Yongbyon’s Status during the Trump-Kim Summits: A Thermal Analysis

Key Findings

- Despite the goal of advancing denuclearization of the Korean peninsula through leader-to-leader exchanges in 2018 and 2019, thermal infrared (TIR) imagery of the Yongbyon Nuclear Research Center around the summit dates reveals limited impact on Yongbyon’s overall operational status.

- Prior to the first summit meeting between Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un at the Singapore Summit on June 12, 2018, key facilities such as the 5MWe reactor and centrifuge plant remained operational, indicating minimal or no impact of the scheduled diplomatic event on the operations at Yongbyon.

- However, in the period between the conclusion of the Singapore Summit and the start of the Hanoi Summit on February 27-28, 2019, there was a hiatus in operations of the 5MWe reactor and experimental light water reactor (ELWR) (plutonium-producing facilities), as well as the Radiochemistry Laboratory (reprocessing facility), possibly reflecting the summit’s impact on nuclear operations.

- During the same period, other sources such as the IAEA suggest that the centrifuge plant (highly enriched uranium-producing facility) remained operational, underscoring North Korea’s true long-term nuclear ambitions and indicating the stoppage at Yongbyon was temporary and related only to plutonium production.

- After the failure of the Hanoi summit in February 2019, increasingly concentrated thermal patterns were detected which suggests a restart of all operations at Yongbyon.

- This correlation suggests that any future summitry or return to negotiations could temporarily halt some fissile production and reprocessing operations at Yongbyon conditionally, but that any long-lasting freeze would require a negotiated agreement in which DPRK would receive compensation for an operational halt to Yongbyon.

Building on Beyond Parallel’s previous analyses, this report provides analysis of thermal infrared (TIR) imagery of the Yongbyon Nuclear Research Center around the 2018 Singapore Summit and the 2019 Hanoi Summit between President Donald J. Trump and General Secretary of the Workers’ Party of Korea Kim Jong-un to determine what, if any, effects the summits had upon operations at the center’s key fissile material production facilities. While TIR analysis alone cannot provide conclusive evidence of a facility’s operational status, when supported by open source information, the findings indicate that key fissile material production facilities were likely operational before the 2018 Singapore Summit. However, in the period between the conclusion of the Singapore Summit and the start of the 2019 Hanoi Summit, some facilities halted operations. After the failure of the Hanoi summit in February 2019, increasingly concentrated thermal patterns were detected which suggests a restart of all operations at Yongbyon. This correlation suggests that any future summitry or return to negotiations could temporarily halt some fissile production and reprocessing operations at Yongbyon conditionally, but that any long-lasting freeze would require a negotiated agreement in which DPRK would receive compensation for an operational halt to Yongbyon.

Methodology

Similar to our previous TIR analysis series, Beyond Parallel used medium-resolution (~100m) thermal imagery available from LANDSAT-8, which has a revisit rate of 16 days.1 The collected LANSAT imagery was converted to land surface temperatures (LST) using techniques widely described in published remote sensing journals and routines available in many desktop software programs. The resulting temperatures were then normalized to compare to each other and determine thermal patterns and changes. The thermal analysis was then layered on top of high-resolution multispectral imagery from Airbus.

Normalizing LST values allows for comparison across different months and seasons by adjusting for the natural temperature variations that occur due to changes in atmospheric conditions, surface properties, and solar radiation throughout the year and seasons. This normalization process involves scaling the LST data to be directly compared across different periods, effectively removing the influence of seasonality.

It is important to address the limitations of TIR analysis. The resolution of a LANDSAT image, at medium resolution, is not comparable to high-resolution multispectral images. Additionally, although TIR analysis can indicate that certain facilities were emitting higher than average temperatures, it cannot determine what specific processes are underway. For example, it cannot differentiate between a reactor undergoing maintenance and one producing plutonium for weapons. There’s also the challenge of potential countermeasures being employed by the observed facilities, such as thermal camouflage or operational adjustments to minimize thermal emissions remotely detectable. For more on the limitations of TIR analysis, please see our previous report.

Another serious constraint on the analysis is the availability of cloud-free imagery. For reviewing changes in operations before and after the summit, a period of seven months around each summit date was used (three months before, month of, and three months after the summits). LANDSAT images from March to September were reviewed for the Singapore Summit, which occurred on June 12, 2018. However, there were no cloud-free LANDSAT images suitable for accurate TIR analysis in May, July, August, and September. For the Hanoi Summit, which occurred from February 27 to 28, 2019, images from November 2018 to May 2019 were reviewed. Out of these images, November and March had no cloud-free images suitable for TIR analysis.

