No Laughing Matter: North Koreans’ Discontent and Daring Jokes

A View Inside North Korea

Key Findings

- The second in our five-part series looks at how North Koreans think and talk about the government in non-public spaces.

- In private, almost all North Korean respondents know of complaints about the regime.

- North Korean citizens also tell jokes critical of the regime in closed company.

- Criticism of the regime is a serious crime punishable by imprisonment or even death in North Korea.

Additional Reading

- The first in our five-part series “Meager Rations, Banned Markets and Growing Anger Toward Government.”

- The third in our five-part series “Information and Its Consequences in North Korea.”

- Commentary “Samples of Convenience: The Merits of Conducting Surveys Inside North Korea.”

- Commentary “Considerations of Risk and Methodology For North Korean Surveys.”

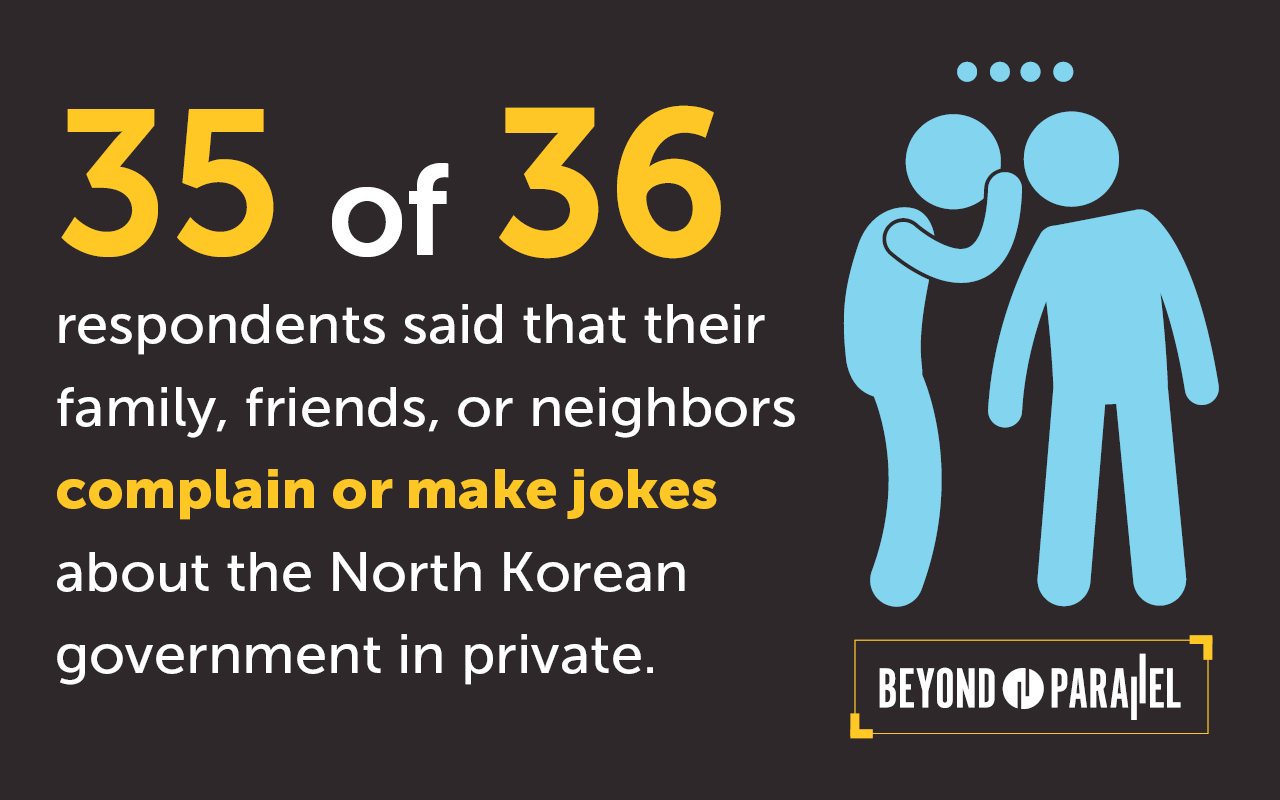

A Beyond Parallel descriptive interview project with North Koreans currently residing in North Korea found that 35 of 36 respondents’ family, friends, or neighbors complain or make jokes about the government in private. For the vast majority of the world’s population, especially for those people living in free and open societies, a similar finding would be quite banal. Political satire, jokes at the expenses of national leaders, and outright criticism of the government are normal parts of both public and private lives in democratically based states across the globe.

But North Korea is not a free and open society. That all but one of the Beyond Parallel interviewees say people they know complain and makes jokes about the government is an extraordinary number given the gravity with which the regime responds to criticism.

