The Bunkers at Kyongje-dong

Key Findings

- CSIS Korea Chair satellite imagery analysis assesses that the Kyongje-dong facility is not associated with North Korea’s ballistic missile operating bases.

- The base lacks key identifiers of ballistic missile facilities such as drive-through facilities or barracks, given its size and layout. There here have been no notable changes to the facility since 2002.

- The Kyongje-dong facility was likely built to serve as a wartime forward operating base for MD-500s helicopters to support special force operations against South Korea during the early stages of a renewed conflict.

- Its location in the forward (or tactical) Scud belt has the additional benefit of allowing the MD-500’s 370 kilometers to reach further into the depths of South Korea.

- The construction timeline of the facility coincides with two pivotal events: 1) the construction of North Korea’s forward belt of Scud ballistic missile operating bases at Sakkanmol, Kal-gol, and Kumchon-ni and 2) the covert acquisition of 87 Hughes MD-500 helicopters.

- Like a number of air facilities in North Korea, the Kyongje-dong facility appears to be in wartime reserve or caretaker status.

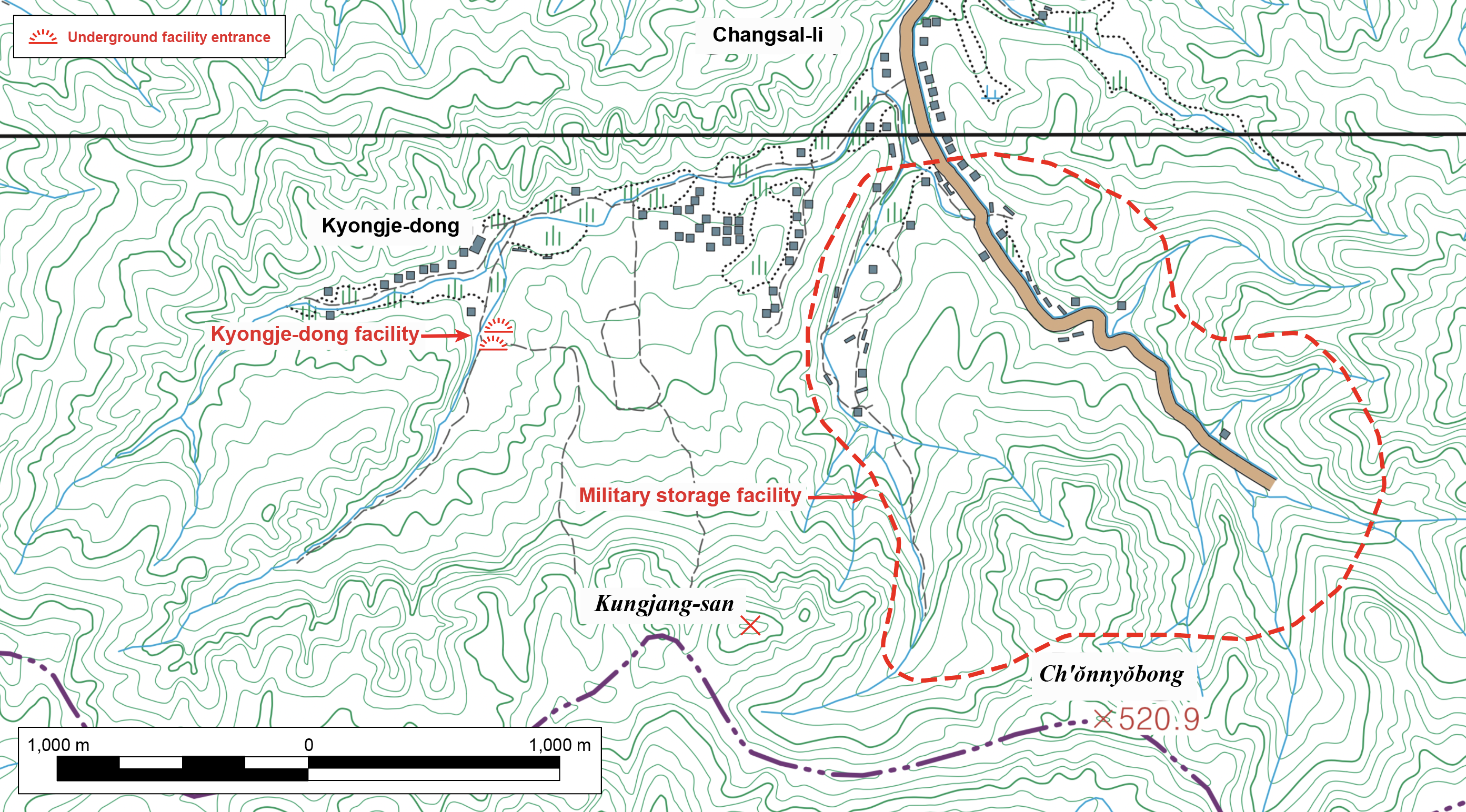

As noted in previous Korea Chair reports, the negation of information is often just as important as confirmation when studying North Korea’s ballistic missile and weapons of mass destruction infrastructure.1 Doing so focuses the public’s interest and policy discussions upon the facts that matter—real capabilities. Such is the case for the unique underground facility (UGF) located in an isolated valley on the northern slopes of Kungjang-san (궁장산, Kungjang Mountain) near the agricultural hamlet of Kyongje-dong (경제동), Yontan-gun (연탄군, Yontan County) approximately 17 kilometers northeast of the Sariwon-si (사리원시, Sariwon City), Hwanghae-bukto (황해북도, North Hwanghae Province) and 53 kilometers south-southeast of the capital city of Pyongyang-si (평양직할시).