Finally, the last caveat to consider is that open source information was also used to supplement this analysis. While we relied on established sources of information, there may be instances when such information is inaccurate or not detailed enough to identify day-to-day operations. For example, when a reactor is described as having had an interruption in the middle of the month, it is challenging to determine whether a TIR image taken on the 13th of the month falls within this period of interruption.

2018 Singapore Summit

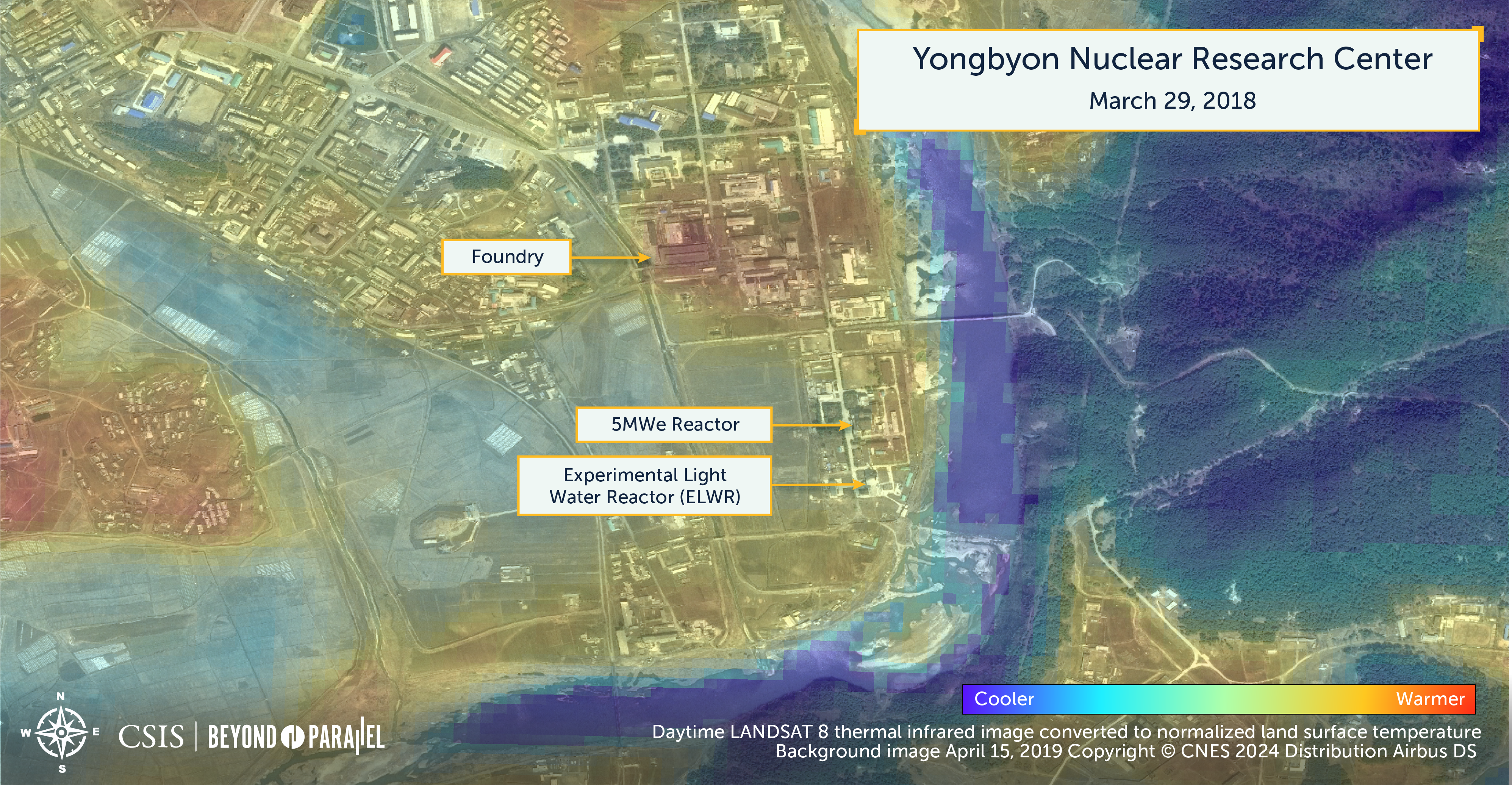

Overviews of the normalized land surface temperature calculated from daytime LANDSAT 8 thermal infrared (TIR) image taken in months leading up to the Singapore summit. (Base Image Copyright © CNES 2024 Distribution Airbus DS) Image may not be republished without permission. Please contact imagery@csis.org.