A Joke at Your Own Expense

The United Nations Human Rights Council established a Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the Democratic Peoples’ Republic of Korea to look into the situation of North Korean’s rights and freedoms. The Commission found that there is “an almost complete denial of the right to freedom of thought… as well as of the rights to freedom of opinion.”

In its February 2014 report the Commission wrote:

THE COMMISSION FINDS that there is an almost complete denial of the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, as well as of the rights to freedom of opinion, expression, information and association. … State surveillance permeates the private lives of all citizens to ensure that virtually no expression critical of the political system or of its leadership goes undetected. Citizens are punished for any “anti-State” activities or expressions of dissent. They are rewarded for reporting on fellow citizens suspected of committing such “crimes”. 1

People who express dissent or criticize the state, even if unintentionally, are subject to harsh punishments and detention, often punished without trial.2 Suspects of political crimes may simply disappear and their relatives may never be notified of the arrest, the charges, or the whereabouts of the alleged criminal. 3 If not executed, citizens accused of major political crimes are sent to a political prison camp, or 관리소. 4 In its 2015 survey of defectors from the DPRK, the Korea Institute for National Unification found that the majority of defectors stated the main reason for detention at a political prison camp was for critical comments and “misspeaking.” 5

No Inside Jokes

Even in private or among friends one assumes significant risk when joking or complaining about the government. The UN Commission found that the North Korean state had created a “vast surveillance apparatus” to monitor any expression of sentiments deemed anti-state or anti-revolutionary both through networks of secret informers as well as state organizations. Formal organizations such as the Neighborhood Watch (인민반) regularly monitor their members and membership in such a group is required for all North Korean citizens. Neighborhood watches are made up of about 20-40 households with a leader appointed to monitor the neighborhood for anti-state activities or dissent and to report to the authorities. 6

A Running Gag

A study by Seoul National University of North Korean defectors living in South Korea has consistently found the presence of some level of government criticism. From 2008 to 2015, the percentage of survey respondents who felt criticism was prevalent in a moderate to significant amount ranged from a low of 47.7% in 2014 to a high of 73.1% in 2012.

What sets apart the Beyond Parallel finding is that our respondents are still living in North Korea. One might expect to find defectors would be more aware of jokes and criticism of the government. They are, after all, the ones who decided to make the difficult and often dangerous decision to leave the country. One can therefore reasonably assume that defectors would have a more negative or critical disposition toward the government. However, the Beyond Parallel finding that the overwhelming majority of respondents still living in North Korea also make jokes at the government’s expense, is another thing altogether.

When you were living in the DPRK, how prevalent did you think criticism of the government (scribble, leaflet, etc) was in North Korea?

[1] The SNU study survey in 2008 and 2009 drew upon a pool of all North Korean defectors residing in South Korea. Starting in 2011 the survey covered only a pool of those who had arrived in South Korea during the previous year. No survey was conducted in 2010 to allow of the change in methodology.

Methodology

Given the gravity of the consequences faced for expressing opinions in North Korea, the methodology of the interview project commissioned by Beyond Parallel was designed to account for the current conditions in the country and protect all involved. In 2016, CSIS partnered with an organization that has a successful track record of conducting discrete and careful surveys in North Korea.