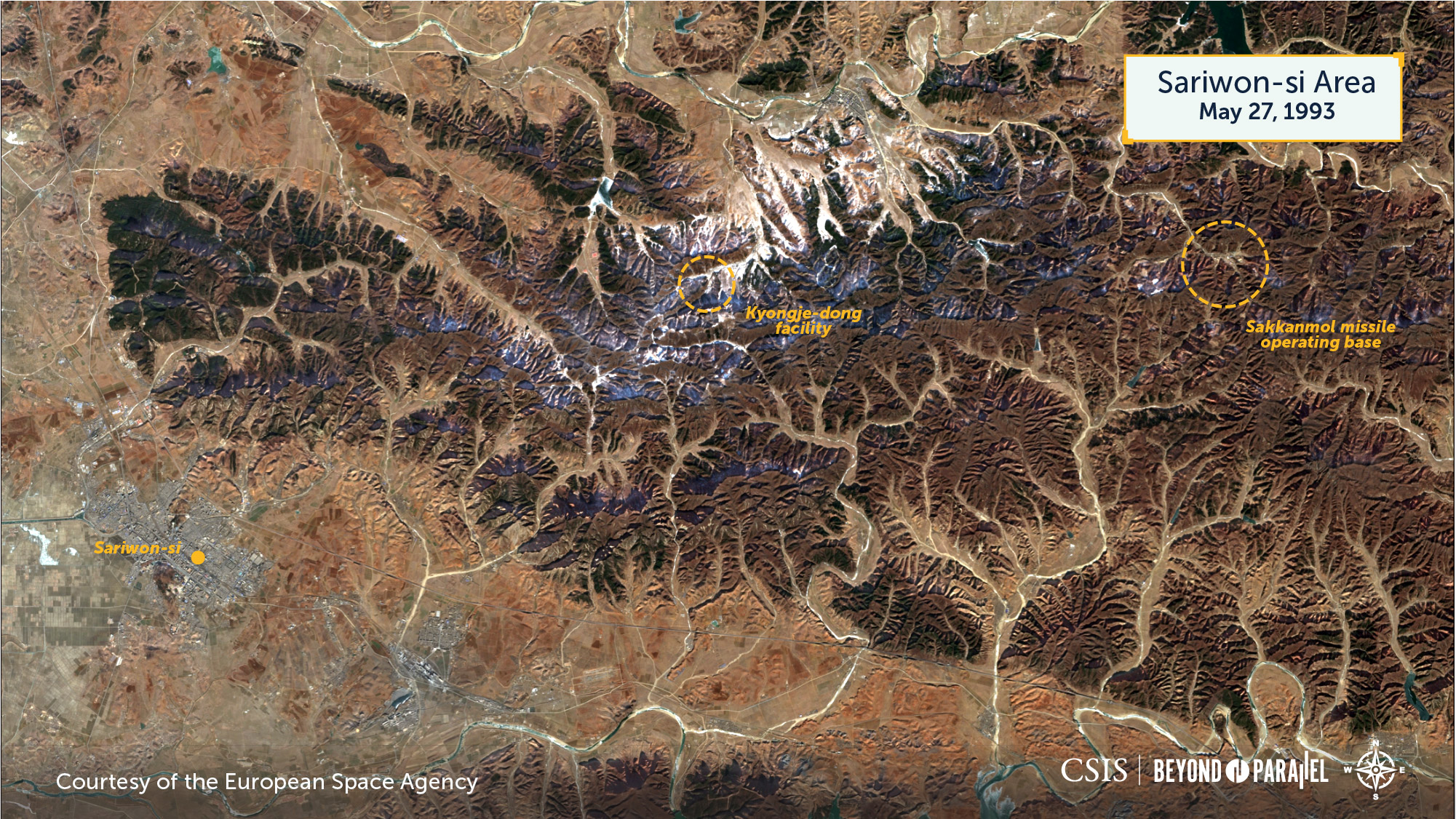

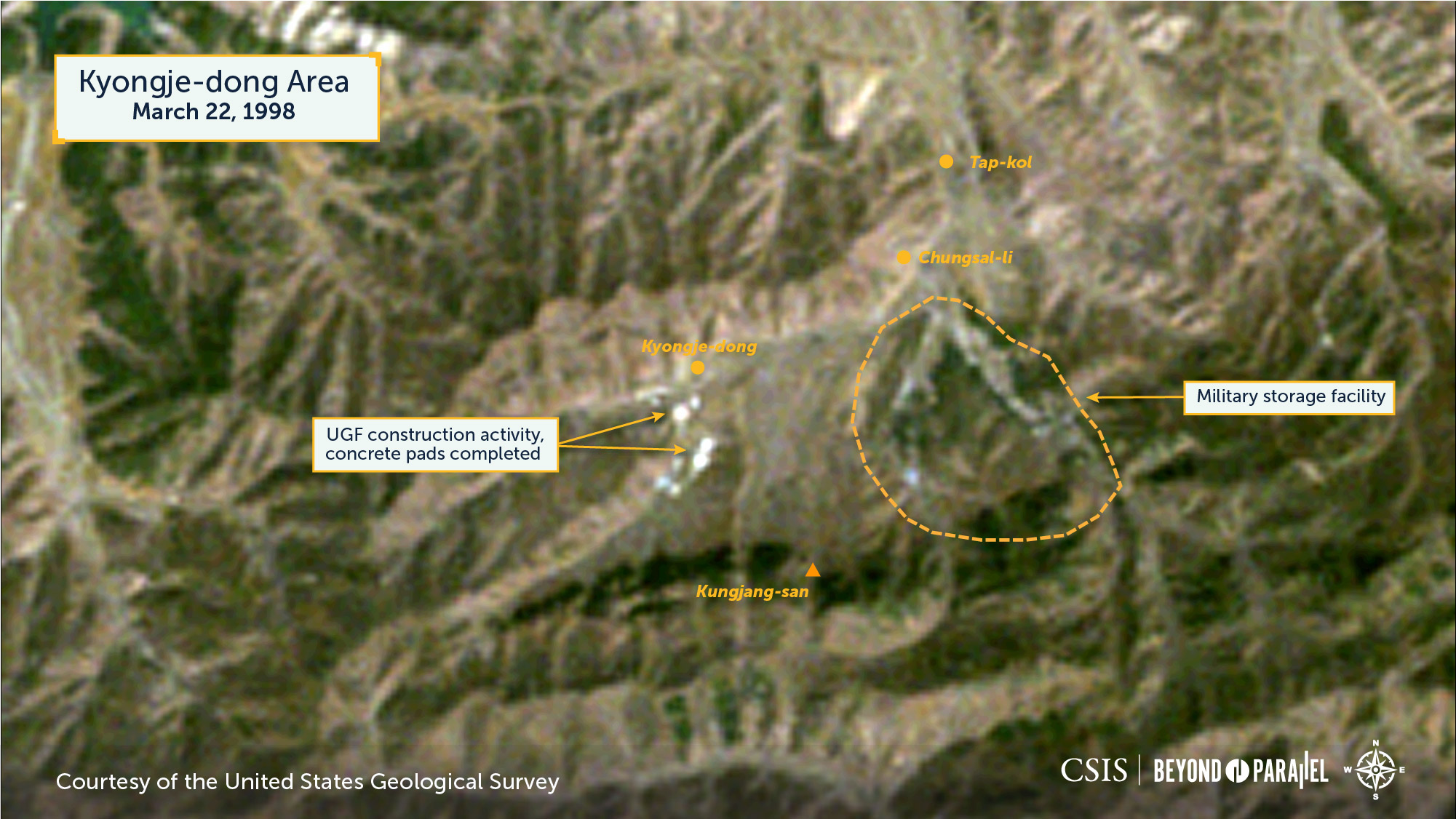

The precise construction timeline for the Kyongje-dong facility is unknown. However, medium-resolution Landsat 5 imagery suggests that ground survey and clearing may have begun as early as the late-1980s. Then, initial excavation began in about 1993, while the concrete pad in front of the northern entrance appears to have been completed during 1995. The second pad and facility were completed in about 1998.2 This Landsat imagery also suggests that the temporary structures—likely for construction workers—were built immediately around the Kyongje-dong facility and then subsequently razed when construction was completed.

This timing coincides with two pivotal events: 1) the construction of North Korea’s forward belt of Scud ballistic missile operating bases at Sakkanmol (삭간몰), Kal-gol (갈골), and Kumchon-ni (금천리) and 2) the covert acquisition of 87 Hughes MD-500 helicopters (see below). The former event was apparently the source of some early reports, which have sometimes been repeated in more recent years, of a ballistic missile operating base in the Sariwon-si area.3