The “first, historic summit” between President Trump and Kim Jong-un, which took place in Singapore on June 12, 2018, produced a list of commitments for both parties, including the commitment by North Korea “to work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.”2 However, during the lead-up to the summit, open source information indicates that some of Yongbyon’s key facilities—namely the 5MWe reactor and the centrifuge plant—were operational. The 5MWe reactor was assessed to have been in operation throughout the period. Although “operations were suspended for a few days in February, March and April 2018, each period was insufficient to shut down for discharge and was likely for maintenance operations.”3 Additionally, the IAEA reported the centrifuge plant in the southern section of the center as having “indications consistent with the use of the reported centrifuge enrichment facility.”4

Conversely, the other two key facilities at Yongbyon—the experimental light water reactor (ELWR) and the Radiochemistry Laboratory—were likely not fully operational in the months leading up to the summit according to open source information. The ELWR was likely not operational in the months leading up to the summit as construction of a new building was ongoing during this time inside the security perimeters of the reactor.5 At the Radiochemistry Laboratory and the associated steam plant, the United Nations Panel of Experts (UN PoE) reported “possible operations,” pointing to the “Plumes of smoke and fluctuating amounts of coal reserves were seen between 27 April and 8 May 2018… which was likely for maintenance work.”6 However, the IAEA assessed that the observed activity at the steam plant “was not sufficient to have supported the reprocessing of a complete core from the 5MW(e) reactor.”7

Between March and September 2018—three months before and after the summit in June—only March, April, and June have cloud-free LANDSAT images suitable for accurate TIR analysis. These images show that:

- At the 5MWe reactor, which was known to have been operating during the study period, no strong thermal patterns were observed in March and April, whereas a stronger but still not indicative thermal pattern was observed on June 1, 2018, just eleven days before the Singapore summit.

- At the ELWR, which was assessed to not have been operational during the study period, no strong thermal patterns were observed in any of the images.

Closeups of the normalized land surface temperature calculated from daytime LANDSAT 8 thermal infrared (TIR) image taken in months leading up to the Singapore summit. (Base Image Copyright © CNES 2024 Distribution Airbus DS) Image may not be republished without permission. Please contact imagery@csis.org.

- At the Radiochemistry Laboratory and its associated thermal plant, which was known to have had maintenance work but was not fully operational, no strong thermal patterns were observed in March and April. While a stronger thermal pattern was observed on June 1, this is likely due to the valley’s heat-trapping topography and the heat-absorbing properties of the lab’s roofing. These factors can mask or exaggerate the thermal signatures of operational status.8

- At the centrifuge plant, which was reported by sources such as the IAEA to have been operational during the study period, none of the studied images show strong thermal patterns that support its operational status. The lack of thermal signature during a known operational period is not usual and is likely due to the nature of operations at the facility, which does not always emit strong thermal signatures. For more on the limitations of TIR analysis, see our previous report.

Closeups of the normalized land surface temperature calculated from daytime LANDSAT 8 thermal infrared (TIR) image taken in months leading up to the Singapore summit. (Base Image Copyright © CNES 2024 Distribution Airbus DS) Image may not be republished without permission. Please contact imagery@csis.org.

The thermal imagery analysis surrounding the 2018 Singapore Summit, along with open source information, shows that key facilities discussed above at Yongbyon likely did not halt operations in anticipation of the upcoming summit. In fact, the strongest thermal patterns observed in early June, just eleven days before the summit, indicate that the summit likely had no or very little impact on the operational status of these locations.