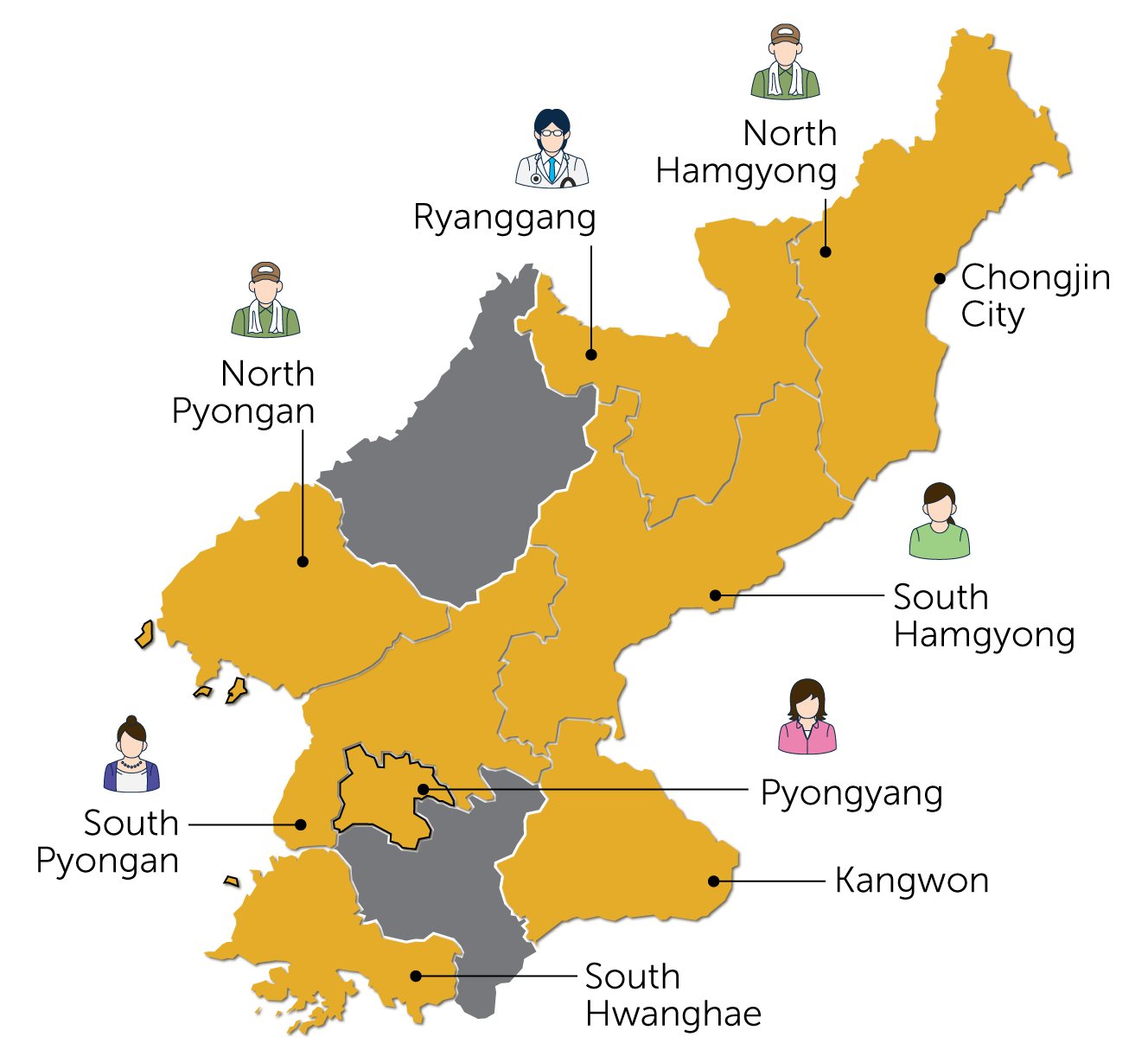

North Korea Survey: Sample Demographics

Beyond Parallel commissioned this organization to administer the questionnaire in eight provinces in North Korea. We talked with 36 men and women in walks of life ranging from laborers, doctors, homemakers, barbers, business presidents, to factory workers spanning in age from 28 to 80. The sampling method we used was non-probability, convenience sampling as accessibility was a prime consideration. There were no reported refusals to answer any of the questions posed by the administrators.

We began by asking North Koreans about the regime’s public distribution system, informal market and bartering activities, outside information, and unification. We inquired about events that drive their view of the government and foreign aid. The second in our five-part series focused on respondents’ answers to the following question: Do your family, friends, or neighbors complain or make jokes about the government in private? 이웃, 친구, 가족이 개인적으로 예전보다 국가나 삶에 대해 불평 및 비난을 합니까?

The questionnaire was carried out as natural in-person conversations between those conducting the interviews and the respondents. The individuals administering the questions are carefully trained to avoid asking leading questions or eliciting specific answers so as to protect both the integrity of the interview project and as well as safety of the people involved in the conversation.

The respondents were not cold-called by the administrators, but knew them in some fashion. This method is necessary in North Korea, where citizens’ concern is high that potential misunderstandings or misspoken sentiments with strangers could cause them to be reported to the authorities. Therefore, to gather the responses, the questions were discussed in natural and trusting settings with people who were somewhat but not necessarily deeply familiar with each other.

References

- UN Human Rights Council, Report of the detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, 7 February 2014, A/HRC/25/CRP.1, p.6. ↩

- U.S. Department of State, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea 2013 Human Rights Report, 2013, p.7. ↩

- UN Human Rights Council, Report of the detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, 7 February 2014, A/HRC/25/CRP.1, p. 210. ↩

- UN Human Rights Council, Report of the detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, 7 February 2014, A/HRC/25/CRP.1, p. 210. ↩

- Korea Institute for National Unification, White Paper on Human Rights in North Korea 2016, July 2016, p. 198. ↩

- UN Human Rights Council, Report of the detailed findings of the commission of inquiry on human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, 7 February 2014, A/HRC/25/CRP.1, p. 64. ↩