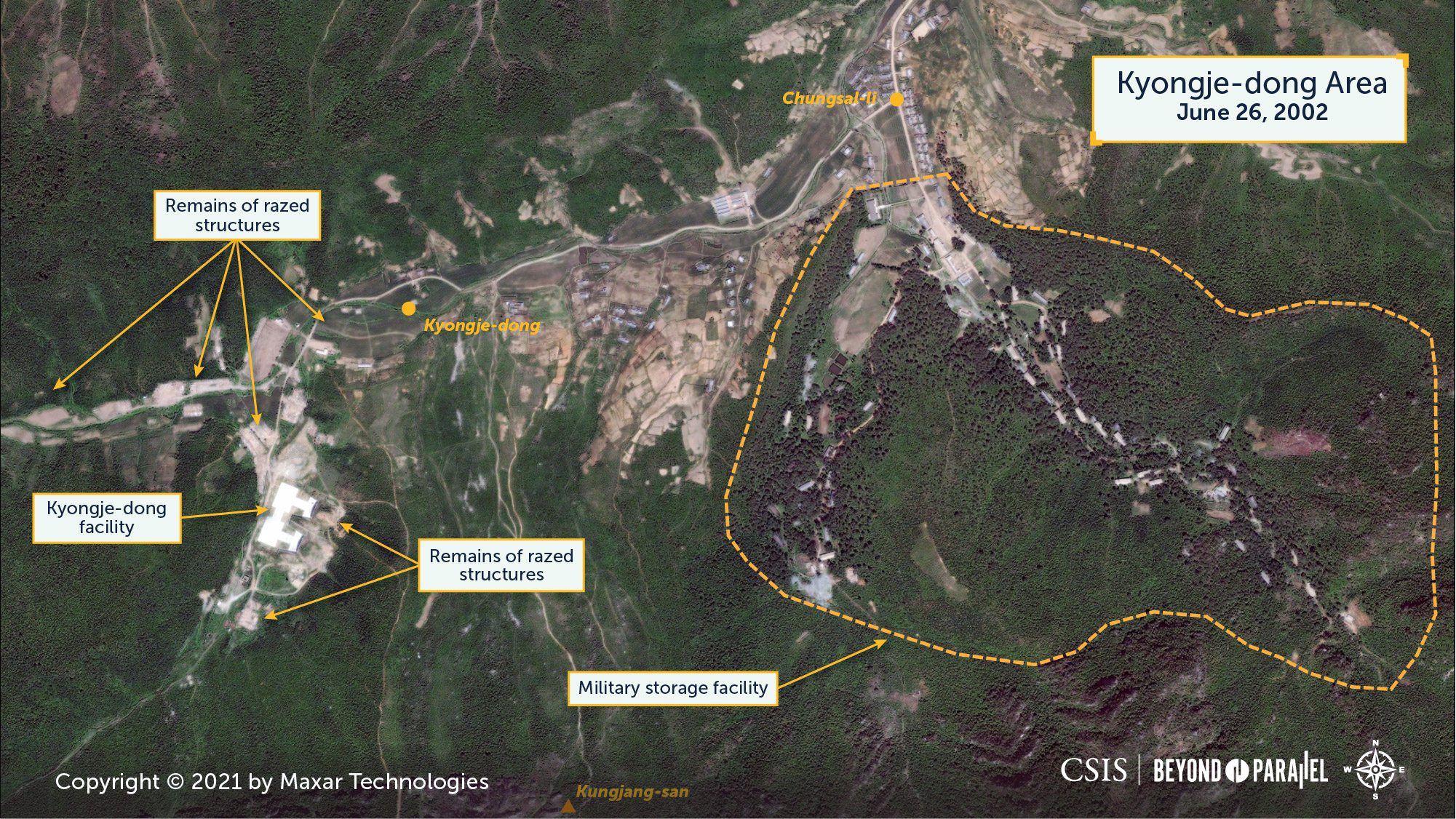

The first high-resolution commercial satellite image of the facility is from June 26, 2002. It shows that the small size, layout, and construction of the facility was not for a ballistic missile operating base, but rather for a unique fortified partially underground (PUG) facility—most likely intended for use by helicopters. This is not only indicated by the two large concrete pads in front of the UGF entrances, but also by the lack of any of the requisite above-ground support infrastructure (e.g., drive-through facilities, large barrack areas, motor vehicle storage, and maintenance facilities, etc.) to support a ballistic missile operating base or unit. In fact, the only military-significant activity observed in the general area of Kyongje-dong is the military storage facility at Chungsal-li (중산리) 1.5 kilometers to the east, which has been present in one form or another since the 1970s. This 2002 image also shows the likely remains of razed construction housing and support facilities used during the construction of the facility.

The Kyongje-dong facility consists of two large earth-covered concrete UGF entrances approximately 40-meters-wide, two large rectangular concrete pads measuring approximately 60-by-40-meters (larger than almost all helicopter pads in North Korea), and a small structure 100-meters north of the concrete pads, built during late-2004 to mid-2005. The latter likely houses a small local security or caretaker detail. The large UGF entrances are similar to those seen at some airbases with what appear to be segmented horizontal sliding doors. While the concrete pads are generally visible in most imagery, the UGF entrances are sometimes challenging to distinguish in summer satellite imagery given the growth of vegetation over the years and their location on the southeast side of the valley. Several small structures and ditches that are seen above the entrances since the early high-resolution imagery are likely related to air handling, communication, and/or electricity supply. Aside from the growth of vegetation above and around the UGF entrances, the area has not changed significantly since the June 26, 2002 image.