2019 Hanoi Summit

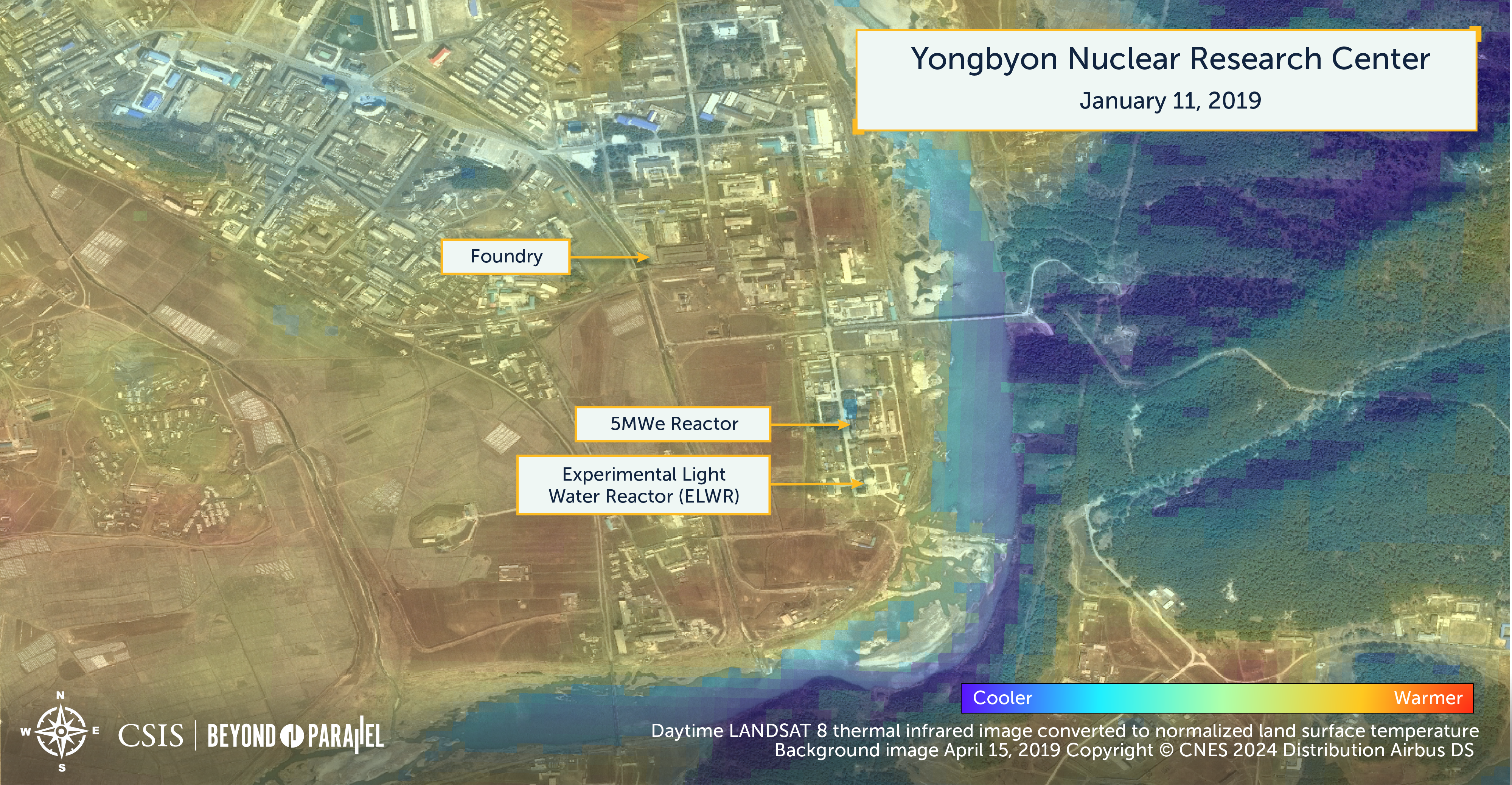

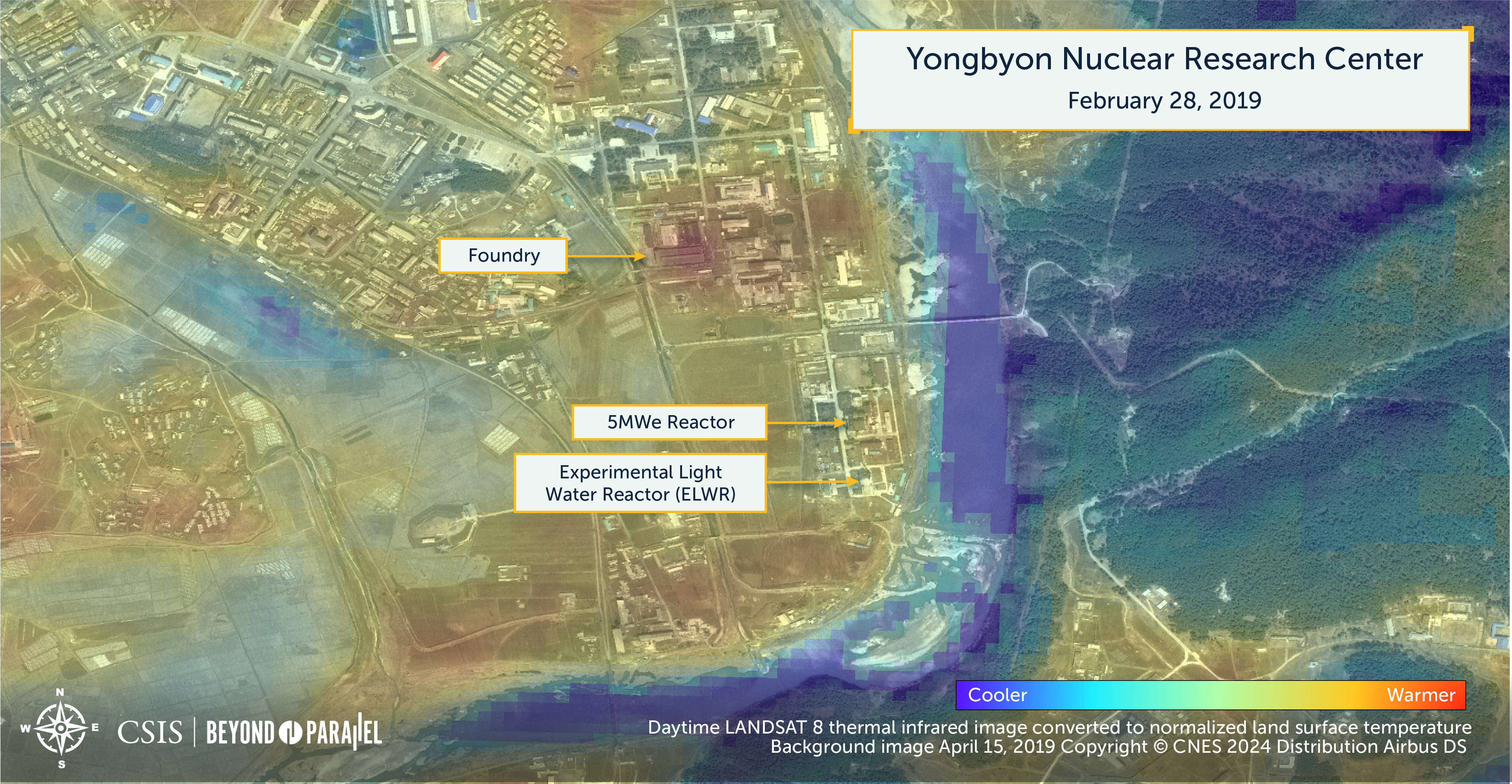

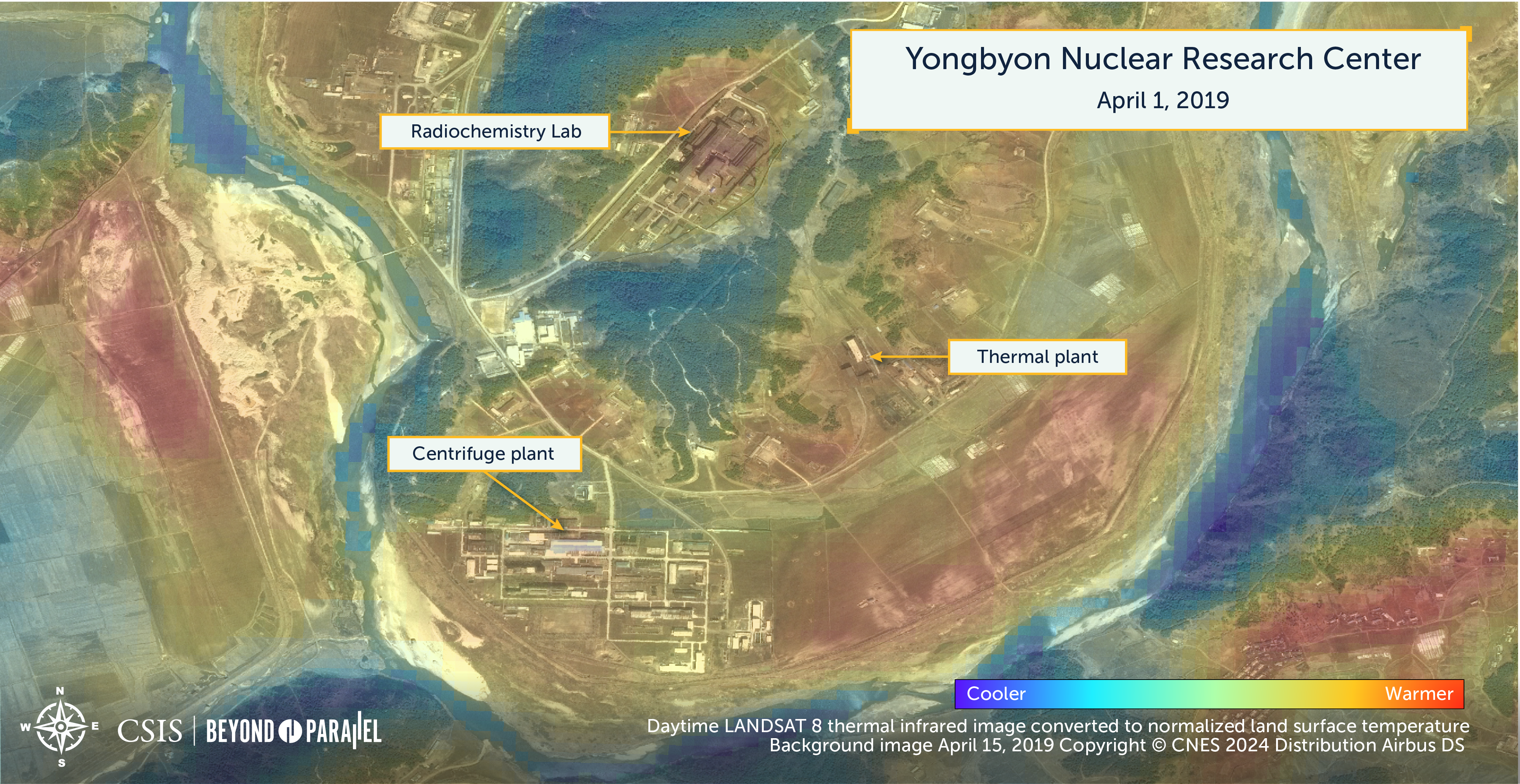

Overviews of the normalized land surface temperature calculated from daytime LANDSAT 8 thermal infrared (TIR) image taken in months leading up to and after the Hanoi summit in February 2019. (Base Image Copyright © CNES 2024 Distribution Airbus DS) Image may not be republished without permission. Please contact imagery@csis.org.

A few months after their first summit, President Trump and Kim Jong-un reconvened in Hanoi on February 27, 2019. The summit continued into the next day before being cut short after North Korea offered the dismantlement of the Yongbyon Nuclear Research Center in exchange for lifting all U.S. sanctions, a “bridge too far” for the U.S.9

