainous area at dawn on September 15″—the day of the test launch.”

- Satellite imagery and the released video indicate that the movement to the launch site and the test launch took place on an overcast day. Operating under cloud cover to mitigate overhead observation has become a common operating procedure for ballistic missile units conducting tests and more general unit movements.

- While ballistic missile units appear to conduct operational readiness tests on a rotating 2- to 4-year training cycle, this test was conducted as a “without notice” test to validate “the combat preparedness of the new regiment [and the] practicability of the railway mobile missile system deployed for the first time for action.” This description appears to be somewhat more the function of an RTD&E unit rather than an operational unit.

- The use of a diesel locomotive during the September 15 test may reflect an understanding that during wartime, its fleet of electric locomotives will likely become unavailable as power stations and distribution nodes are quickly destroyed.

While it is too early to imply any comprehensive understanding of North Korean strategic thought from this recent test, the media statement that the “railway mobile missile system is an effective counter striking means to deal a heavy blow at the threatening forces with dispersive firing across the country” is intriguing. It suggests that the North may view the rail-mobile KN-23 SRBM launchers as a counter strike or retaliatory force rather than a preemptive or first strike force within the context of its evolving nuclear and ballistic missile doctrines and strategies.

Analytical Cautions

While the above analysis provides some preliminary background on North Korea’s development of rail-mobile missile launch platforms, technical characteristics, and observed operational analysis of the recent rail-mobile KN-23 test launch, several notes of caution are required:

- It is unclear if what was demonstrated at the recent launch was an operational rail-mobile missile launch platform or a testbed/prototype.

- North Korea has an extremely long history of duplicity and showing the world only what it wants to show as a means of manipulating media opinion and analysis and painting a picture of a strong and prosperous nation. This includes the public display of dummy systems, mockups, or testbeds/prototypes of weapons systems that were never further developed.

- The North has an equally long history of waiting years to display new weapon systems or not publicly displaying certain weapons at all (e.g., there are TELs, MELs, and missile support vehicles that have never been seen publicly). The KN-23 rail-mobile launcher may be an example of this “delayed” practice, as an unconfirmed 2016 report states that “North Korean engineers have been working on the mobile missile system since May [2016 and that] …technicians have built some six railway-mounted launcher vehicles per month.”

- Despite North Korean statements, there are no practical means of assessing the size or viability of any North Korean rail-mobile missile force.

- Analysts and pundits need to be extremely careful in assigning capabilities to North Korea’s ballistic missile force that may not be there.