Numerous facilities within North Korea have large concrete pads or large associated UGFs. However, few have both that are also small in overall size, isolated, and possess such large UGF entrances. With regards to Korean People’s Air and Air Defense Force (KPAF) airbases, only a few have UGF entrances approaching the size of those at Kyongje-dong. No KPAF helicopter base or heliports, with the exception of the Sanghung-dong VIP Helicopter Base (상흥동) in the northern suburbs of Pyongyang, have associated hardened shelters or underground facilities. While the Sanghung-dong base is the closest analogue to the Kyongje-dong facility, it is not a strict match having two smaller 25-by-20-meters concrete pads and seven earth-covered concrete shelters rather an associated UGF with large entrances.4

Despite the indicators that the Kyongje-dong facility is intended for use by helicopters, no helicopters were observed in any of the 49 high-resolution commercial satellite images reviewed for this report. The only activities observed at the facility were the occasional presence of one or two vehicles and harvested grain being dried on the concrete pads. Like a number of air facilities in North Korea, the Kyongje-dong facility appears to be in wartime reserve or caretaker status.

Covert Acquisition of MD-500 Helicopters

During 1984-85, North Korea conducted a remarkable covert operation in which it acquired 87 Hughes MD-500 helicopters (20 Model 500Ds, 66 Model 500Es, and 1 Model 300C). These were civilian versions of the MD-500 defender antitank helicopters used in large numbers by the ROK Army. The KPAF subsequently armed many of these MD-500s and painted them in ROK Army markings.5 Thus configured, these helicopters have the potential to more easily penetrate South Korean airspace to deliver small teams of special operations forces on missions against high-value targets (e.g., airbases, THAAD bases, C4ISR facilities, etc.).