Notably, between the June 2018 Singapore Summit and at least three months after the February 2019 Hanoi Summit, the three other key facilities—the 5MWe reactor, ELWR, and the Radiochemistry Lab—were assessed by the UN PoE, the IAEA, and analysts as having halted operations. According to the IAEA,

“from mid-August through late November 2018, there were indications that the [5MWe] reactor was not in continuous operation. Since early December 2018, there have been no indications of the reactor’s operation. The Agency’s observations indicate that the reactor has been shut down for a sufficient length of time for it to have been de-fuelled and subsequently re-fuelled.”10

Satellite imagery leading up to the summit suggested that the ELWR was not operational as water channels for cooling water were partially frozen, among other indications.11 The Radiochemistry Laboratory and the associated thermal plant did not show any indications of reprocessing activity during the studied period barring a heat change detected in November 2018.12 The halt in operations at these three key sites in the months following the 2018 Singapore Summit likely resulted from the commitments toward denuclearization made by North Korea and the United States during the summit.

However, the centrifuge plant at Yongbyon was assessed by the IAEA and South Korea’s National Intelligence Service (NIS) as having been consistently active during the period leading up to the Hanoi summit, underscoring North Korea’s true long-term nuclear ambitions and indicating the stoppage at Yongbyon was temporary and related only to plutonium production.13

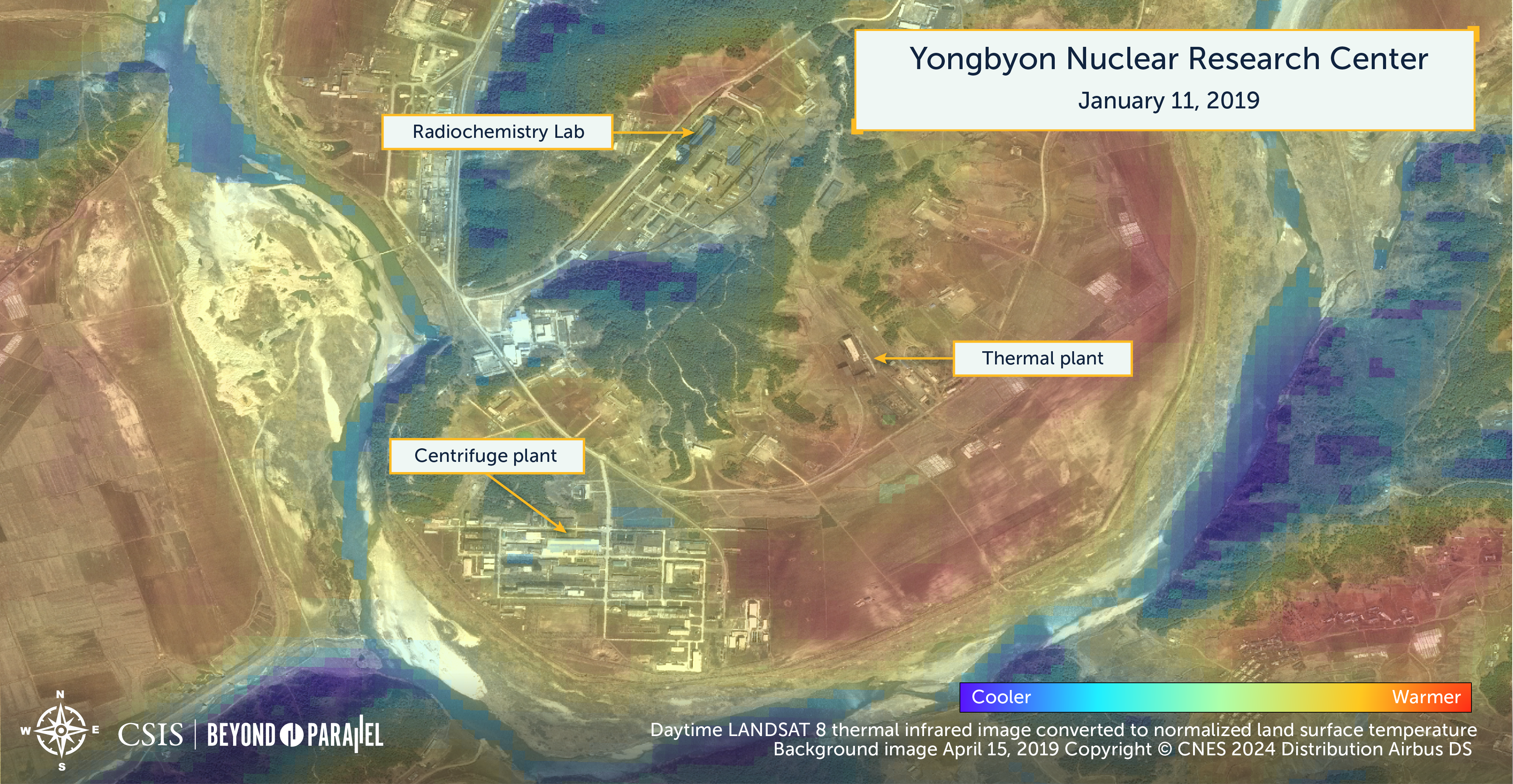

Between November 2018 and May 2019—three months before and after the summit in February—only December, January, February, April, and May have cloud-free LANDSAT images suitable for accurate TIR analysis. These images show that:

- At the 5MWe reactor and the ELWR, which were known to not have been operating during the study period, no strong and concentrated thermal patterns were observed.

Closeups of the normalized land surface temperature calculated from daytime LANDSAT 8 thermal infrared (TIR) image taken in months leading up to and after the Hanoi summit in February 2019. (Base Image Copyright © CNES 2024 Distribution Airbus DS) Image may not be republished without permission. Please contact imagery@csis.org.

- At the Radiochemistry Laboratory and its associated thermal plant, which was not operational, no strong thermal patterns were observed in December and January. However, in February, April, and May—after the Hanoi Summit failed—increasingly concentrated thermal patterns were detected. This thermal pattern was likely due to an increase in activity at the lab, the valley’s heat-trapping topography, the heat-absorbing properties of the lab’s roofing, or a combination of these factors.

- At the centrifuge plant, which was known to have been consistently operational, no strong and significant enough thermal patterns were observed in any of the studied months.

Closeups of the normalized land surface temperature calculated from daytime LANDSAT 8 thermal infrared (TIR) image taken in months leading up to and after the Hanoi summit in February 2019. (Base Image Copyright © CNES 2024 Distribution Airbus DS) Image may not be republished without permission. Please contact imagery@csis.org.