In 1986, the KPAF reportedly formed these helicopters into a special task force at Pukchang Air Base (북창) 70 kilometers north of Pyongyang.6 KPAF special operations force units have actively trained with these helicopters and have sometimes conducted this training near the DMZ—reportedly with occasional penetrations of ROK airspace.7 While the status of the KPAF’s fleet of MD-500 helicopters is unknown, several in camouflage with KPAF markings have appeared in North Korean reports and at the 2016 Wonsan Air Festival during the past ten years.8

Within this overall context, the Kyongje-dong facility was likely built to serve as a wartime forward operating base for MD-500s to support special force operations against South Korea during the early stages of a renewed conflict. This forward basing has the additional benefit of allowing the MD-500’s 370 kilometers to reach further into the depths of South Korea.

Research Note

Accuracy in any open discussion of North Korea’s ballistic missile programs is always challenging, and while some of the information used in the preparation of this study may eventually prove to be incomplete or incorrect, it is hoped that it provides a new and unique look into the subject.

Although 49 high- and medium-resolution satellite images were analyzed during the preparation of this report, the small number of images ultimately presented in this report were purposely selected for their detailed or historical view of the structures and activities within and around the Kyongje-dong facility.

Gazetteer of Named Places

| Name | Coordinates |

| Chungsal-li (중산리) | 38.583333 125.950000 |

| Kal-gol (갈골) Missile Operating Base | 38.670000 126.733611 |

| Kumchon-ni (금천리) Missile Operating Base | 38.964230 127.593302 |

| Kungjang-san (궁장산) | 38.569841 125.946477 |

| Kyongje-dong (경제동) | 38.578718 125.932490 |

| Kyongje-dong (경제동) Helicopter Base PUG | 38.577500 125.934551 |

| Pyongyang-si (평양직할시) | 39.083333 125.833333 |

| Pukchang (북창) Air Base | 39.504483 125.964637 |

| Sakkanmol (삭간몰) Missile Operating Base | 38.571925 126.114191 |

| Sanghung-dong (상흥동) VIP Helicopter Base | 39.064444 125.735556 |

| Sariwon-si (사리원시) | 38.524167 125.754722 |

References

- “Unique Facility in the Sanum-dong-Namgung-ni Area,” Beyond Parallel, January 14, 2020, coauthored with Victor Cha, https://beyondparallel.csis.org/unique-facility-in-the-sanum-dong-namgung-ni-area/. ↩

- The precise timing of the construction timeline of the Kyongje-dong facility will likely have to wait until additional high-resolution imagery is declassified. Among the more relevant Landsat images used for this report are: LT05_L1TP_116033_19900309_20170131_01_T1, LT05_L1TP_116033_19920922_20170121_01_T1, LT05_L1TP_117033_19930527_20170118_01_T1, LT05_L1TP_117033_19930308_20170120_01_T1, LT05_L1TP_117033_19950922_20170106_01_T1 and LT05_L1TP_117033_19980322_20161226_01_T1. ↩

- Author interview data. While there has been reports and speculation concerning a ballistic missile operating base in the Sariwŏn-si area during the early 1990s, the majority of these were general in nature, apparent misrepresentations to the Sakkanmol base (31 kilometers east of Kyongje-dong) or simply incorrect. To date, no authoritative data has come to light identifying a Scud missile operating base in the area. ↩

- Although these hardened shelters are built into a hillside, early satellite imagery does not indicate that they are connected to an underground facility. ↩

- Bermudez Jr., Joseph S. North Korean Special Forces—Second Edition, (Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute Press), November 1997, pp. 189; and “North Military Personnel, Arms Double in Decade,” Korea Herald, 27 July 1985, pp. 1-2. ↩

- Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.; and “Special Force Formed in DPRK With U.S. Helicopters,” Kyonghyang Sinmun, 24 March 1986, p. 1. ↩

- Interview data acquired by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr.; Defense Intelligence Agency, DIAM 57-25-112, February 28, 1985, p. 86; and Anderson, Jack. “N. Korea Penetrates S. Korean Airspace with U.S. Choppers,” Newsday, April 29, 1985, p. 54. ↩

- “Kim Jong Un Guides Combat Drill of Special Operation Battalion of KPA Unit 525,” Rodong Sinmun, December 12, 2016. ↩