The thermal imagery analysis of images taken a few months before and after the 2019 Hanoi Summit, combined with open-source information, suggests that North Korea had halted operations at key facilities such as the 5MWe reactor, ELWR, and Radiochemistry Laboratory following the 2018 Singapore Summit. However, the centrifuge plant continued its operations, indicating a limited impact of the summits on the operational status of Yongbyon’s key facilities.

Conclusion

The thermal imagery analysis of Yongbyon Nuclear Research Center around the 2018 Singapore and 2019 Hanoi Summits reveals a limited impact of the summits on the overall operational status. Prior to the Singapore Summit, key facilities such as the 5MWe reactor and centrifuge plant remained operational, indicating minimal or no impact of the scheduled diplomatic event on the operations at Yongbyon. However, in the period between the conclusion of the Singapore Summit and the start of the Hanoi Summit on February 27-28, 2019, there was a hiatus in operations of the 5MWe reactor and experimental light water reactor (ELWR) (plutonium-producing facilities), as well as the Radiochemistry Laboratory (reprocessing facility), possibly reflecting the summit’s impact on nuclear operations. During the same period, other sources such as the IAEA suggest that the centrifuge plant (highly enriched uranium-producing facility) remained operational, underscoring North Korea’s true long-term nuclear ambitions and indicating the stoppage at Yongbyon was temporary and related only to plutonium production. After the failed Hanoi summit, thermal analysis suggests that operations were resumed at the previously halted facilities.

Any future summitry or return to negotiations could temporarily halt some fissile production and reprocessing operations at Yongbyon conditionally, but any long-lasting freeze would require a negotiated agreement in which DPRK would receive compensation for an operational halt to Yongbyon.

References

- “Landsat Acquisition Tool,” USGS, https://landsat.usgs.gov/landsat_acq. ↩

- “Joint Statement of President Donald J. Trump of the United States of America and Chairman Kim Jong Un of the Democratic People’s of Korea at the Singapore Summit,” The White House, June 12, 2018, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/joint-statement-president-donald-j-trump-united-states-america-chairman-kim-jong-un-democratic-peoples-republic-korea-singapore-summit/. ↩

- United Nations Security Council, “Report of the Panel of Experts Established Pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009),” S/2019/171, March 5, 2019, 65, https://www.undocs.org/S/2019/171. ↩

- International Atomic Energy Agency. “IAEA Annual Report 2018,” GC(63)/5, August 2018, 19, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/publications/reports/2018/gc63-5.pdf. ↩

- Frank Pabian, Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., and Jack Liu, “New Building Construction Near North Korea’s Experimental Light Water Reactor,” 38 North, March 30, 2018, https://www.38north.org/2018/03/yongbyon033018/. ↩

- United Nations Security Council, “Report of the Panel of Experts Established Pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009),” S/2019/171, March 5, 2019, 65, https://www.undocs.org/S/2019/171. ↩

- International Atomic Energy Agency. “IAEA Annual Report 2018,” GC(63)/5, August 2018, 19, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/publications/reports/2018/gc63-5.pdf ↩

- For more on the challenges posed by environmental and structural factors at Yongbyon, see https://beyondparallel.csis.org/enhancing-understanding-of-yongbyon-through-thermal-imagery-part-3/. ↩

- Kevin Liptak and Jeremy Diamond, “‘Sometimes you have to walk’: Trump leaves Hanoi with no deal,” CNN, February 28, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/02/27/politics/donald-trump-kim-jong-un-vietnam-summit/index.html. ↩

- International Atomic Energy Agency, “Application of Safeguards in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” GOV/2019/33-GC(63)/20, August 19, 2019, 4, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gc/gc63-20.pdf. ↩

- Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. and Victor Cha, “North Korean WMD Facilities Idle Pre-Trump-Kim Summit,” Beyond Parallel, February 26, 2019, https://beyondparallel.csis.org/a-survey-of-major-north-korean-wmd-facilities-before-trump-kim-summit/. ↩

- United Nations Security Council, “Report of the Panel of Experts Established Pursuant to Resolution 1874 (2009),” S/2019/171, March 5, 2019, 65, https://www.undocs.org/S/2019/171. ↩

- International Atomic Energy Agency, “Application of Safeguards in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” GOV/2019/33-GC(63)/20, August 19, 2019, 4, https://www.iaea.org/sites/default/files/gc/gc63-20.pdf; Soo-yeon Kim, “(2nd LD) N.K. apparently running uranium enrichment facilities normally at Yongbyon: Seoul spy agency,” Yonhap News Agency, March 7, 2019, https://en.yna.co.kr/view/AEN20190307002352315?section=search. ↩